By Zeba Khan

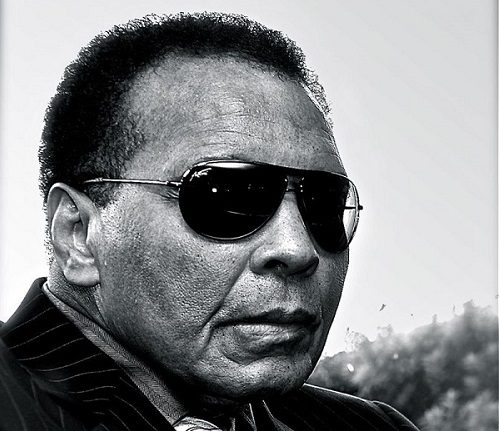

Bernie Sanders rightly spoke out on the hypocrisy of people like Donald Trump, who praise Muhammad Ali in one breath and disparage his religious brethren in another: “Don’t tell me how much you love Muhammad Ali and yet you’re going to be prejudiced against Muslims in this country,” the senator said.

For many American Muslims, we know all too well that growing up Muslim in America often feels like playing one long game of defense against attacks on our faith and our identity. Because of that, Sanders’ words are a welcomed and much appreciated acknowledgement of the barrage of animosity, bigotry and vitriol we face. Indeed, there is something powerful in having others bear witness, if nothing else, to one’s trials.

But as we prepare to lead the nation and the world in saying goodbye to the beloved global icon, during the month of Ramadan no less, we would also do well to take the opportunity to reflect inwards and ask ourselves if a form of the hypocrisy Sanders called out in mainstream culture also exists within our own communities – specifically against Muslims who may look more like the boxing legend or the also recently passed Helena Chavez, than a Bollywood heartthrob.

A recent study released by the nonprofit Muslim Anti-Racism Collaborative found that 59 percent of all American Muslims surveyed reported experiencing discrimination from other Muslims. While Muslims from every ethnic background experienced some level of rejection from within their faith community, overwhelmingly Black, Hispanic, mixed race and white convert Muslims experienced the brunt of it.

Consider the statistics: 89 percent of Hispanic and American Indian Muslims, 79 percent of Black and mixed race Muslims and 64 percent of white convert Muslims said they’d been discriminated against by other members of their faith community. By contrast, only 35 percent of Arab and 48 percent of South Asian Muslims reported experiencing any discrimination.

Human beings are social creatures by nature who want to feel accepted by others. When we aren’t, it hurts. It’s easy to see how that is when thinking on a personal level. If you were bullied as a kid or ever rejected by a romantic partner, for example, those moments never feel good and can have long-lasting effects.

The same holds true at the group level. Being rejected by other groups, particularly if you’re part of a minority group, hurts. Numerous studies have shown how that rejection negatively impacts the mental and physical health of those ostracized minorities. Given this, and a 2015 poll that found 55 percent of Americans held an unfavorable opinion of our faith, it’s not surprising then there was a spike in Muslim teens reaching out for mental and emotional help through a text messaging hotline at the end of last year.

As heartbreaking as that is, the sad truth is that a similar dynamic is happening within our communities that is likely having a compounding negative impact on some of our most vulnerable populations.

Some researchers have begun to hypothesize that being rejected by your community has an even worse affect that being rejected by someone outside your community. It makes sense. After all, rejection from within is to call into question your identity as part of that community. Black Muslims in the U.S., for example, know this dynamic all too well, where their religious journeys are sometimes viewed as somehow less authentically Islamic by other Muslims.

One Black Muslim friend preemptively addressed non-Black Muslims in a Facebook note once news of Muhammad Ali’s deteriorating health was public: “Do not […] judge his journey to Islam in your commentary. His journey, like that of countless others, represents the history of Islam in America and paved the way for all of us.”

Hispanic and white convert Muslims, too, face social stigma. Often the only members of their families that are Muslim, it’s not uncommon for these minority Muslims to join Muslim communities already feeling isolated. As Melvin Reveillon, an organizer of Hispanic Muslim Day in New Jersey explained, “Not only do we face the stigma of being associated with extremism, but we are also seen as defectors, people who abandoned Christianity and family tradition.”

It is these communities within our communities that need to feel accepted and embraced perhaps more than any others. And yet, we know they are not.

No Muslim should feel discriminated against by other Muslims. Particularly this month, we should do all that what we can to expel this toxicity from our communities. Yet, if we are to truly rid ourselves of this social illness, we have to first acknowledge its existence and its disproportionate existence in the lives of many of our Black, Hispanic, white and mixed race sisters and brothers in faith. It may feel easier to ignore it or pretend it doesn’t exist, but that won’t make it go away.

Undoubtedly the Janaza prayer for our beloved elder, like the interfaith service that follows it, will be a multiracial affair, a reflection of the impact Ali had on all people, no matter their race, color, creed, or class. But as American Muslims, let’s not permit the unity of the moment to be just a flash in the pan in the record of our collective history.

We can make this our watershed moment when each of us — at the individual, family, and mosque level — does the real work of knowing the many tribes our Creator made us into.

Zeba Khan is a writer focused on the intersection of race, religion, and politics in America. Follow her on Twitter @zebakhan