Margaret’s comment on my last post got me thinking (which I always appreciate – thanks Margaret :). So I propose a bit of a study session on one of the suttas most commonly cited in the ethics of meat-eating. Included is the full Pāli of the text as well as a reputable English translation. Please read, comment, ask questions, answer them, etc. I’ll try to keep up 🙂

Meat eating vs Vegetarianism is a common topic amongst Buddhists and has passed in and out of various fads in the West in the last few decades. The arguments and discussions have many angles: ethics toward sentient beings, what’s best for our planet, and personal health being chief amongst them.

Do you want my thoughts first or the Buddha’s? Well, we’ll start with mine because they’re shorter, then get to the Buddha’s.

- We should avoid harm to sentient beings, right down to flies, flees, ticks, etc. You don’t need to believe in reincarnation to see the wisdom of this. Read Sir (Saint) Thomas More’s Utopia

. How we treat other beings, right down to the bacteria on our body, reflects in how we treat fellow humans. Children who abuse cats when young become sociopaths later in life (or so Law and Order tells me).

- When we do need to harm other beings, do so with respect and humility. A Native American traditionally killing an elk or buffalo has far more respect from me than a punk who thinks it’s funny to run over a squirrel with his car. In Buddhism it is our intention (cetanā) that generates our action (karma). It is an unfortunate consequence of Western culture and ethics that actions are superficially lumped together and evaluated.

- Our planet. Yikes. Well I’m pretty convinced that humans are causing climate change and that we need to do something about it. There are about a million and one things you can do to help, and as many to cause more harm. It’s my impression that a vegan lifestyle, or as close as one can get to it, helps. Eating local or raising your own (even meat) is also helpful, as it reduces carbon from shipping food all over the planet. Depending on your location, either of these may be difficult. But it’s not about absolutes, it’s about effort and intention.

- Personal health? Be wise, educate yourself, talk to friends, be very mindful of changes you make and how they affect your body/energy levels. When I first went vegetarian, from a solid diet of steak and potatoes, I lived on Chex-mix and dairy products for a while, much to my own demise. It took time and help from friends to shift to healthy foods and a healthy lifestyle.

Sheesh. Hopefully not too long winded there, ’cause the Buddha’s worse… Here it is in the Pāli via here.**

5. Jīvakasuttaṃ

51. Evaṃ me sutaṃ – ekaṃ samayaṃ bhagavā rājagahe viharati jīvakassa komārabhaccassa ambavane. Atha kho jīvako komārabhacco yena bhagavā tenupasaṅkami; upasaṅkamitvā bhagavantaṃ abhivādetvā ekamantaṃ nisīdi . Ekamantaṃ nisinno kho jīvako komārabhacco bhagavantaṃ etadavoca – ‘‘sutaṃ metaṃ, bhante – ‘samaṇaṃ gotamaṃ uddissa pāṇaṃ ārabhanti [ārambhanti (ka.)], taṃ samaṇo gotamo jānaṃ uddissakataṃ [uddissakaṭaṃ (sī. pī.)] maṃsaṃ paribhuñjati paṭiccakamma’nti. Ye te, bhante, evamāhaṃsu – ‘samaṇaṃ gotamaṃ uddissa pāṇaṃ ārabhanti, taṃ samaṇo gotamo jānaṃ uddissakataṃ maṃsaṃ paribhuñjati paṭiccakamma’nti, kacci te, bhante, bhagavato vuttavādino, na ca bhagavantaṃ abhūtena abbhācikkhanti, dhammassa cānudhammaṃ byākaronti, na ca koci sahadhammiko vādānuvādo gārayhaṃ ṭhānaṃ āgacchatī’’ti?

