I have been trying to write this post for a week or so and I am still struggling with it. In my last post, I wrote about the ambivalent attitude I have about food, and how Neopagan myth has helped me to experience what Jane Ellen Harrison calls the “sacramental mystery of life and nutrition that is accomplished in us day by day”.

With that goal in mind, I have a prayer that I say before eating — when I remember, which I admit is rare — which helps me experience eating as a sacrament:

Gods are mortals,

Mortals are gods,

Living each other’s death,

Dying each other’s life.

To live the death of a being to eat it.

To die the life of a being is to be eaten.

We eat God,

And are devoured by Her.

The first part of this prayer is from the pre-Socratic philosopher, Heraclitus. I could write a whole post (or more) on Heraclitus alone, but I will restrict myself to the fragment above for now. Heraclitus was more of a poet and mystic than a philosopher. He is called the “Fire Priest” sometimes. His “philosophy” as it has come down to us in its fragmentary form is a collection of meditations on the unity of opposites in the form of paradoxical statements which resemble Zen koans.

The Greek of this fragment reads:

ἀθάνατοι θνητοί, θνητοὶ ἀθάντατοι, ζῶντες τὸν ἐκείνων θάνατον, τὸν δὲ ἐκείνων βίον τεθνεῶτες

Athanatoi thnetoi, thnetoi athanatoi, zontes ton ekeinan thanaton, ton de ekeinan bion tethneates.

The process of translation of this text is in itself a meditation on its paradoxical meaning. The literal translation is:

Immortals (the deathless) mortals (the dying), mortals immortals, living one another’s death, one another’s life dying.

This text is a meditation on the paradoxical unity of life and death, immortality and mortality, the gods and humankind.

The second part of my prayer is an exegesis on Heraclitus’ words by the philosopher, mystic, and activist, Simone Weil. A year and a half before her death, Simone Weil copied the fragment above from Heraclitus in a notebook along with the following commentary:

“To live the death of a being is to eat it. The reverse is to be eaten. Man eats God and is eaten by God”

(Complete Works VI.2., 454). The cause of Weil’s death is debated, but it is believed that, after a battle with tuberculosis, she starved herself to death.

So what does this mean? First, the prayer is a reminder that my life feeds on the death of other beings. I live by eating the flesh of slaughtered animals, grain which is cut down and ground to make bread, and the fruits that fall from the plants that grow in the earth. It is also a reminder that my death will feed the life of other beings when my body decomposes.

But there is more to it than that. And here is where I begin to encounter difficulty, because I am leaving the realm of my experience and entering the realm of speculation:

Through the process of eating and being eaten, other beings become a part of me, and I become a part of them. But this prayer also hints that, through the act of eating, we participate in something larger: the cycle of Life, God, the Goddess. Ruby Sara beautifully articulates this mystery at the blog No Unsacred Place:

“How remarkable that we can eat our god who then becomes us becoming Her becoming us.”

The idea that we become a part of God through sacramental eating is obviously familiar in a Christian culture. Possibly no better statement of this mystery can be found than in the Gospel of John:

Whoso eateth my flesh, and drinketh my blood, hath eternal life … For my flesh is meat indeed, and my blood is drink indeed. He that eateth my flesh, and drinketh my blood, dwelleth in me, and I in him.

While Christians struggle to explain the meaning of the Eucharist in terms of a the Neoplatonic philosophy or in terms of mere metaphor, as a Neopagan, I understand the god-man’s words literally. Our bodies are meat and our blood drink, for predators and parasites. And when I eat the flesh of other animals, they become a part of me. And when I die, I will become a part of other animals that will consume the flesh of my body. Thus, sacramental eating involves a conscious awareness of my own mortality. John Vickery, author of The Literary Impact of the Golden Bough, writes: “To recognize death and mortality and to live fully with that awareness is to know the only true idea of the holy available to man in this or any other century.”

But I think there is more to the mystery of sacramental eating than this. By recognizing my part in this cycle … no, by experiencing my part in this cycle, viscerally, through sacramental eating, I hope to begin to identify not just with those beings whom I consume consume and who will consume me one day as a part of the cycle of Life, but I hope to begin to identify with the cycle itself. In Neopagan terms, I hope that sacramental eating will help me to identify not just with the dying and reviving god who represents the manifest life of individual beings, but with the Goddess who is Life itself — Life with a capital “L”, Life in the sense that encompasses death as part of an eternal cycle.

