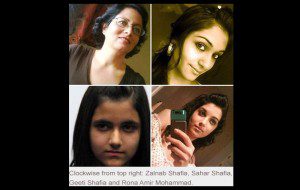

The Canadian trial of three individuals accused of murdering their family members has come to an end. Mohammad Shafia, his wife Tooba Yahya and their son Hamed were found guilty of first-degree murder in the deaths of the Shafias’ three daughters and the Shafia’s first wife. In police wiretaps, Mohammad Shafia is reported to have said that the girls dishonoured and betrayed the family and Islam.

In his ruling, the judge noted that, “it is difficult to conceive of a more despicable, more heinous crime. The apparent reason behind these cold-blooded, shameful murders was that the four completely innocent victims offended your completely twisted concept of honour, a notion of honour that is founded upon the domination and control of women.”

The connection that may exist between honour killings and Islam has been covered extensively. And, in the aftermath of the trial, Canadian Muslims set up the Family Honour Project, to help prevent “honour”-related violence from taking place. Many imams across the country gave coordinated Friday sermons against the practice, and others recently issued a fatwa to the same effect.

But for the vast majority of Canadian Muslim women, the idea of honour killings has little connection to religious and familial values and is therefore is beyond the realm of possibility. What Muslims aren’t talking about are attitudes that — while certainly not at the level of honour killings — seek to establish control and exert power over the thoughts and actions of Muslim youth by their parents or guardians.

Under an Iron Thumb

Denouncing honour killings is the easy part, but other gradations of control can be pretty harmful for youth, especially young women, as well. Before the gruesome murder of the Shafia girls, they were under the iron thumb of their father: They complained to social workers about domestic violence directed at them. One of the girls was forbidden from going to school for a year because she was discovered in a romantic relationship. At one point, the sisters were afraid to return home after school for fear of facing their father’s wrath. Their brother, Hamed, was enlisted to watch the girls, admonish them and report wrongdoings to his father.

These cases are not isolated. I know other young Muslim women whose lives have been overly constrained by their parents – and particularly their fathers. In one case, a friend of mine was made to wear the hijab (headscarf) against her will. Unlike her brother, she was forced to return home by dusk every day. She had her phone monitored by her parents. She was discouraged from pursuing a higher education. And even as a teenager, she was beaten for what seemed to be minor infractions. Eventually she left home and has since had little association with her family.

From interactions with Muslims in my community, it is clear to me that young Muslim women face significantly more pressure than men to be more religious or to behave in a more conservative manner — to not be so outspoken, to pursue specific avenues of schooling, or to fit into certain prescribed roles in the household or the community. Some have argued that this is because the family’s reputation rests primarily on the conduct of its girls and women; others have insisted it is because parents continue to hold the belief that a woman’s chastity is the responsibility of the family, and they are particularly fearful of the outcome of any sexual impropriety. But even if females face the brunt of it, young Muslim males can also have difficulty coping with strict parental control and familial pressure.

Freedom v. Religious Traditions

Many people immigrated to Canada seeking a better life for themselves and for their children. They revel at the freedom to shape their own destinies. But they often fail to understand that freedom has its costs too. For the most part, we are free to do whatever we want so long as we do not harm others. We live in a country in which freedom is not just constitutionally protected but also celebrated and cultivated.

It begins in public educational institutions – young people are not expected to automatically obey authority figures or cultural norms; they are encouraged to develop an intellectual curiosity; to ask questions and challenge traditional boundaries. So for many young people today, the prospect of blindly following cultural or religious traditions no longer has much worth.

What are parents to do? How can they raise their children to be “good Muslims” without making them feel like religion is being forced upon them? To begin, parents need to realize that they are raising children in a context that is different from their homeland. For this reason, many of the old wisdoms about how best to raise children need to be reworked. Parents need to realize they cannot control their children. They can educate them, they can inculcate moral and religious values and principles, but they cannot exert force. That’s not the way to raise children with faith in this part of the world.

