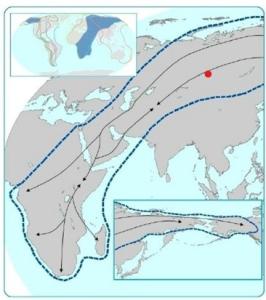

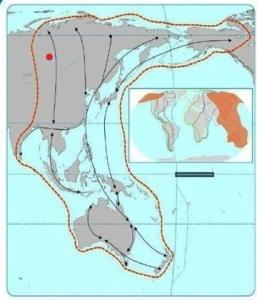

The fossil record and genetic evidence paints a clear picture of where our mysterious road-tripping cousins the Denisovans traveled, from Africa to Central Asia, the Tibetan Plateau and possibly Australia. Overlaying modern bird migration maps on the fossil record suggests the Denisovans followed avian migration routes around the world.

Since 2010, when fossil evidence was first discovered in Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Central Asia, Denisovans have emerged as a fascinating and very accomplished human-like species that may have survived in New Guinea until just 14,500 years ago.

The large size of fossilized molars suggests Denisovans were bigger than us, and bigger than Neanderthals. A 2019 genetic study at Hebrew University in Jerusalem concluded that Denisovans had wide hips like Neanderthals but their skulls were even wider and their jaws and teeth substantially bigger. Not enough is known to determine their height.

On the road with Denisovans

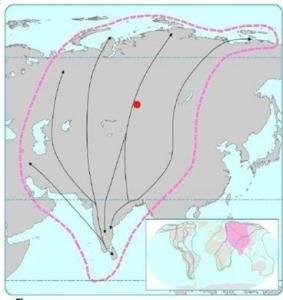

Denisovans displayed the very human trait of thriving in almost every environment on earth, including the forested mountains of Central Asia, the cold and dry climate of the Tibetan Plateau, the jungles of Southeast Asia and the tropical islands of Australasia. Geneticists now believe they were the first human species to cross the “Wallace Line,” meaning a viable population built boats and sailed east of Borneo to New Guinea and Australia.

More than 300 stone tools dating back 118,000 years on the island of Sulawesi, just east of Borneo, may have been Denisovan. Genetic evidence in the indigenous population suggests Denisovans also made it to the Philippines.

Up to five percent of the genome of people living today in Australia, the Solomon Islands, part of the Philippines and Papua New Guinea was inherited from Denisovans, considerably more than the 2.6 percent of DNA inherited from Neanderthals by western Europeans. But it was truly a surprise to discover that even Icelanders have Denisovan DNA, perhaps from archaic interbreeding in western Eurasia.

Clearly, Denisovans got around, probably inheriting their desire to hit the open road from Homo erectus, who made it to Asia long before the Denisovans. Geneticists suspect Denisovans in Asia met and interbred with a form of Homo erectus that had evolved there for millennia.

What inspired this desire to roam is a mystery of human nature, but how they did it could be partly answered by overlaying bird migration maps on the fossil and genetic “map” of Denisovan history. It appears they wisely followed bird migration routes, which never stray far from fresh water and abundant resources. Bird calls warn of predators and their mass-scattering behavior indicates extremely bad weather on the way.

The guidance of birds

Incredibly, a route of the East Asia/East Africa Global Bird Migration Flyway runs directly northeast in a nearly straight line from the Horn of Africa to Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains.

The only region in all of Europe and Asia where three global bird migration flyways converge runs from the Eurasian Steppes through the Altai Mountains to Mongolia (the global flyways are East Asia/East Africa, Central Asia and East Asia/Australasia). Three flyways converging is a rare occurrence across the globe that produces more than a thousand migratory bird species and a staggeringly high avian population.

Heading south from Denisova Cave are two routes on the Central Asia Global Bird Migration Flyway that lead to the Tibetan Plateau, where evidence of Denisovans dates back about 100,000 years. A 2014 study at the University of California concluded that Denisovans interbred with early Tibetans, passing on a hemoglobin-regulating gene that makes it easier to live at high altitudes.

