As a non-denominational evangelical Protestant I remember sitting in pew one morning while the pastor played a video created by a member of the church. It was a short, funny video made out of Lego dramatizing the appointment of Matthias from the Book of Acts.

The video followed the text from Acts but ended with a pithy, “…and he was never heard from again.”

We all laughed.

As evangelical Christians most of us, I would wager, had a fairly murky understanding of Church history. We laughed because all the fuss of appointing Matthias to replaced the disgraced and deceased Judas Iscariot is contrasted by the fact that, in the canon of the New Testament, he is simply never heard from again. All that work for nothing!

I learned later, when I began to dig into Church history, that there is in fact a long-standing, ancient tradition about what did happen to St. Matthias. It just isn’t contained in the New Testament. But Church history—historical documents—speak at great length about the replacement apostle and exactly what he got up to.

However, this is mostly besides the point. Because the appointment of Matthias to succeed Judas Iscariot is important not for what he did afterwards, who he was, or even why he was chosen but because he was chosen.

The importance of the whole procedure, along with three other important clues from the Acts of the Apostles, give us ample, concrete proof that the Early Church was Catholic. These proofs, from within the New Testament itself, should give pause to non-Catholic Christians or, in the least, beg some very profound and important questions.

If the Early Church was Catholic what does it mean for our faith today?

The Apostolic Succession of Matthias

The first clue that the Early Church was Catholic comes from, as I mentioned above, the appointment of Matthias to succeed Judas Iscariot.

Since Judas was handpicked by Christ his office as apostle, and the authority which came along with that, is really beyond dispute. I could quote chapter and verse to show how often Christ referred to the authority he was giving his apostles but I think this can be taken at face value: the apostles had a particular kind of authority.

So, when Judas betrayed Christ and hung himself from a tree that could’ve, you’d think, been the end of his authority.

The remaining apostles could’ve carried on as the eleven and gone out evangelizing the Jews and Gentiles in Jesus’ name.

But this isn’t what happened.

Importantly, the apostles see it as a given that they need to appoint a successor to Judas. So they go through a procedure imploring the Holy Spirit’s assistance and lay hands on a new apostle, a successor to Judas, to carry out the mission and mandate given by Christ.

Judas is replaced because the Early Church, the very apostles appointed by Christ, understood themselves to be operating in a kind of succession: if one falls, another is appointed. Their power and authority is duly and appropriately passed on from one man to another.

The apostles did not spread out amongst the Middle East and North Africa willy nilly but through an ordered, structured succession of leadership.

(Bonus example: Read how Paul describes Timothy’s authoritative succession as he sends him out to leadership as well. Even Paul appointed a successor.)

The question this begs, of course, is if the Early Church saw itself as an authoritative succession springing from Christ and carrying on, man to man, in an ordered way what about the Church today? The Catholic Church, tracing its lineage right back to Christ, maintains this remarkable succession. This is a fact of history, and pretty incredible, too.

But what about non-Christian Catholics?

The Authority of the Council of Jerusalem

The second clue to the Catholicity of the Early Church is what’s known as the Council of Jerusalem.

Arguably the first ecumenical Church council, here in the Book of Acts we see the apostles meeting to discuss opening up the Christian faith to the Gentiles for the first time—and what restrictions and boundaries should be place therein.

The meeting of the apostles, the discussion, and the decision making process doesn’t speak of a widespread network of random house churches. It doesn’t speak to a disparate group of believers spreading out amongst the Middle East and North Africa. It speaks to a highly organized and authoritatively structured body of believers—something that looks remarkably similar to the Catholic Church.

In fact, the Catholic Church exercises this exact same framework in its councils even today.

A framework which can be seen carried down through history ever since this very first Church council.

Subsequent Church councils laid out important theological concepts like the Trinity and even decided upon the canon of the Bible. Councils which traced their authority, directly, to the very first council.

The question this begs, of course, is if the Early Church held councils which had binding authority on all Christians—drawing boundaries lines of who could be in and who was out, in this important example—why doesn’t the Church still do the same thing today to decide on important contemporary issues like same-sex marriage and gender identity? Well, the Catholic Church still does. And councils, which have been held ever since this first one in Jerusalem, are something of authoritative substance to Catholics all over the world.

But what about non-Catholic Christians?

The Denial of Sola Scriptura

The third clue which reveals a distinctly Catholic Church in the New Testament is the decision which is made at the Council of Jerusalem in the Acts of the Apostles.

Not only was a council held, an act which looks distinctly Catholic in nature, but the decision is distinctly Catholic too.

Overtly so.

In fact, the decision to open up membership in the Church of Christ, to forego Gentile believers having to undergo circumcision, was a decision made in contradiction to what would’ve been written in the Hebrew Scriptures. Jews were told, since the Covenant of Abraham, that males needed to be circumsized. Likewise, restrictions were placed on what Jews could eat and come in contact with, etc. But the Council of Jerusalem, over and above those that argued for sticking with the Scriptures, decided against these time-honoured, Jewish practices.