Jule Cashford and Anne Baring describe the meaning of Life in this larger sense in terms the two Greek words for life: Zoe and bios. According to Cashford and Baring, ” Zoe is eternal and infinite life; bios is finite and individual life. Zoe is infinite ‘being’; bios is the living and dying manifestation of the eternal world in time.” Zoe is the whole; bios is the part. Bios is the manifest world, “the epiphany, or ‘showing forth’, of the unmanifest”, which is Zoe. And human, animal and plant life are all part of this epiphany. “Zoe is then both transcendent and immanent, and bios is the immanent form of zoe.”

(Interestingly, forms of both words, Zoe and bios, are used by Heraclitus in the fragment discussed above: Immortals mortals, mortals immortals, living [Zoe] one another’s death, one another’s life [bios] dying.)

In Neopagan myth, the relationship between Zoe and bios is personified in the Bronze Age myth of the Great Mother Goddess and her son-lover:

“[T]he Goddess may be understood as the eternal cycle of the whole: the unity of life and death as a single process. The young goddess or god is her mortal form in time, which, as manifested life […] is subject to a cyclical process of birth, flowering, decay, death and rebirth.”

The Mother Goddess is Zoe, “the eternal source, giving birth to the son as bios, the created life in time which lives and dies back into the source.” In this myth,

“the son-lover must accept death – as the image of incarnate being that falls back, like the seed, into the source – while the goddess, here the continuous principle of life, endures to bring forth new forms from the inexhaustible store.”

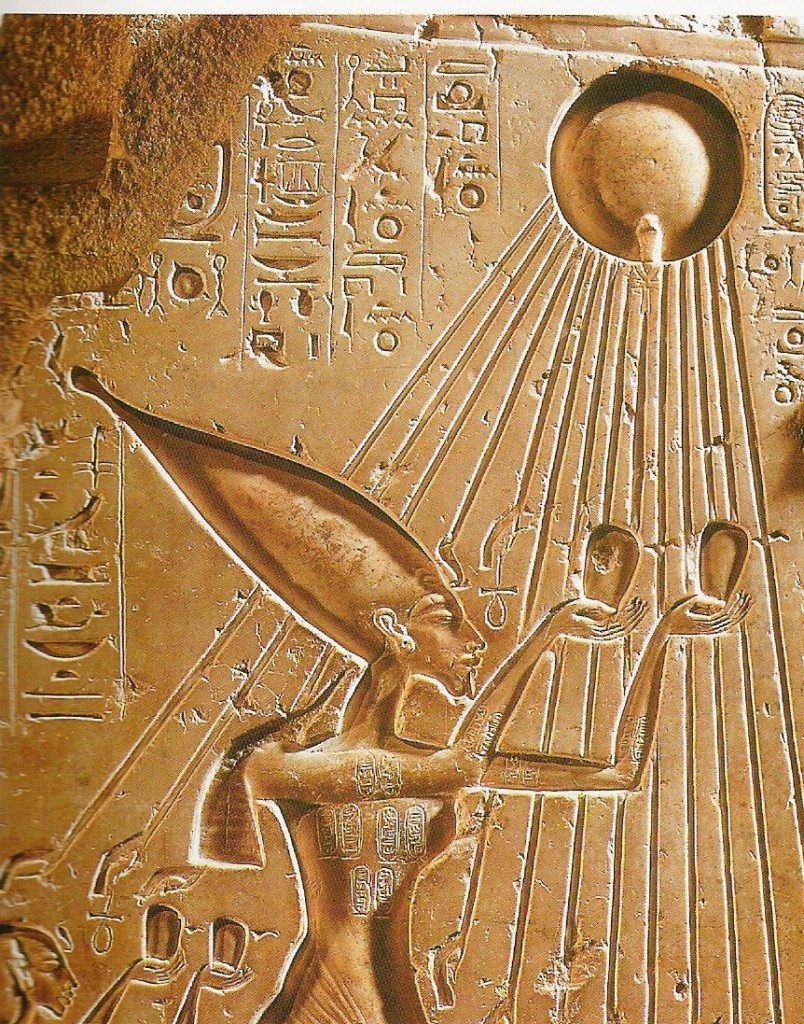

And this is the meaning behind the myth of the dying and reviving god. According to Margot Adler, the McFarland Dianics quote a phrase attributed to Bachofen to explain the relationship of the Goddess to her son-lover:

Immortal is Isis, mortal her husband [Osiris],

like the earthly creation he represents.

