Here, in the Northern Hemisphere, it is Autumn. The days are getting shorter, the nights longer. It is also getting colder and wetter with each passing day, the leaves are turning shades of golden yellow, orange and red – and dropping. I have just harvested all the apples, pears and winter pumpkins and now all that remains is to clear away the debris of the gardening year that has been into the compost bins, where it can rot and return to earth again in due course.

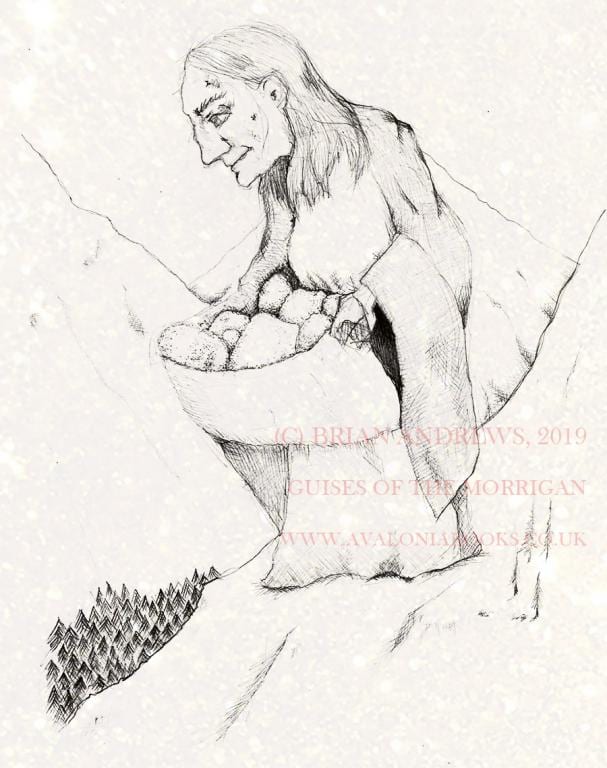

As Pagans our minds shift to the Gods of the Earth, the Gods of Death and of the Underworld, and the Gods of Snow and Ice. In Scotland and Ireland, but also other parts of the British Isles, this is the time of the Cailleach. She is the Crone of Winter whose stories were passed down through folklore and myth, and who may once have been a primordial Winter Goddess.

The Cailleach is intricately linked to this time of the year. Her story is that of the changing seasons in our landscape and though it is often overlooked in favour of Hellenic and other European myths, it is worth remembering that her stories are specifically linked to the Wheel of the Year festivals. She may not have been mentioned by Gardner and Nichols in their festival cycles, but she certainly is relevant to include if you are specifically looking to explore the natural cycles of this part of the world through the stories of the Gods and spirits who reside here.

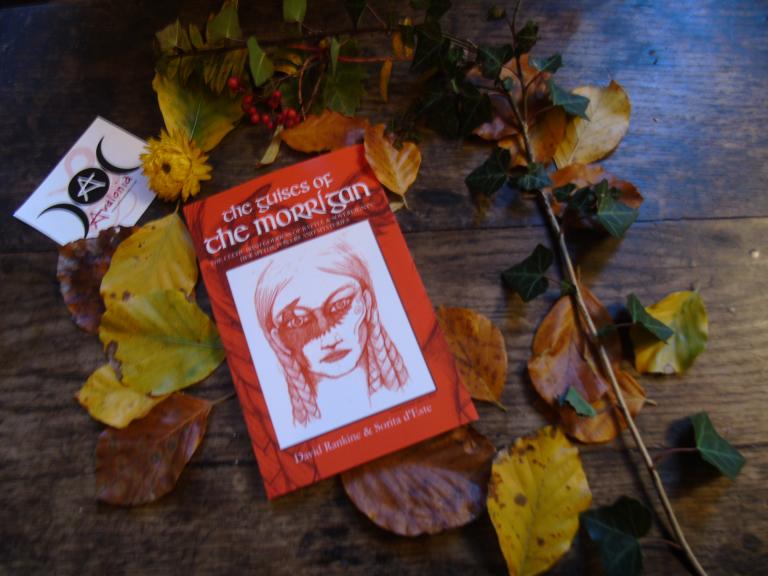

In the book The Guises of the Morrigan, which I co-authored with David Rankine (2005) we mention the Cailleach as the Winter Goddess. In 2009 we also compiled a small volume, Visions of the Cailleach, collecting the stories of the Cailleach from a range of folkloric sources. I hope you find it interesting!

