By Margari Hill

On November 21st, the Muslim Anti-Racism Collaborative kick-started the #BlackInMSA hashtag. It began with a conversation on our steering committee’s WhatsApp group about the current tensions between black students and their non-black peers in Muslim Student Associations the night before. This conversation was important given the current struggle Black Muslim students face in light of Islamophobia and #BlackLivesMatter.

I tweeted about my own 15 years of experience with Muslim student organizing. Over the years, I have found that children of African immigrants and descendants of enslaved Africans, Black Muslims in the United States, are often silenced and sidelined in discourses on what it means to be black in this country, as well as what it means to be Muslim. I experience marginalization my intersecting identities as a Black American Muslim woman. But Black Muslim women remain some of the most powerful voices to challenge dominant narratives.

While the twitter conversation focused on black experiences in Muslim settings, the conversation could have easily been #MuslimInBSU (Black Student Union). There was little said about the diversity of beliefs within the African Diaspora. At my Pan African student graduation ceremony at Stanford years ago, a speaker mentioned the church and temple as a cornerstone for our community but left out the mosque.

I have experienced anti-Muslim bigotry from my own community. I’ve been insulted on the street and in college cafeterias. One evangelical brother swore up and down that Muslims don’t use soap and deodorant, when in fact Europeans learned of soap during the Crusades in Aleppo. Su’ad Abdul Khabeer, Assistant professor of Anthropology at Purdue, has written about Black Islamophobes.

Recently when I visited Vanderbilt University, I thought about how Carol Swain’s anti-Muslim op-ed, and wondered how it would fare in her course.

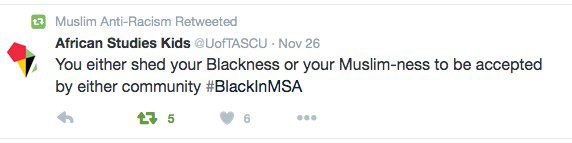

@UofTASCU wrote. “You either shed your Blackness or your Muslim-ness to be accepted by either community #BlackInMSA.”

@UofTASCU wrote. “You either shed your Blackness or your Muslim-ness to be accepted by either community #BlackInMSA.”

Black Muslim women are often judged for the personal choices we make. When our practice is non-normative, we are judged by our non-Muslim, often Christian, families for not being “real Muslims.” When we become more devout, our friends and relatives sometimes put us down for being phony now that we’ve changed.

Our spiritual journey becomes a subject of jokes, derision, and name-calling. I have heard people describe the Muslim garb as bat suits or wearing garbage bags. I have seen Black women on twitter speculating what is under our scarves, daring each other to snatch off one of our scarves.

But the anti-Muslim sentiment is not just about hurt feelings. There are real world consequences for women like me. In “A Serious Function of Racism,” Makka Ali writes “I’m just as Black as I am Muslim as I am female and my understanding of oppression is heavily influenced by my experience as a member of any one of these groups.”

Carolyn Moxley Rouse’s Engaged Surrender and Jamillah Karim’s American Muslim Women are two important works to understand the ways in which Muslim women navigate multiple oppressions. As Black Muslim women, we have to fight on numerous fronts facing deadly force, sanctioned violence, detainment and surveillance.

Our gender, our race and our faith make us more vulnerable. We are profiled racially and religiously, often with little support from the multiple communities in which we belong. Through it all, our faith sustains us.

Black American Muslim women are also marginalized by the cultural hegemonies that plague the American Muslim community. With one-third Black American, one-third South Asian and one-third Arab, American Muslims are one of the most diverse religious groups. Makka Ali explains, “ … from conversations with my Muslim peers whose families are from other countries, I learned that they didn’t have as much of an understanding of or concern about racism before the widespread backlash against Muslims began.”

Since 9/11, non-Black Muslims have decried the anti-Muslim bigotry and xenophobia they have faced. The pressure is intense, coming from the Islamophobia industry, laws and programs that target Muslims and media coverage that often leads to spikes in anti-Muslim bias. Anti-Islamophobia activism in the American Muslim community has been led by immigrants, as well as second and third generation American Muslims who have often measured their sense of belonging relative to their acceptance by white Americans.

Most non-Black Muslim national organizations have not rooted their civil rights advocacy in black liberation struggles. And only a few have begun to build multi-racial coalitions to address racial profiling. Some argue that our blackness makes us immune to Islamophobia. But look at Robert Doggart, a white Christian minister who plotted to attack the predominantly Black Muslim Islamberg, And, recently the FBI went on alert because armed anti-Muslim protester Jon Ritzheimer threatened the same community. However, because the targets are Black and Muslim, the terrorist threat draws little media attention.

In terms of media representation of American Muslims, Black Muslim women are often erased. A recent example was a featured segment on Muslims on the Today Show, which failed to include a Black Muslim among the five guests. In many ways, this fits the stereotype that Muslims only come from the Middle East and South Asia.

But slowly, the image is shifting in both media portrayals and in community life. This year Regina King won an Emmy for portraying a Black Muslim woman.

We have powerful Muslim women who have been game changers. This year, the Islamic Society of North America brought community organizer, motivation speaker and author Ilyasah Shabazz, the daughter of Malcolm X, on as a main speaker. We have Mara Brock Akil and Ameena Matthews who have shown also shown us how Black Girls Rock. Black Muslim women, who come from all parts of the African Diaspora, have been a powerful force in dispelling stereotypes and building community.

Margari Aziza Hill is co-founder and Programming Director of Muslim Anti-Racism Collaborative (MuslimARC), assistant editor at AltM, columnist at MuslimMatters, and co-founder of Muslims Make it Plain. An educator and independent researcher, she has given talks and lectures at various universities and Muslim community organizations across the country. Find her on Twitter @margari_aziza and on her blog here.