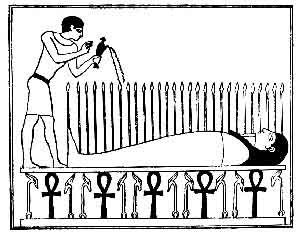

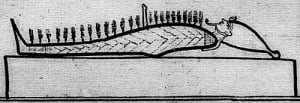

This idea of finding a new kind life through death was expressed in an ancient prayer found in the Egyptian Coffin Texts in which the deceased identifies with Osiris, the dying and reviving god of the grain. Spell 330 reads:

Whether I live or die I am Osiris,

I enter in and reappear through you,

I decay in you, I grow in you,

I fall down in you, I fall upon my side.

The gods are living in me,

for I live and grow in the corn (Nepry)

that sustains the Honoured Ones.

I cover the earth,

whether I live or die I am Barley.

I am not destroyed.

I have entered the Order (Ma’at),

I rely upon the Order,

I become Master of the Order,

I emerge in the Order,

I make my form distinct,

I am the Lord of the Granary of Memphis,

I have entered into the Order,

I have reached its limits.

In this spell, the deceased transcends his own death by identifying with grain, something which is eaten, by mortals and gods alike. The grain grows and falls, lives and dies; but the deceased lives on as part of Ma’at, which is translated here as “Order”. Ma’at was the Egyptian personification of order in the universe, including the regularity of the seasons, what Cashford and Baring call Zoe, the Great Mother Goddess.

As I understand it, the promise of “eternal life” by Jesus in the Gospel of John (above) is not the promise of an unending life [bios] of the individual ego-self, but the promise that we may become one with that Life [Zoe] which transcends the death of the individual ego. It is eternal, not in the sense of extending into infinity; it is eternal, rather, because of its cyclical nature.

Ironically, this Life eternal can only be experienced through death.

That which thou sowest is not quickened, except it die.

(Epistle to the Corinthians). Bachofen writes in his Motherright of the mystery of material nature which is manifest in

“the transformation of the seed grain and the reciprocal relation between perishing and coming into being, by which death is revealed as the indispensable forerunner of higher rebirth.”

But what is this death that is the indispensable forerunner of higher rebirth? It is not just the physical death of the body; it is also the death of the ego-self. Elsewhere, Simone Weil wrote:

“The beauty of the world is the entrance of the labyrinth. The imprudent person who, having entered, takes a few steps, is after some time unable to find his way back. … If he doesn’t lose courage, if he continues to walk, it is absolutely certain that he will arrive at the center of the labyrinth. And there, God is waiting for him, to eat him. Later, he will leave again, but changed, become other, having been eaten and digested by God.”

Weil was writing here about the death of the ego that occurs when we are “consumed” by the abyss which is God or the Goddess, when we “die” to our individual lives and are reborn to the Life eternal of the gods.

R. D. Laing writes, in The Politics of Experience, about ego-death in the context of his discussion of the close relationship of madness to mystical experience:

“True sanity entails in one way or another, the dissolution of the normal ego, that false self competently adjusted to our alienated social reality: the emergence of the ‘inner’ archetypal mediators of divine power, and through this death a rebirth, and the eventual re-establishment of a new kind of ego-functioning, the ego now being the servant of the divine, no longer its betrayer.”

The irony is that we might experience this dissolution of the ego, in some measure, through the act of eating, which is intended to perpetuate our individual lives. But by making eating into a sacrament, the meaning of the act is inverted: God eats me, and I become part of God. Maurice Friedman calls Wiel’s imagery “inverse cannibalism”, letting oneself be eaten: “the complete denial of the self in favor of the unlimited affirmation of the Other with whom the knowing self identifies itself” (emphasis original).

Interestingly, Joseph Campbell, in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, also uses the imagery of the labyrinth to describe the ego death experienced by the archetypal hero. He :

“We have not even to risk the adventure alone, for the heroes of all time have gone before us — the labyrinth is thoroughly known. We have only to follow the thread of the hero path, and where we had thought to find an abomination, we shall find a god; where we had thought to slay another, we shall slay ourselves; where we had thought to travel outward, we shall come to the center of our own existence. And where we had thought to be alone, we shall be with all the world.”

According to Campbell, in the center of the labyrinth, which is our own psyche, we shall find a god (or the Goddess), and we shall slay our (ego-)selves, and become one with the world. Elsewhere, Campbell writes that this is precisely the function of rituals of death and rebirth:

“When the will of the individual to his own immortality has been extinguished—as it is in rites such as these—through an effective realization of the immortality of being itself and of its play through all things, he is united with that being, in experience, in a stunning crisis of release from the psychology of guilt and mortality.”

This is what I hope to experience, in part through the ritual of sacramental eating. And in fact, it is possible that, of all the rituals I perform as a Neopagan, this one holds the greatest possibility for transformation.