52. ‘‘Ye te, jīvaka, evamāhaṃsu – ‘samaṇaṃ gotamaṃ uddissa pāṇaṃ ārabhanti, taṃ samaṇo gotamo jānaṃ uddissakataṃ maṃsaṃ paribhuñjati paṭiccakamma’nti na me te vuttavādino, abbhācikkhanti ca maṃ te asatā abhūtena. Tīhi kho ahaṃ, jīvaka, ṭhānehi maṃsaṃ aparibhoganti vadāmi. Diṭṭhaṃ, sutaṃ, parisaṅkitaṃ – imehi kho ahaṃ, jīvaka , tīhi ṭhānehi maṃsaṃ aparibhoganti vadāmi. Tīhi kho ahaṃ, jīvaka, ṭhānehi maṃsaṃ paribhoganti vadāmi. Adiṭṭhaṃ, asutaṃ, aparisaṅkitaṃ – imehi kho ahaṃ, jīvaka, tīhi ṭhānehi maṃsaṃ paribhoganti vadāmi.

53. ‘‘Idha, jīvaka, bhikkhu aññataraṃ gāmaṃ vā nigamaṃ vā upanissāya viharati. So mettāsahagatena cetasā ekaṃ disaṃ pharitvā viharati, tathā dutiyaṃ, tathā tatiyaṃ, tathā catutthaṃ. Iti uddhamadho tiriyaṃ sabbadhi sabbattatāya sabbāvantaṃ lokaṃ mettāsahagatena cetasā vipulena mahaggatena appamāṇena averena abyābajjhena pharitvā viharati. Tamenaṃ gahapati vā gahapatiputto vā upasaṅkamitvā svātanāya bhattena nimanteti. Ākaṅkhamānova [ākaṅkhamāno (syā. kaṃ.)], jīvaka, bhikkhu adhivāseti . So tassā rattiyā accayena pubbaṇhasamayaṃ nivāsetvā pattacīvaramādāya yena tassa gahapatissa vā gahapatiputtassa vā nivesanaṃ tenupasaṅkamati; upasaṅkamitvā paññatte āsane nisīdati. Tamenaṃ so gahapati vā gahapatiputto vā paṇītena piṇḍapātena parivisati. Tassa na evaṃ hoti – ‘sādhu vata māyaṃ [maṃ + ayaṃ = māyaṃ] gahapati vā gahapatiputto vā paṇītena piṇḍapātena pariviseyyāti! Aho vata māyaṃ gahapati vā gahapatiputto vā āyatimpi evarūpena paṇītena piṇḍapātena pariviseyyā’ti – evampissa na hoti. So taṃ piṇḍapātaṃ agathito [agadhito (syā. kaṃ. ka.)] amucchito anajjhopanno[anajjhāpanno (syā. kaṃ. ka.)] ādīnavadassāvī nissaraṇapañño paribhuñjati. Taṃ kiṃ maññasi, jīvaka , api nu so bhikkhu tasmiṃ samaye attabyābādhāya vā ceteti, parabyābādhāya vā ceteti, ubhayabyābādhāya vā cetetī’’ti?

‘‘No hetaṃ, bhante’’.

‘‘Nanu so, jīvaka, bhikkhu tasmiṃ samaye anavajjaṃyeva āhāraṃ āhāretī’’ti?

‘‘Evaṃ, bhante. Sutaṃ metaṃ, bhante – ‘brahmā mettāvihārī’ti. Taṃ me idaṃ, bhante, bhagavā sakkhidiṭṭho; bhagavā hi, bhante, mettāvihārī’’ti. ‘‘Yena kho, jīvaka, rāgena yena dosenayena mohena byāpādavā assa so rāgo so doso so moho tathāgatassa pahīno ucchinnamūlo tālāvatthukato anabhāvaṃkato [anabhāvakato (sī. pī.), anabhāvaṃgato (syā. kaṃ.)] āyatiṃ anuppādadhammo. Sace kho te, jīvaka, idaṃ sandhāya bhāsitaṃ anujānāmi te eta’’nti. ‘‘Etadeva kho pana me, bhante, sandhāya bhāsitaṃ’’ [bhāsitanti (syā.)].

