[Editor’s Note: Please welcome Nicholas Laccetti to the Agora. Nicholas’s column, The Blooming Staff, will be published occasionally — but hopefully bimonthly. Subscription links are below. Welcome, Nicholas!]

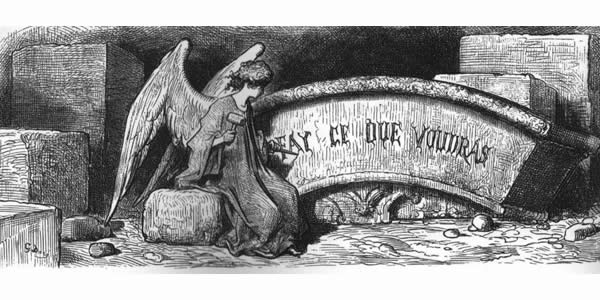

The priestess stands in front of the tomb, the symbolic equivalent of Malkuth on the Tree of Life. She proclaims: “By the power of Iron, I say unto thee, Arise. In the name of our Lord the Sun, and of our Lord [. . .] , that thou mayst administer the virtues to the Brethren!”

The priest emerges from the tomb. Osiris is risen. Osiris is risen indeed. But the Gnostic Mass is only just beginning.

The Gnostic Mass, the primary and public celebration of Ordo Templi Orientis, is one of Aleister Crowley’s supreme achievements in literary ritual. Just as the Mass of the Roman Catholic Church encapsulates the theology of Christ crucified and risen—according to Crowley, the primary expression of the previous Aeon of Osiris—the Gnostic Mass serves as a theological compendium of Crowley’s Aeon of Horus, the new spiritual era supposedly ushered in by his reception of the Book of the Law with his wife Rose in Cairo in 1904.

As a recent Master of Divinity graduate of a progressive Christian seminary, it might seem odd that I have attended an occult ritual Mass held by the heirs of the self-styled Great Beast, whose channeled holy book includes the quote, “I peck at the eyes of Jesus as he hangs upon the cross.” Crowley has been called many things: drug fiend, Satanist, egomaniac, and misogynist. When I told my mom I attended the Gnostic Mass for the first time, she asked me if it was a Black Mass. (I asked her if she knew what a Black Mass actually was. She did not.)

But in fact, Aleister Crowley, and his philosophy of Thelema, was the very first religious current that I had ever consciously explored—as a confused teenager reading a copy of 777 from a Long Island Barnes & Noble. It’s possible that the table of correspondences in that esoteric volume, which aligns Qabalistic, mythological, astrological, and Tarot symbols with corresponding colors, numbers, gods, stones and perfumes, profoundly affected my later scholarly concentration in religious studies. Or, perhaps it only amplified my preexisting synesthesia, or contributed to a tendency toward seeking paranoid meaning in everyday occurrences.

Whatever the case, my practice and study of Christian theology—specifically in its Anglo-Catholic and Roman Catholic forms—came later, in college and graduate school. I was baptized Episcopalian in my late teens because it was the closest thing to Catholic without excluding LGBT people, and later confirmed Roman Catholic in part to reconnect with my Italian-American roots. Various forms of radical Catholic theology and popular religion became my main focus by the time I found myself in divinity school.

During school semesters and in class, I would focus on mainstream, though progressive, forms of Christian theology. But during summer breaks, January intercessions, and the odd long bus ride to North Carolina or plane ride to Cleveland, I would delve back into the occult. Aleister Crowley, A.E. Waite, Kenneth Grant, Andrew Chumbley. The Golden Dawn tradition and Thelema. Luciferian witchcraft.

This pattern of splitting my spiritual time went on for several years. But then my Masters’ thesis heralded a conjunction of the spheres. I wrote a theological reflection on various forms of popular religion which are usually considered deviant or superstitious by official church authorities. The framework for the thesis was a conversation between the concepts of the carnivalesque and grotesque realism of Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin, and the radical creation theology of Catholic theologian Edward Schillebeeckx.

