Commenting on my satirical post "Understanding Muslim Language", someone on an Internet discussion group shared an entertaining anecdote from Australia that illustrates one of the pitfalls of cross cultural translations in general and the literal translation of Muslim religious rhetoric into Western languages:

In Iran when you are frustrated with someone that you are talking to you say la ilaha illallah. Here in Australia they show Iranian movies rather frequently on a foreign language channel called SBS. In these movies they always translate this literally and I do love it when I am watching a movie with an Australian and he/she turns to me puzzled wondering why that man just spontaneously said ‘there is no god but God’ in the middle of a heated argument :^O

Of course, cross-cultural miscommunication and gaffes are endlessly entertaining, but I think ones concerning Islam such as this highlight an important concern, namely how difficult it is for relatively secularized Westerners to understand the significance of religious utterances by Muslims.

When you lack a background in a traditional religion and an experience of religion as being consciously at the center of one’s worldview, there’s a great risk of mistaking every innocent invocation of God and every natural manifestation of religious faith in a person’s life as religious extremism.

Religious Westerners who shudder at recordings of crowds in Muslim majority socieites chanting "God is Great!" should consider the from a traditional religious perspective very sad implications of the fact that Western street protestors are far more likely to invoke on "Freedom" or "Democracy" than God when making a moral argument today. I’m not sure that is an improvement.

Perhaps they need to read Richard John Neuhaus’ The Naked Public Square.

And then there are all the nuances that are difficult to ever grasp as an outsider to a religious tradition…

I was once speaking to a respected non-Muslim scholar of Islam. He, a very sympathetic observer with decades of experience among Muslims who had studied Arabic in the Middle East, made a error that was on the one hand entirely understandable but also inconceivable to most Muslims, even uneducated ones:

I gave him news of a mutual friend who was dieing of a painful condition and he exclaimed, "Oh, Masha’Allah, Masha’Allah!

Now, from a strictly lexical perspective this might seem appropriate, as the term after all means, "God has willed it" and Islam is of course the religion of "submission" to God’s will, but as anyone from a Muslim culture knows the phrase is in practice only reserved for good news or praise. What he clearly meant to say was Subhan Allah ("glory be to God"), which is what Muslims traditionally say upon hearing sad news. If one only judges by the literal meaning, "Masha’Allah" seems the more appropriate choice for such situations, yet cultural and religious practices in effect supercede its literal meaning.

One could also get into the differences between Al-Hamdulillah ("all praise is due to God") and Subhan Allah ("glory be to God"). On the face of it, they would appear to mean the same thing, yet they are also used quite differently situations and have different implications.

These examples are simple and perhaps even trivial, but if even they are not intuitive to a reasonably well informed observer, how much more confusion is likely to attend discussions of more challenging, variegated or even sharply contested ideas or practices?

Anyone have similiar experiences?

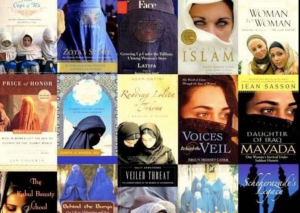

This is one of the reasons why in matters of religion I instinctively distrust accounts by outsiders. Whether it’s a Christian talking about Judaism–a long standing problem in Western intellectual life–or a Muslim holding forth on Hinduism. Of course, there are times when an outsider’s perspective casts new light, but I think more often than not that eye distorts and obscures more than it reveals.

Being an outsider does not ensure rigor, either. On thorny questions of theology, the reverse is sometimes true. Not only does successful interpretation require a large store of knowledge and experience that are difficult to acquire artificially from the outside, but adherents of a religious tradition are far more likely to make the intellectual effort required to make sense of confusing sets of facts due to their emotional investment in that tradition. For example, as a Muslim I have little need and thus motivation to look beneath the surface of Biblical accounts of Christ’s birth which appear at least from a surface reading to contradict one another. Rather than reflecting and researching these possible contradictions in an depth as a Christian might, I am more likely to take the path of least resistance (which in academic discussions of religion is often to "problematize") . I don’t need to get to the bottom of it, so I probably won’t.

In short, when traveling one needs a native guide, not an aloof, "objective" observer from the outside who even if proficient in the language is liable to fundamentally misunderstand local ways.

Of course, there are honorable exceptions to this rule and there is no question that outsiders sometimes bring new insights–e.g., amazing scholarship in Islamic Studies was done by those despised 19th century orientalists that Muslim and non-Muslim alike continue to benefit from today–but by and large I think it’s a wise motto to live by for people who are serious about seeking truth.

I’m reminded of a line from a Woody Allen movie. After telling somebody that he–a white and quite self-consciously Jewish man–was doing a PhD in African-American Studies, he quips, "Another few years and I’ll be Black!" For me that alludes to a fallacy many of us in academia unconsciously accept, that with enough study we transcend our backgrounds and become objective and no longer in need of native guides when we study other cultures.

It’s both noble and very important for people to interest themselves in other cultures, religions and ways of life, but the painful truth is that scholars who venture outside their own backgrounds must never

forget that like a person speaking a langauge other than their mother

tongue they are congenitally more at risk of errors both great and

small and therefore in need of regular validation of their assumptions

with the objects of their theorizing. Woody Allen will never become Black, whatever "Black" really is.