Editor’s Note: The author performed his Hajj pilgrimage in 2008. On the decade anniversary of his holy pilgrimage, here is a piece he wrote in the immediacy of his return, ten years ago.

Having recently returned from Hajj, I am bombarded by that well meaning question by all of my friends and loved ones: “How was it?” Unfortunately, all I can answer is an inadequate “fine,” or even “great.” Why? Words can’t really describe the experience, especially hastily chosen words in a usually hurried conversation.

How was Hajj? Was it awesome? Was it a life changing experience? Was it spiritually fulfilling? Was it physically rigorous? Yes. All that for sure. But, even that seems to leave something out. Not in the level of superlative, but in the level of quality.

To me, Hajj was best described as a journey through death and back. How would you describe that? You simply can’t.

The first thing you learn, even before you leave, is that your Hajj is your own, and no one else’s. Your experiences, your hardships, your prayers, your choices are all unique to you alone. So, it makes sense that this interpretation of Hajj is mine alone and may not be the experience of others. It may not even be “correct” in the sense that I have not gleaned it (to the best of my knowledge) from any sabaq or sanctioned text. Yet to me, it is as plain as day.

Hajj, in many ways like death, is a pinnacle, a climax of a Muslim’s life. Something to be looked at with equal parts excitement, respect and trepidation mixed with a healthy dose of downright fear. And yet you realize that though you may fear it, your life is marching inevitably towards it as a fard (required) act. For me, I felt a call, so clear it was almost physical, that this was my year to go. And when that hit, there really was no choice but for me to make the trek.

The first true act of Hajj is putting on ihram clothes. For men, two simple pieces of unsewn, unadorned white cloth wrapped around your body in much the same way as a traditional burial shroud. You shed every accoutrement and accessory of this world. Everyone looks the same. The cardiologist from Los Angeles was sitting next to the street sweeper from Bangladesh (really!), and nobody could tell one from the other. This was a powerful moment, saying goodbye to the worldly station you have worked so hard to achieve.

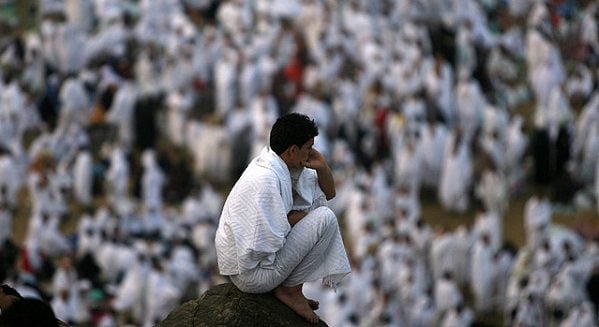

The stay in Arafat is the climax of the act of Hajj. You stand before the sun and pray. Much like the Muslim belief of qiyamat (the day of judgement), you stand before Allah, and you pray. You pray with an intensity you have never before experienced. The most fitting description I have read (but cannot take credit for) is that you stand before your God naked; stripped naked of every crutch or protection you have come to rely on. There are no worldly accessories. It doesn’t matter how much you make or what you own. It doesn’t matter who your dad is or your mom. You may stand next to your spouse, but you are utterly and completely alone.

Standing there in your burial shroud, praying before God, with only your iman (faith) and your eamal (works) to speak on your behalf, stripped of every conceivable comfort or connection of the world. This is an accurate description of Arafat day, but it is also an accurate description of what Muslims are taught will happen to each of us when we are called to account after death.

Arafat is the most exhausting day the of Hajj. Though it is not the most rigorous day, the trip down from the mountain of Arafat is a mixture of feeble jubilation with intense spiritual, psychological and emotional fatigue. Your trip through death is over. Your accounts have been settled. You have been cleansed of sin. But, you have been left with nothing in this world; you sleep under the stars (in Muzdalifah), exposed to the elements. It is time for rebirth.

On your return, you shave your head (men do), just as we do for newly born babies. You begin your new life with a tawaaf (a trip to the Kaaba), hopefully beginning things on the right foot. What better way to start off your new life than with an act of total obedience and submission to God’s will? You return home and remove your (by now dusty and dirty) ihram clothes to begin your life anew.

When I finished, my number one feeling was one of traversing the plains of death, facing its trials and tribulations, and returning reborn.

How do you sum that up in a hallway when a colleague asks “How was your trip?” There’s only one realistic answer. “Fine, thanks.”