Denisovan DNA was found in Baishiya Karst Cave in Tibet at an altitude of 10,500 feet – the cave opening offers a panoramic view of the landscape. A Lanzhou University study in 2020 found that Denisovans built fires in the cave about 100,000 years ago, again about 60,000 years ago and possibly for a third phase about 45,000 years ago.

Finally the East Asia/Australasia Global Bird Migration Flyways runs south from the Altai Mountains to Cambodia and Indonesia, but also connects to an east-west bird migration route that runs from Myanmar to Laos, Vietnam and the southern coast of China. This east-west route intersects with a north-south route that links to the Philippines and New Guinea.

In 2022, scholars in Laos announced what they believe is the discovery of another Denisovan molar, this one belonging to a young girl. The cave where the molar was found in northeast Laos is located on the east-running bird migration route.

Intercontinental sub-species intercourse

The odds of Denisovans officially becoming a new sub-species – Homo sapiens denisova – shot up when geneticists recently determined that both Homo sapiens sapiens (that’s us) and Homo neanderthalensis found their merry way to Denisova Cave and exchanged DNA with their larger cousins.

We can all thank these incredibly adventurous and apparently quite passionate early humans for the robust and diverse genetics that greatly benefit us today. Whether we like it or not humans are genetic mutts. And if all three human subspecies had never met and intermingled, pretty much all of human history would be dramatically different and very likely much less “successful.” Ask any geneticist.

Just a decade ago, many squeamish scholars argued that humans never interbred with Neanderthals. Now there’s conclusive evidence of interbreeding over a period of at least 30,000 years.

There’s no evidence of violence between the sub-species so far, only lots of sex, and geneticists continue to discover the true extent of the intercontinental romp.

Questions abound.

How exactly did the three sub-species meet? It’s a big world.

A 2013 study published in Current Anthropology estimated the total population of Neanderthals at any one time was between 5,000 and 70,000. Scholars estimate the population of early Homo sapiens sapiens may have reached 30,000, but dramatically dropped to as few as 1,000 about 70,000 years ago. No one has yet offered a reliable population estimate for Denisovans.

With three modest populations spread over the continents of Africa, Europe and Asia, how did they all end up having sex in Denisova Cave? Why didn’t they crush each others skulls with rocks? What was the attraction?

These days polarization over different shades of skin color and/or ethnic backgrounds and/or socio-economic classes can kill a romantic relationship before it starts – just ask Romeo and Juliet. How about bringing home a different sub-species with a super-wide face, a giant jaw and huge teeth!? Guess who’s coming to dinner!

The avian transportation network

These perplexing questions begin to resolve themselves if all three sub-species used the same transportation network of migratory bird routes. Recent studies have shown that bird feathers and talons were part of symbolic rituals held by Neanderthals around an egg-shaped stone ring. (For more on this, see previous column.)

If all three human sub-species crossed paths because of their shared belief in the wisdom of following birds, it would have been relatively easy to establish common ground. Maybe the Denisovans wore feathers in their dreadlocks while Neanderthals wore eagle-talon necklaces and humans donned swan-feather cloaks. Perhaps they all carried obsidian or quartz artifacts, gathered while following birds through their preferred volcanic habitats.

A 2013 study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology concluded that early humans developed language by imitating birdsong. Finding the FOXP2 gene in Neanderthals means they likely had a spoken language too, and the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics recently concluded that language may have emerged more than a million years ago.

Perhaps the languages spoken by all three sub-species were different but were all based in birdsong. There’s no video available of course and things like this can’t be proven one way or another, but the theoretical plot-line falls together nicely.

There’s just enough evidence to suggest the plausibility of birds being partly responsible, like a winged cherub with an arrow, for bringing together our far-flung ancestors in love and harmony, eventually producing our hybrid but robust genome. So keep those bird feeders full and your cat inside.

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: An Eco-History of Myth and Religion, coming March 2023 from John Hunt Publishing, now available for pre-order. More information can be found at this website, which links to a YouTube video.)