The Irish Morrigan and the Roman Diana are perhaps the best-known Faerie Queens in Britain and Ireland today. The stories of both these powerful female figures survived into myth and legend well beyond the height of their respective periods of worship in the past, allowing them to find their place again today in the hearts and hearths of Pagans all around the world today.

Stories of the Faerie Queens are often linked to the liminal times of Samhain and Beltane, Halloween and May Day. This is perhaps because their stories are linked to life and death, war and love, passing beyond the boundaries of the ordinary in every possible way.

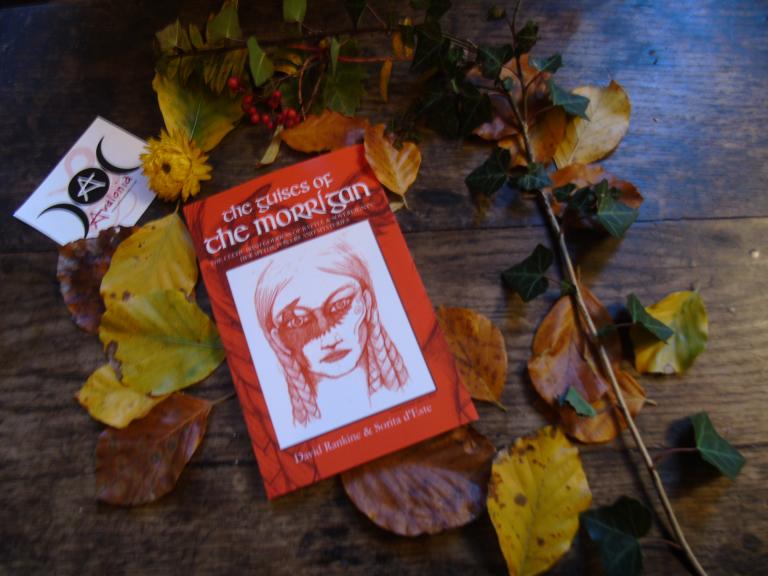

What follows is a short extract from the book The Guises of the Morrigan which I co-authored with David Rankine (2005).

The Faerie Queen

“Behold the chariot of the Fairy Queen!

Celestial coursers paw the unyielding air;

Their filmy pennons at her word they furl,

And stop obedient to the reins of light;

These the Queen of Spells drew in;

She spread a charm around the spot,

And, leaning graceful from the ethereal car,

Long did she gaze, and silently,

Upon the slumbering maid.” [1]

Rivers, fords, lakes, springs, and wells all play an essential part in Celtic myths. Votive offerings, in Celtic regions, were often deposited in bodies of water. Some of these offerings were carved and shaped to resemble body parts for healing (sympathetic magic), and at times such offerings would take the form of deliberately broken weapons or precious jewellery. The Morrígan is associated with a whole host of faerie beings across Britain and France. The best known of these faeries is probably the Banshee of Irish folklore. Sídh is often associated with the Morrígan in her various forms. It translates as faerie hill or faerie mound and is indicative of the connection between the goddess and the faerie beings. Landscape features such as mounds or burial chambers, and bodies of water, were considered to be entrances to the other worlds, including the worlds of faeries and the dead.

As Ireland became more Christianised, the old gods lost their public worshippers. Some of them were assimilated into the Christian pantheon becoming Saints (for example, the goddess Bride or Brigid became St Brigid) or they became demonised into malicious faerie and spirit beings. The term Túatha Dé Danann likewise became used as a generic term for the faerie folk, rather than as the name of a pantheon of deities. The Morrígan became the queen of the faerie Túatha Dé Danann, reinforcing the idea that Danu is another appearance of the Morrígan – or that these two goddesses became conflated.

Local folklore in Ireland asserts that the Morrígan leads the faerie court across the land at Samhain. This echoes traditions across Britain and Europe of the Wild Hunt being led across the land at this time of year by a significant god or spirit being. Other examples include the legends of Herne the Hunter and the Wild Hunt in Windsor and Gwyn ap Nudd and the Cwn Annwn (Hounds of the Underworld) between Wales and Glastonbury. Similar narratives can be seen in the germanic Dame Holda and the Wild Hunt; and in the legends of the Norse god Odin. The travelling faerie courts represent the power of the land shifting between summer and winter, and the powers of chaos being dominant at the times when the veils are thin. They are also able to traverse between the worlds of spirit and mankind.

As an aside, is worth noting that one of the Welsh terms for the faerie folk is Bendith y Mamau, meaning the Mother’s Blessing.

[1] From Queen Mab – Percy Blythe Shelley (1792–1822).