54. ‘‘Idha, jīvaka, bhikkhu aññataraṃ gāmaṃ vā nigamaṃ vā upanissāya viharati. So karuṇāsahagatena cetasā…pe… muditāsahagatena cetasā…pe… upekkhāsahagatena cetasā ekaṃ disaṃ pharitvā viharati, tathā dutiyaṃ, tathā tatiyaṃ, tathā catutthaṃ. Iti uddhamadho tiriyaṃ sabbadhi sabbattatāya sabbāvantaṃ lokaṃ upekkhāsahagatena cetasā vipulena mahaggatena appamāṇena averena abyābajjhena pharitvā viharati. Tamenaṃ gahapati vā gahapatiputto vā upasaṅkamitvā svātanāya bhattena nimanteti. Ākaṅkhamānova, jīvaka, bhikkhu adhivāseti. Sotassā rattiyā accayena pubbaṇhasamayaṃ nivāsetvā pattacīvaramādāya yena gahapatissa vā gahapatiputtassa vā nivesanaṃ tenupasaṅkamati; upasaṅkamitvā paññatte āsane nisīdati. Tamenaṃ so gahapati vā gahapatiputto vā paṇītena piṇḍapātena parivisati. Tassa na evaṃ hoti – ‘sādhu vata māyaṃ gahapati vā gahapatiputto vā paṇītena piṇḍapātena pariviseyyāti! Aho vata māyaṃ gahapati vā gahapatiputto vā āyatimpi evarūpena paṇītena piṇḍapātena pariviseyyā’ti – evampissa na hoti. So taṃ piṇḍapātaṃ agathito amucchito anajjhopanno ādīnavadassāvī nissaraṇapañño paribhuñjati. Taṃ kiṃ maññasi, jīvaka, api nu so bhikkhu tasmiṃ samaye attabyābādhāya vā ceteti, parabyābādhāya vā ceteti, ubhayabyābādhāya vā cetetī’’ti?

‘‘No hetaṃ, bhante’’.

‘‘Nanu so, jīvaka, bhikkhu tasmiṃ samaye anavajjaṃyeva āhāraṃ āhāretī’’ti?

‘‘Evaṃ, bhante. Sutaṃ metaṃ, bhante – ‘brahmā upekkhāvihārī’ti. Taṃ me idaṃ, bhante, bhagavā sakkhidiṭṭho; bhagavā hi, bhante, upekkhāvihārī’’ti. ‘‘Yena kho, jīvaka, rāgena yena dosena yena mohena vihesavā assa arativā assa paṭighavā assa so rāgo so doso so moho tathāgatassa pahīno ucchinnamūlo tālāvatthukato anabhāvaṃkato āyatiṃ anuppādadhammo. Sace kho te, jīvaka, idaṃ sandhāya bhāsitaṃ, anujānāmi te eta’’nti. ‘‘Etadeva kho pana me, bhante, sandhāya bhāsitaṃ’’.

55. ‘‘Yo kho, jīvaka, tathāgataṃ vā tathāgatasāvakaṃ vā uddissa pāṇaṃ ārabhati so pañcahi ṭhānehi bahuṃ apuññaṃ pasavati. Yampi so, gahapati, evamāha – ‘gacchatha, amukaṃ nāma pāṇaṃ ānethā’ti, iminā paṭhamena ṭhānena bahuṃ apuññaṃ pasavati. Yampi so pāṇo galappaveṭhakena [galappavedhakena (bahūsu)] ānīyamāno dukkhaṃ domanassaṃ paṭisaṃvedeti, iminā dutiyena ṭhānena bahuṃ apuññaṃ pasavati. Yampi so evamāha – ‘gacchatha imaṃ pāṇaṃ ārabhathā’ti, iminā tatiyena ṭhānena bahuṃ apuññaṃ pasavati. Yampi so pāṇo ārabhiyamāno dukkhaṃ domanassaṃ paṭisaṃvedeti , iminā catutthena ṭhānena bahuṃ apuññaṃ pasavati. Yampi so tathāgataṃ vā tathāgatasāvakaṃ vā akappiyena āsādeti, iminā pañcamena ṭhānena bahuṃ apuññaṃ pasavati. Yo kho, jīvaka, tathāgataṃ vā tathāgatasāvakaṃ vā uddissa pāṇaṃ ārabhati so imehi pañcahi ṭhānehi bahuṃ apuññaṃ pasavatī’’ti.

