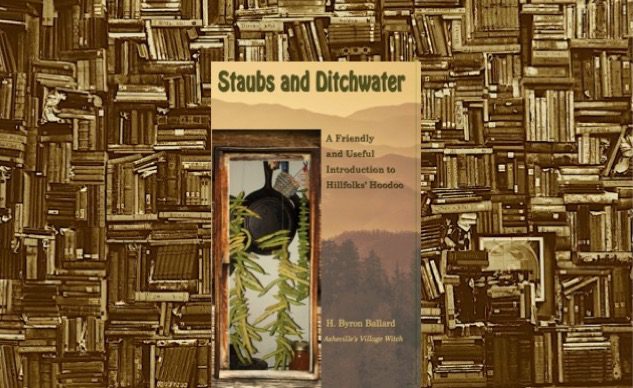

Staubs and Ditchwater is a compact paperback packed with wisdom born of life in Appalachia. Byron Ballard, who stylizes herself as “Asheville’s Village Witch,” is a rarity in modern American culture: she lives where her ancestors lived, going back generations. That’s allowed her to attune to her home in a way that few witches can, because the wisdom of those ancestors teaches lessons of that very same place. The result is a powerful sort of magic which comes through these pages, albeit not just through the precise words. What Ballard teaches in Staubs and Ditchwater is the hoodoo she learned growing up, and has mixed with techniques she’s developed or adapted from her years moving in Pagan circles. She intersperses chapters on the concepts and techniques with essays she’s written about her views and experiences.

The first of those is embedded in the introduction, and tackles the question of what she refers to as cultural strip mining, which is more colorful and precise phrase the cultural appropriation. Ballard is a white woman using a magical system typically associated with African Americans, but what she has come to call “hillfolk hoodoo” was given to her honestly, and race is not the specific focus of that essay. (Hoodoo and conjure are most likely an amalgam of practices brought from Africa on the slavers’ ships, traditions followed by eastern Native Americans before and during early European contact, and folk magic from Scotland and Ireland, together making a particularly American magical system.)

Rather, she struggles with a harsh reality: the traditions she knows are not being handed down through families any longer and might wither if not shared more widely, but yanking them out of their cultural context strips them of part of their power and robs those ancestors of proper credit. At the same time, it’s perfectly acceptable in her tradition to incorporate a “borry” learned from someone outside of it; that’s simply how human knowledge evolves. This a crossroads faced by root workers regardless of ethnicity or race. Ballard has opted to give her knowledge to the universe.

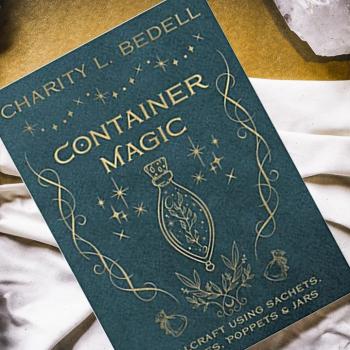

Between these covers can also be found details about the tools (one can never have too many canning jars) and materials (the list of different kinds of waters is particularly fascinating) used in hillfolk hoodoo , a chapter on divination and omen-reading (which includes not only the tarot familiar to many Pagans, but techniques ranging from tasseography to scrying in the clouds), and a passel of “receipts” (recipes) for specific spells. Readers are oriented to the vocabulary used in the hills, which provides a glimpse into the mindset of those who developed the techniques Ballard explains.

Quirks: one might finish this book feeling that there isn’t enough to start a practice, but anyone who thinks an esoteric tradition can be learned from a book alone is always mistaken. In this case, I’m certain Ballard could go on for several hundred more pages detailing exactly how she works, but this is a system based on what’s local. The herbs native to her part of North Carolina don’t entirely overlap with those growing in my more northerly part of the Appalachians, and likely not at all with those of the Great Plains. She provides some important basics and surely has more to offer, but the more advanced teachers must be the spirits of the land on which one lives.

Quibbles: there are inconsistent uses of capital letters throughout (psychic is sometimes capitalized, and deity more often than god), which just shows that Ballard shares in the common struggle over when to use the shift key. It also reflects how frequently today’s writers are not given the support of a professional editor, which everyone needs, because it’s a job quickly cut when budgets run tight.

Staubs and Ditchwater is a book worth reading not once, but multiple times. This is a volume which, if put to good use, will become as worn and stained as any trusted cookbook. Judge it not by its size, nor even by what is within it written; the wisdom comes through and will sinks into the reader’s unconscious if given the time and space. As Byron Ballard suggests in what she wrote in my signed copy, it’s about the work rather than the words: “Now you do the hoodoo.”