In the thesis, I argued that practices like magical evocation, the veneration of saints (including unofficial saints like Santa Muerte), divination, spiritual healing, and the carnival itself were spontaneous reflections of what Schillebeeckx called the humanum—the glorified future human being we see now only in shadow. And these practices, irrupting as they do from the grassroots of human religious experience, revealed the humanum to be a grotesque one, following Bakhtin’s reading of Francois Rabelais. The human is open ended, material, bodily and fecund. It oozes, flows, and erupts, much like the strange and sometimes troubling religious practices I examined for the paper.

Theologically, I had moved to a place of respecting the resolute pluralism, even polytheism, of the world—I no longer believed in the beautifully solid medieval dogmatic theology that subordinated all religious expressions to the death and resurrection of Christ, and to the sacramental reiteration of that event. If anything, I now believed that any living High God must be a festive God, who delights in the religious variety and chaos of the world. And following Schillebeeckx, the Trinity for me was less about Father-Son-Holy Spirit, and more about a divine Spirit in-built in all the cosmos, irrupting both in nature and in human expressions—artistic, religious, and magical—into forms that reflected the image of the human, which is also the image of God. Jesus Christ is one of these images, but only one.

I didn’t make the connection between my use of Bakhtin’s Rabelais and Crowley’s Thelema, even though the influence of Rabelais (a Saint in Crowley’s Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica) is well known. But when I finally graduated from divinity school and flowed back into my usual occult study, I realized something—my thesis had taken me from a mostly traditional theology that reflected, in Crowley’s terms, the Aeon of Osiris (the dying and rising god, Osiris and Jesus Christ) to a theology that resembled Crowley’s Aeon of Horus much more than anything currently practiced by the Christian churches. I didn’t have to split myself spiritually anymore. I had somehow reached a synthesis of understanding.

After all, it was Crowley’s Book of the Law, not the Bible, which upheld the delightful plurality of creation—“every man and every woman is a star,” every point-experience forged through the interplay of Nuit (limitless space with no circumference) and Hadit (the infinitesimally small point) is its own star, with its own orbit and its own satellites, set in its own constellation of experiences.

And as Crowley writes in the Book of Lies, “That which causes us to create is our true father and mother; we create in our own image, which is theirs. / Let us create therefore without fear; for we can create nothing that is not GOD.” So the myriad religious expressions I wrote about in my thesis, long considered deviant or taboo by the official church, were in fact to be considered images of the humanum, which is in turn the image of God. Therefore we can create nothing that is not God.

Coming to this realization is a bit like the priest emerging from the tomb at the beginning of the Gnostic Mass. There is still a long way to the high altar. If I am being led to newly appreciate Crowley’s Aeon of Horus, there is a lot for me to unpack. What does this mean for my understanding of academic theology and scholarship? Of Christianity, radical and traditional? Of ethics and aesthetics and spiritual practice? In future columns, I hope to explore some of these questions.

There are other synchronicities, personal, ethical, and spiritual, that pushed me to finally visit my local OTO temple and participate in the Gnostic Mass, and to finally commit to a practical and theological exploration of Thelema. For now, however, the starting point is here, in my realization that the divine spirit, like the Thelemic Hadit—“the flame that burns in every heart of man, and in the core of every star”—is militant and active in all corners of creation, and that there is no need any longer to subsume all human artistic and religious expressions under the one symbol of a dying and rising god.

For as the second speaker of the Book of the Law proclaims, “Remember all ye that existence is pure joy; that all the sorrows are but as shadows; they pass & are done; but there is that which remains.”

—

If you enjoyed this article, check out my new personal blog, The Light Invisible, for more pieces on Christian esotericism.

Patheos Pagan on Facebook.

the Agora on Facebook

The Blooming Staff is published on bimonthly, but without a fixed schedule, here on the Agora; follow it via RSS or e-mail!

Please use the links to the right to keep on top of activities here on the Agora as well as across the entire Patheos Pagan channel.