Evaṃ vutte, jīvako komārabhacco bhagavantaṃ etadavoca – ‘‘acchariyaṃ, bhante, abbhutaṃ, bhante! Kappiyaṃ vata, bhante, bhikkhū āhāraṃ āhārenti ; anavajjaṃ vata, bhante, bhikkhū āhāraṃ āhārenti. Abhikkantaṃ, bhante, abhikkantaṃ, bhante…pe… upāsakaṃ maṃ bhagavā dhāretu ajjatagge pāṇupetaṃ saraṇaṃ gata’’nti.

Jīvakasuttaṃ niṭṭhitaṃ pañcamaṃ.

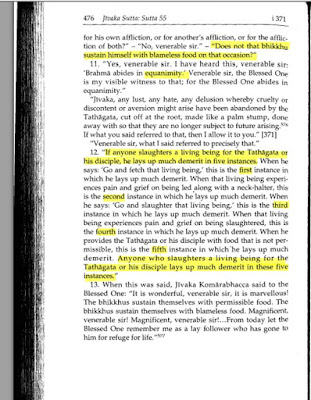

And since I’m too lazy and incompetant to even try a translation of that, we’ll stand on the shoulders of giants: with Bhikkhu Nanamoli and Bhikkhu Bodhi’s translation of the Majjhima Nikaya here (click for larger images):

The sutta seems to set up two standards (neither of which exhausts our discussion of vegetarianism in Buddhism, but both help). The first is for a monk. For the monastic, meat should not be eaten if it is seen, heard, or suspected [to have been prepared for him]. But meat may be eaten otherwise.

I often say this is my own “I didn’t know and I’m not gonna fuss” rule. In London, a Korean friend’s mother invited me to a huge meal upon hearing that I was a Buddhist. It was 80% meat products. I ate it. It would have been rude to say, “hey, I’m a vegetarian, sorry I can’t accept your generosity.” That would have made everyone uncomfortable, and me hungry – nibbling on the few veggies. It would have made no difference to the animals already bred, raised, fed, and killed for the meal.

The second standard is for the layman. Here again intentions are key. It says that “anyone who slaughters a living being for the Buddha or his student, he lays up much demerit in five ways.” First by saying “go get the animal to be killed”; second when the animal experiences pain; third when he says “go kill the animal”; fourth when the animal is in the pain of being slaughtered; and fifth when he offers the food to the Buddha or his student.

ANALYSIS:

For one thing, we shouldn’t take this, or any of the Buddha’s teachings, at face value. We are constantly urged to test them in our lives, to discuss them with wise people, and to see what brings about the reduction in our own greed, hatred, and delusion. As Margaret noted, vegetarianism can become an attachment, and this is far, far from what the Buddha would have suggested (*see below/bottom for a hint of this). The Buddha may have prescribed many exterior activities to monks and laypeople, but that does not mean that those activities are necessarily right for us. Central to Buddhist thought is that we each must learn and decide for ourselves – not without help, but ultimately it is up to us to realize the truth, not to accept or believe it as in some systems of thought.

What’s (to me) very interesting about this sutta is that it intermingles discussion of loving-kindness (mettā) and equanimity (upekkha) in the discussion of what the Buddha’s monks should or should not be eating. I’m not sure what exactly to make of that. They seem a bit out of place, so perhaps an addition by later compilers of the canon, or maybe there is a deeper purpose that simply escapes me. Perhaps, and this would be my guess: the discussion is framed around meat-eating (a physical activity) to serve as an example of what possible mental intentions might be at play, both for those eating and for those more closely responsible for the killing of animals.

* in the Āmagandha Sutta (Sutta Nipata II.2.) Kassapa refutes the view of defilement through eating meat and states that this only comes about from an evil mind and actions. This, it seems is an argument against a dogmatic clinging to vegetarianism and a restatement of the primacy of mind and mental influence upon our acts.

** One of the first things that jumped out at me regarding this sutta is that it is in the “householder group” (Gahapativaggo) in the Majjhima Nikāya (number 55, book pp.474-476). Jīvaka, after whom the sutta earns its name, is a rich householder, and the owner of the mango grove in which the Buddha is resting. In this group of suttas all are addressed to householders – some are taught by Ananda, some by the Buddha himself. All deal closely with the differing doctrines and practices of the time.