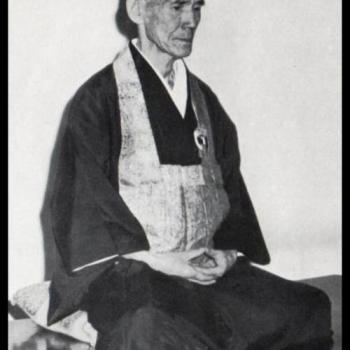

I’ll get right to the point here – if you buy one Zen book this year, this would be my strong recommendation. Harada Tangen Rōshi (1924-2018) was one of the few truly great Zen masters that I’ve met. Meeting Roshi-sama, as he is called by his students, and training with him at Bukkokuji, changed my life and practice in profound ways that still reverberate today, thirty years later. When my winding path intersected with Roshi-sama in the fall of 1990,... Read more