I’m slowly but surely working my way through Destroying Mara Forever: Buddhist Ethics Essays in honor of Damien Keown, and came across this thoughtful gem by Peter Harvey:

… Human freedom of will is of a variable nature, increasing with mindfulness and wholesome actions.” p.50

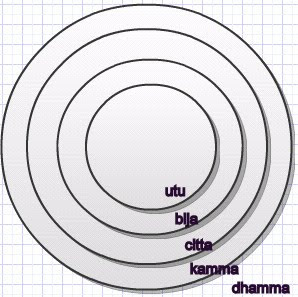

I’ve written before about my theory of “nested causality” in Buddhist thought, represented by the image above. It’s not a prominent or well-formulated system in early Buddhism, and citta (mind) and kamma (action/moral) even swap places in some accounts. But it can be used to show a sort of Buddhist path, or evolution of consciousness.

In the Aggañña Sutta (DN 27) [my quotes are from the Walshe translation] a reverse evolution is described, beginning with a contraction of the world (think “big-crunch”) and beings mostly being born in a high godly realm, the “realm of devas of streaming radiance.” But then the world begins to expand again (big bang?) and those beings begin to be reborn in this world. Now these beings are not ordinary every-day beings, mind you. But instead they are said to “dwell, mind made, feeding on delight, self-luminous, moving through the air, glorious.”

“At that time there was just one mass of water and all was darkness, blinding darkness.” Interesting. There was no sun or moon, and only after a while did earth appear. But it was not ordinary earth; it was “the color of pure ghee… and sweet, like pure wild honey.” So we have self-luminous beings floating in the air over this tasty land. Just guess what happens next. One of these beings, stricken with greed, decides to taste the earth, “and craving arose in it [this being].”

So we have a moral tale about the origin of craving – the second Noble Truth. Over time the beings grew greedier, ate more, got ugly, grew legs; grew different in appearance, “the good-looking ones despising the others,” and so on for a long time. The food disappeared, new stuff arose, the beings changed more, grew sex-organs and now lust developed and soon sexual activity ensued. This made the lust-free beings very angry and they cast out those who had had sex, who then built houses “so as to indulge under cover.” From here all goes to hell (metaphorically – literally a bit later), as people steal land, practice poor agriculture and ultimately elect a leader in hopes that this will calm things down.

And so, with a king, people see that things are a mess and decide to “put aside evil and unwholesome things” which, says the Buddha, is the origin of the name, “Brahmin.” The other castes likewise get their names from their original activities. And just so, it is one’s moral activities that determine one’s future life and/or awakening. The one who has done the moral work of eliminating the greed, hatred, and delusion borne of our current state is to be considered “chief among men in relation to the Dhamma.“

… Human freedom of will is of a variable nature, increasing with mindfulness and wholesome actions.” p.50

With increasing mindfulness, we move out of the house, so to speak, through the fields, toward a cessation of kamma, the re-purification of mind/citta, and release to the Dhamma. It is like weaving a spiral path through the diagram.

As I mentioned recently, narratives like this tend to be problematic. First of all, they are easily misunderstood – especially as they are divorced form their original context. Richard Gombrich, an eminent British Buddhologist, argues that this “myth” is foremost a comical critique of the Brahmanic origin myth, not to be taken seriously. This may be correct. But I am convinced by such scholars as Rupert Gethin, another great British scholar, that we are wise to take a second look and see what meditative value such an odd story might have.

In this light it seems clear that the hearer, if not laughing over witty references to Brahmanic stories, would reflect upon the nature of his/her own motivations and the results thereof. Anyone who has meditated much knows the sense of freedom, lightness (self-luminosity? floating through air?), etc that comes with a good meditation or retreat. And likewise we know how our mind can get preoccupied with fine food, possessions, the opposite sex, and so on. And we know that all of these are disastrous! Well, maybe not so fast. But for the monks listening to the Buddha they would have been.

So the tale is a moral one, to be meditated on, for the sake of an evolution of consciousness, a development of free will.