Welcome to another episode of “The Most Religious Thing”. We learned in our last episode that “Popcorn Popping” is the most genuinely religious song in the LDS-Mormon repertoire. Today, we’ll discover that The Book of Mormon is not only the most genuinely religious Broadway musical ever, but, perhaps, the most correct of any musical on earth.

This is old news. But I saw the show, again, last week.

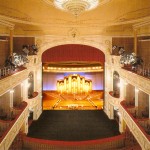

For those not in the know, Trey Parker’s, Matt Stone’s, and Robert Lopez’s musical opened on Broadway five years ago, earned a boxful of Tony awards and a crateful of money, and now has a number of touring productions so that you can see it where you live if you have a crateful of money to spend on such things.

Wikipedia describes the production as “a religious satire musical”, which seems to suggest that the play satirizes religion. Satire, it is. Parker and Stone have proven themselves to be about the sharpest, most canny satirists of our time. But I would recommend that we read Wikipedia’s description with a comma: “a religious, satire play”. Parker, Stone, and Lopez have offered up a critique of human behavior that ends up validating religion’s—even Mormon religion’s—best elements.

Puritanical critics of the play harp on such things as Brigham Young’s clitoris-nose and Joseph Smith’s untoward relationship with a frog, as though the saying of such things grievously wounds the universe. I would point out that even if sacrilege is an immanent, material danger to any exposed to it, a clitoris-nose is too wholly preposterous to be sacrilegious.

Harping on the grotesque hyperbole of scrotum maggots, etc., prevents seeing what the play so gleefully tries to do. Whether you’re for or against Mormonism, for or against religion, presuming that this play deliberately degrades religion by characterizing the LDS message as “stupid shit” is to willfully ignore the play’s rather not-very-subtle affirmation of both religion and the LDS version of it.

Consider the transformation of the play’s LDS missionaries. Collectively, gruesomely, naive, these doggedly chipper boys from the Mountain States start out singing “God loves Mormons and he wants some more!” and proceed to overrun and to run over a fictional Ugandan village coping as best it can with the not-very-fictional problems of poverty, war, and disease. By the end, the missionaries have surrendered their maniacal attachment to a book as well as their slavering commitment to a badly-behaving institutional authority. In the end, rather than continuing in the anti-social pursuit of minting new devotees to badly behaving institutional authority, the missionaries have taken up a new commitment to—as the play says—”helping people out”.

“We can,” exults Elder Price, immediately after giving his mission president the verbal finger, “work together to make THIS our paradise planet.”

I AM A LATTER-DAY SAINT

I HELP ALL THOSE I CAN

Price sings, and then all the rebel missionaries, together:

TOMORROW IS A LATTER DAY!

LOVE AND JOY AND ALL THE

THINGS THAT MATTER DAY!

And they affirm the book and its truth with new verve as “something incredible”, something that can, indeed, change lives through its demonstration of just how powerfully imagination can dispel the hopelessness that props up evil.

Here we have a “message play” with a worthwhile message, for once. The strength and value of religion—even of Mormon religion—is not in a historical or existential “factuality”. Indeed, as the rising generation’s dramatic slide into non-religiosity indicates, “factuality”, as such, may be religion’s worst feature. When the legitimacy of “factuality” can only be sustained by dogmatic insistence, religion only causes misery from which people flee.

But, as Parker, Stone, and Lopez assert, religion’s amenability to imagination means that religion has a remarkable capacity to inspire people to good ends. I’ve said it elsewhere: religion, like poetry, like painting, like music—even like math when math is imagining up things like √-1—does not tell us what we must think, but, rather, shows us what we can think.

While LDS folks fret and stew that this play’s mission president is a triple-a bunghole and shriek that—to cite a line—the play brings ridicule down onto the Latter-Day Saints (sic), they ignore that the play gives us a cohort of pathetic, spineless, miserable young men whose ignorance threatens everyone around them, but whose discovery of pure religion and undefiled turns them into selfless, Jesus-like, and joyful servants.

That conclusion constitutes the most religious Broadway musical of recent times. Maybe, ever. And it certainly reaffirms the genuine LDS-Mormon message that people exist to have joy.

The play’s assertion that the essence of religion is whatever inspires joy is so clear, so forceful, and so right, that we might well say of this The Book of Mormon what has been said of the other:

“A person will get nearer to God by abiding by its precepts, than by any other book.”

——————————

*Image from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Book_of_Mormon_@_Eugene_ONeill_Theatre_on_Broadway.jpg