Parents cannot command their children to fulfil any of the requirements of faith. Even on a practical level, parents who force their children to pray will find that they cannot monitor their children at all times to ensure that the five daily prayers are performed. For parents who force their children to wear particular kinds of clothing – yes, some will obey, but teachers will attest to the creativity of Muslim students in altering their appearance once out of their parents’ sight.

The Shafia girls were known to have done this. And despite the control that Mohammed Shafia had, the girls still found ways to rebel. Cell phone photos revealed the eldest in her underwear; another was in the embrace of her clandestine boyfriend. There were condoms found in one daughter’s bedroom, suggesting that she had experimented with pre-marital sex. Another was sent home from school for dressing too provocatively.

These details would make many Muslim parents cringe. But domestic violence is not the answer, and neither is fear of punishment or ostracism. Much of one’s faith is internal; being controlled by others leads to belief that is devoid of meaning and action that is adhered to with resentment or hatred. In a society in which religion is denigrated and freedom is deemed paramount, it is easy to abandon faith that is not sustained with deep personal conviction.

Guidance, Not Compulsion, in Religion

Guidance, Not Compulsion, in Religion

If parents have brought their children to this place of freedom, it is imperative that they help them thrive. It is no longer enough to appeal to tradition or authority. This doesn’t mean that parents cannot encourage or admonish their children to behave or act in ways that are in keeping with their religious understanding. What it does mean, however, is that parents need to cultivate a greater motivation for action amongst their children.

From a young age, parents need to help their children develop a love of God, such that their life is oriented towards wanting to please God. They have to appeal to their children’s minds in order to help them appreciate the wisdom behind God’s commands. When young people become aware of why they have chosen to believe and act in a specific manner, they develop a sense of responsibility for their actions and an understanding of the consequences of violating personal principles such that they desire to walk the path imbued with Islamic principles.

This process cannot be a one-way communication; children need to be allowed to apply their critical thinking skills; to ask questions and offer opinions without facing rebuke. Why can’t they go to the school prom, for example? Why must they believe in God? Why should they pray? Why can’t they have a boyfriend or girlfriend like everyone else? Parents need to be able to engage in conversation and offer answers that make sense to their children. Admittedly, this process of helping children to choose and adhere to faith is a difficult one.

What will help parents is if they are able to empathize with the struggles their children experience. In their home countries, the societal culture would have served as a support because the community shared many social mores. Here, religious and ethnic minorities consistently stand out, and religion can seem to pose continuous restrictions that are difficult to abide by. Young Muslim women, for example, may find it difficult to dress modestly in a society in which it is seen as acceptable for women to wear skimpy skin-tight clothing. For teenagers, it can be difficult to look and sound different.

If parents come to appreciate the real difficulties young people face trying to live by traditional values within a societal culture that revels in and rewards freedom, they will feel less frustrated or angry when their children occasionally fall short of their expectations.

Finally, parents need to respect that their youth have the capacity and freedom to think, to make decisions for themselves, and chart their own paths. Many verses in the Qu’ran call on believers to question, be critical, and reason. Sometimes young people will do things that are contrary to their parents’ wishes. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they are wrong. Sometimes they will do things that are contrary to God’s commands. That doesn’t mean they are a lost cause. They could very well turn back to God after a brief fling of teenage rebellion, and God could very well forgive them.

Ultimately, parents are their children’s first and best role models, and they are responsible for teaching, supporting and encouraging their children from a young age. If parents have not done so, then they are responsible to God for not fulfilling the role entrusted to them. If they have done what they can, then the rest must be left to God. Like the prophets of the past whose relatives turned away from God, parents are not accountable for what their offspring believe or do once they have reached adulthood; they can only pray and hope for the best. There is no compulsion in faith, God says. Perhaps we should work on inculcating that principle in our homes.

Safiyyah Ally is a Ph.D candidate in Political Science at the University of Toronto. She is interested in the role of conscience in religion.