No longer, said the apostles, did Christians have to obey the ancient laws of the Jewish faith. Christians, therefore, would not follow the Hebrew Scriptures alone but would establish a new, previously unwritten Tradition.

These first century Christians saw Christ as having established a living Tradition which wasn’t simply recorded in the Scriptures. Otherwise, they could’ve agreed, under the influence of the Holy Spirit, that yes, Christians should continue to practice this important sign of the Abrahamic Covenant. And not eat certain meats, too.

The decision, however, was a break from relying only on Scripture to inform how the first century Christians were meant to live.

This begs the question, of course, if the very first Christians saw themselves as able to develop new Tradition, led by the Holy Spirit, and not merely rely on what was written why would Christians suddenly argue that only what’s written in the Bible holds authority? Where does that idea come from? And who put together the Bible anyway?

On the other hand, the Catholic Church, since the Council of Jerusalem, saw itself as guided by the Holy Spirit in order to interpret, decide, and decree which Traditions should be practiced by Catholic Christians down through the history of the Church.

But what about non-Catholic Christians?

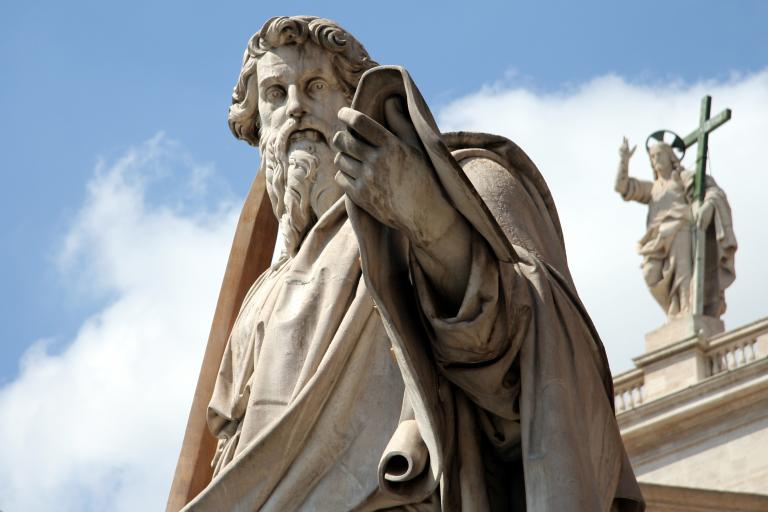

The Authority of Peter as the First Pope

Finally, the Acts of the Apostles gives us one more clue into the Catholic nature of the Early Church and this too comes from the Council of Jerusalem and its surrounding discussion.

Often non-Catholic apologists will point to Paul’s challenge of Peter in Acts as a kind of anti-apologetic for the papacy. Peter most certainly can’t be considered the first Pope because Paul challenges him to his face, corrects him even. The simple response is that Popes are not always right. Peter was backsliding by refusing to eat with Gentiles and Paul knew it; Paul corrected him to his face because he was wrong. Popes can be wrong—they can also be infallible but this is in very particular circumstances.

However, we see far more indications that Peter was considered first amongst the apostles and the leader of the Christian Church than we see to the contrary. While these examples are littered throughout the New Testament (and even the Old!) we’ll stick, for our sake, to the Acts of the Apostles.

And the Council of Jerusalem gives us a good clue.

Because after all the discussion, after all the back and forth, it is Peter who stands up to authoritatively proclaim the decision of the council—the opening up of the Christian faith to the Gentiles.

And what does Paul, for all of his disagreeing with Peter, call the first Pope? He refers to him as “Cephas,” which means “the Rock.”

It is, in fact, a title. An authority.

And while the idea of the papacy was certainly something that developed over time in the history of the Church there are clear as day indications that, even if it wouldn’t have been described as it is today, it was clearly understood. Even in the infant Church.

(Bonus example: the writings of the very earliest Church Fathers like St. Clement clearly demonstrate the primacy of what would come to be called the “chair of Peter.” When Peter died as leader of the Church in Rome, that particular “chair” in Rome took on a very important, primary role, in the Early Church.)

The clear authority of Peter, above all the other apostles and believers, begs the question of the importance of this particular apostle and the importance, going forward, of his role. The Early Church clearly understood this and the New Testament makes it clear. Did the authority of Peter as the chief apostle to authoritatively settle disputes about theology suddenly end when he died? The very first Christians certainly didn’t think so.

But what about non-Catholic Christians?

In the end, I think these are four excellent proofs for the Catholic Church in the Acts of the Apostles. Of course, as a non-denominational evangelical Protestant I would’ve never seen this as Catholic at all. I didn’t know what the Catholic Church was; I didn’t know what she taught and I certainly didn’t know my Church history very well.

When my eyes began to open up to the reality of the Church through history, to the continuity of the practices we can find all the way back in the New Testament, my worldview was completely shattered.

Once I realized that the Catholic Church can be convincingly found in the New Testament, and down through Church history, I could do nothing else.

And, like Peter said to Christ Himself, “Where else can I go?”