Winter goddess

In one account the Cailleach is reborn on every All Hallows Eve (31st of October, the pagan festival of Samhain) as the winter goddess returning to bring the winter and the snows. She carries a magical staff which freezes the ground wherever she taps it.

At the end of winter, the Cailleach returns herself to the earth by turning to stone on Beltane Eve (April 30th with Beltane being on May 1st). The stone she turned into was said to remain “always moist”.[1] Before turning to stone, she would throw her magic staff under a holly tree or gorse bush, which are her sacred plants. A local verse provides an explanation, linking the action to the barren area usually found under holly trees:

“She threw it beneath the hard holly tree, where grass or hair has never grown.”[2]

In another legend, the Cailleach ushers in winter by washing her gigantic plaid (tartan cloth, usually worn over the shoulder) in the Corryvreckan whirlpool. This whirlpool near Jura and Scarba off the west coast of Scotland, and is also known as the Cauldron of the Plaid and the Cauldron of the Speckled Seas.

“Before the washing the roar of a coming tempest is heard by people on the coast for a distance of twenty miles, and for a period of three days before the cauldron boils. When the washing is over the plaid of old Scotland is virgin white.”[3]

The Cailleach is described as Gentle Annie[4] by the sailors of Cromarty in their efforts to appease her. The sudden storms which blow up there are considered to be caused by the Cailleach playing tricks with the weather. She is referred to in 18thcentury records from Strathlachlan as The Old Wife of Thunder due to her ability to command the weather at her pleasure. In perhaps the most extreme example of this weather aspect, she descends from Lochlann in a dark cloud and throws down thunderbolts and lightning, setting Scotland’s forests on fire.[5]

Referred to as the daughter of Grianan or Grianaig (Little Sun) the Cailleach Bheurs’ association with the seasons is further emphasised. Little Sun was a term used for the winter season when the power of the Sun was diminished in comparison to summer, which was the Big Sun. Here we return to a time when there were only two seasons, summer and winter – rather than the convention of four seasons today.

Summer was seen as lasting from Beltane (May Day, May 1st) to Samhain (31st October) and winter from Samhain to Beltane. In Celtic mythologies, these times are considered to be liminal times of magic and not surprisingly many stories exist telling of how these two dates are times when the veils between the worlds are gossamer thin. Both Beltane and Samhain are considered to be times when the separation between the worlds of the living and the dead, and mankind and the other – including faeries, gods and the ancestors; are at their thinnest. This allows for the best occasions for direct communication. It is also a time when the faerie court moves between their summer and winter palaces.

Variants of the seasonal connection place the Cailleach as ruling between the equinoxes instead. In these accounts she assumes power at the Autumn Equinox (circa 21st or 22nd September) until Spring Equinox (circa 20th or 21st March). The equinoxes are the days of the year when the sun is in the sky for equal lengths of time, marking tipping points for the seasons. The equinoxes were critical dates for ancient religious cultures around the world, and together with the mid-points represented by the solstices of June and December, formed the basis for many ancient ritual calendars.

The 25th March was referred to as Latha na Caillich (Cailleach Day) and is now more often known as Lady Day. The same day marks the day in the Christian calendar when it is said that the archangel Gabriel visited the Virgin Mary to tell her that she will be the mother of the son of God.

[1] Scottish Folk Lore and Folk Life – Donald MacKenzie, 1935, p138.

[2] Witchcraft and Second Sight in the Scottish Highlands – J.G. Campbell, 1902, p254.

[3] Myth, Tradition and Story from Western Argyll – K.W. Grant, 1925, p8,

[4] Also see Black Annis.

[5] Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, Volume 26:277-9.

Further reading: