|

|

I blog, therefore I am

|

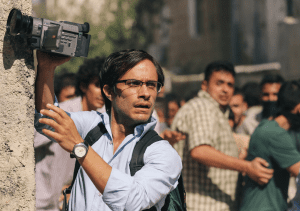

Midway through the movie “Baghdad Blogger,” Salam Pax records a video journal entry from his hotel in Kerbala, Iraq just hours after a lethal suicide bomb attack killing 143 in the holy shrine of Imam Husain.

Pax briefly comments on the attack and then says he longs to return to Baghdad because he has not shaved in a few days and his beard itches.

The episode is a telling example of how Pax views his native Iraq�he appears irritated and inconvenienced by the backdrop of war and aloof to the concerns of his fellow Iraqis.

Salam Pax is the nom de plume of a 30-something Iraqi architect who started a blog in 2003 to keep in touch with his friend Raed. In an article he wrote for the Guardian, Pax explained: “To tell you the truth, sharing with the world wasn’t really that high on my top five reasons to start a blog. It was more about sharing with Raed, my Jordanian friend who went to Amman after we finished architecture school in Baghdad�.so instead of writing emails and then having to dig them up later it would all be there on the blog. So Where is Raed? started.” Pax’ blog soon gained international recognition and he was no longer just a blogger from Iraq but the blogger of Iraq.

What made Pax’s blog powerful was his humor, clarity and remarkable emotional restraint. His film, however, lacks these qualities.

Stylistically, Pax has given little thought to the format of his film. I watched the film at the US premiere on Friday night at the DC Film Festival and I am told that the film may be re-cut before final distribution. The film is divided into seven video entries. Each entry starts with Pax typing on his Hewlett Packard laptop in an empty courtyard of an Iraqi building. Much of the reel time is spent on Pax typing, with long close-ups of his fingers, the keyboard, or oddly, his eyebrows or his ears. Each segment ends with Pax closing the lid of his laptop, looking glib. The long shots of his laptop make the viewer wonder if Pax received royalties from HP. In between shots of him typing, Pax communicates to the viewer using placards with phrases written like “It was really worth it.” But what good is the use of the visual medium if Pax expects his viewers to watch him type or read his hand written signs?

The stylistic shortcomings of the film, however, pale in comparison to the substantive problems. Watching his film is like watching an infomercial by the US government selling the benefits of the war to a disbelieving audience. Pax’s Iraq is a reflection of how the US administration wants Iraqis to measure their freedom.

The film starts with Pax trying to purchase liquor and we hear Pax forecasting Iraq’s future by whether or not the new political (and religious) parties will allow liqueur consumption. In another scene, Pax seems excited that the Iraqi Orchestra can again practice (albeit in the protected “Green Zone”) or that ballet lessons are now taught.

But is tolerance and secularism measured by its willingness to allow a people to drink or dance? In a country where, according to Iraqi body count, 17,384 have been killed, should we find reason to rejoice in such seemingly trivial advances?

Pax repeatedly tells us that the war was worth it because it has brought change and change, he reminds us, is always good. But is it?

In one of his video entries, Pax travels south to visit the holy Shia cities of Najaf and Kerbala to witness Ashura. Shias in Iraq are better off, he tells us, because they can now openly practice their religious traditions like the Ashura procession. But while Pax pleads for Iraqis to respect each group’s cultural and religious traditions, Pax mocks the very traditions that he does not understand or support. When he rhetorically asks what there is to do while visiting Kerbala, he says: “Walk around a cage (ie tomb of a saint), make a wish, kiss the cage, and then repeat.” At times, Pax’s condescending description (and factually incorrect) understanding of Shiism is ironically similar to the letters of Wahhabi extremist Abu Musab Al Zarqawi.

Pax spends a considerable amount of the movie either in the Shia south or in addressing the rise of Shia political parties in Iraq. When visiting Kerbala, he wonders why so many Iranians are in Kerbala. He does not, however, think to interview any of these Iranian pilgrims, choosing instead to give his own reasons. Perhaps if he did he would discover that nearly two million people visit Imam Husain’s tomb on the holy day of Ashura and that these visits occurred during Saddam Hussein’s rule as well.

Pax sees the influx of Iranian pilgrims, however, as a commentary on Shias. After spending the day in Kerbala, he asks, “I need to know if these Shia are Shia first or Iraqi first?”

Pax does not bother to ask this same question of Sunni Iraqis or of Kurds (who he says live on another planet). In Pax’s film, Shia Iraqis are portrayed by their worst stereotype: the chest beating, irrational Shia with loyalty to Iran, the hotheaded cleric (Moqtadar Sadr) who exploits the “idle time” of his followers, and the chador clad women who wail in public.

When addressing Iraq’s growing sectarian violence, Pax reminds his viewer that under Sadaam Hussein the Ashura procession was never held. He fails to mention, however, that suicide bombing at Shias mosques has also never occurred in Iraq’s history.

These realities are conveniently avoided in Pax’s film. What Pax seems to be asking his fellow Iraqis is why are they not like himself? In one of the last segments, Pax explains that because he will be addressing the issue of women in Iraq, he will not be seen during the segment.

It is an admirable intention but we are still not free from his voiceover. In one interview a Muslim woman in hijab speaks about how Islam can empower women and give them equal rights if practiced properly. But Pax interjects and says that such balance in Islam is not found. Pax is unwilling (or is it unable?) to allow Iraqis to have their own voice or to disagree with his thesis that the war was in fact worth it.

Pax has left blogging (at least for now) and currently writes a column for the Guardian. In his debut article, he wrote, “One of the first people to link to the blog said, ‘It is all about a guy who risked his nuts to tell us he’s a pervert and his friend likes to watch.’ I still don’t really understand how it became what it is now.”

Those who watch his film will wonder the same.

Zahir Janmohamed has been blogging for two weeks and is already addicted. Read his personal blog at www.falloficarus.blogspot.com and his group blog at www.qiyamahforecast.blogspot.com