* A guest-post by C. Pierce Salguero.

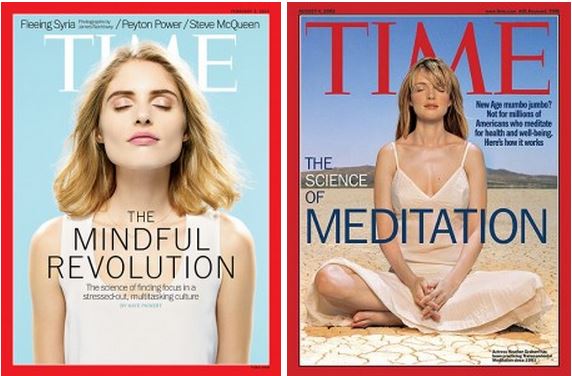

TIME magazine’s 2 Feb 2014 cover (above, left) announces the arrival of the “Mindful Revolution.” The publication joins a flurry of recent examples confirming that a shift is taking place in the representation of meditation in American popular media.

This is not the first time that meditation has been featured by TIME—a strikingly similar cover was published on 4 Aug 2003 (above, right). Compared to the 2014 cover, the earlier one is transitional. The photograph of a white, attractive, blonde woman in her thirties is a none-too-subtle argument that meditation should be considered part of the American mainstream. But, if we pay attention to the words, we see that this cover takes a defensive posture. We are told that meditation has links with “health,” “well-being,” and “science.” However, meditation’s close associations with the 70s counterculture and Asian Buddhist teachers still linger, and TIME must work to distance itself from such “New Age mumbo-jumbo.”

The more recent cover demonstrates that today meditation is unquestionably mainstream. The need to explicitly distinguish it from “mumbo-jumbo” no longer exists: there is no doubt that it is a “science” that holds the revolutionary antidote to stress. There is no doubt that it can help us develop focus while multitasking (and thus keep the gears of twenty-first century American capitalism churning). The word “meditation,” with all of its New Age and Orientalist baggage, has been dropped in favor of “mindfulness,” the prevailing lingo among scientists and a growing cadre of meditation teachers. The half-lotus seated position in the 2003 cover—all too reminiscent of the Buddhist roots of the practice—has also been removed.

One way to think about these magazine covers is as attempts to use text and visuals to “translate” an originally foreign practice, and to resituate it in the contemporary American context. As in all cases of translation, the creators of these covers made decisions about how to represent foreign knowledge, and they had at their disposal a spectrum of options for doing so. The two TIME covers both utilize highly domesticating representations of meditation, downplaying the foreignness of the practice and highlighting its compatibility with mainstream American life. What a difference a decade makes, however. While the 2003 cover’s dismissal of meditation’s Asian expressions as “mumbo-jumbo” belies a lingering anxiety over the domesticatability of meditation, the 2014 cover can collapse meditation into the totalizing rubric of science and into the no-less totalizing image of a white female sex object with nary a second thought.

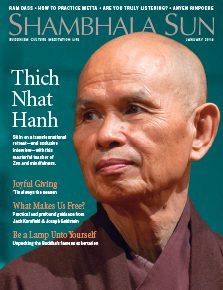

Contrast these domesticating approaches with the more foreignizing representations of meditation on the cover of the Jan 2014 issue of the Buddhist periodical Shambhala Sun, which may well have sat on a shelf alongside the second issue of TIME discussed above. The photo and name of the Vietnamese Buddhist leader Thich Nhat Hanh, the other foreign names and words strewn across the cover (Ram Dass, metta, Anyen Rinpoche), even the title of the magazine itself, all highlight the Asian origins of meditation. The magazine also makes no bones about associating meditation with Buddhism, with all of the connotations of exoticism and claims of tradition that that connection invokes for readers. Unlike TIME, which must speak to the mainstream, Shambhala Sun attracts a small but passionate minority by mobilizing foreignizing translations that appeal to an upper class readership in search of authenticity.

Contrast these domesticating approaches with the more foreignizing representations of meditation on the cover of the Jan 2014 issue of the Buddhist periodical Shambhala Sun, which may well have sat on a shelf alongside the second issue of TIME discussed above. The photo and name of the Vietnamese Buddhist leader Thich Nhat Hanh, the other foreign names and words strewn across the cover (Ram Dass, metta, Anyen Rinpoche), even the title of the magazine itself, all highlight the Asian origins of meditation. The magazine also makes no bones about associating meditation with Buddhism, with all of the connotations of exoticism and claims of tradition that that connection invokes for readers. Unlike TIME, which must speak to the mainstream, Shambhala Sun attracts a small but passionate minority by mobilizing foreignizing translations that appeal to an upper class readership in search of authenticity.

The fact that there are these radically different approaches to the representation of Buddhist meditation—and, indeed, of Buddhism more generally—in contemporary America is not surprising. In fact, varying approaches to translation are the norm whenever aspects of foreign knowledge are introduced, absorbed, or appropriated into new cultures. These different approaches are the result of variances in the preferences, ideologies, and economic interests of different groups of translators and readers.

The divergences in approaches between these magazine covers caught my eye because I have recently written a book on the very similar diversity in the representation of Buddhism during its introduction to China in the period AD 150-1000 (C. Pierce Salguero, Translating Buddhist Medicine in Medieval China. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014 [Amazon, TOC & Excerpt]). Due out this summer, this book looks at arguments being made in medieval China—as in the U.S. today—that Buddhism offered new ways of maintaining health and well-being. The book concentrates on the wide range of foreignizing and domesticating strategies employed by Chinese translators in trying to forward such arguments. Some translators preferred domesticating approaches that made Buddhism seem accessible and compatible with Chinese norms, while other preferred to highlight the foreign origin of Buddhist ideas in order to capitalize on their exoticism. These strategic approaches and the social dynamics behind them seem, in broad outlines, quite analogous to the range of efforts to place Buddhism in contemporary America.

The divergences in approaches between these magazine covers caught my eye because I have recently written a book on the very similar diversity in the representation of Buddhism during its introduction to China in the period AD 150-1000 (C. Pierce Salguero, Translating Buddhist Medicine in Medieval China. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014 [Amazon, TOC & Excerpt]). Due out this summer, this book looks at arguments being made in medieval China—as in the U.S. today—that Buddhism offered new ways of maintaining health and well-being. The book concentrates on the wide range of foreignizing and domesticating strategies employed by Chinese translators in trying to forward such arguments. Some translators preferred domesticating approaches that made Buddhism seem accessible and compatible with Chinese norms, while other preferred to highlight the foreign origin of Buddhist ideas in order to capitalize on their exoticism. These strategic approaches and the social dynamics behind them seem, in broad outlines, quite analogous to the range of efforts to place Buddhism in contemporary America.

Many Translation Studies scholars speak of their work as being “descriptive” rather than “prescriptive.” In other words, they do not analyze translations to determine which approach is better or worse, but rather to understand the underlying reasons behind why such decisions are made in particular times and places. This is my position as well. The TIME cover has come under fire for its representation of meditation, but Translation Studies reminds us that all translations without exception are intimately entangled in an array of social, cultural, and ideological influences. The TIME cover is an easy target for criticism because it utilizes the extreme domesticating end of the spectrum. In doing so, it becomes a caricature of itself and lays bare its ideological commitments. But we should not forget to critically examine all kinds of representations of Buddhism in contemporary America, especially those that seem upon first glance to be the most “authentic.”

~

C. Pierce Salguero is an interdisciplinary humanities scholar interested in the role of Buddhism in the crosscultural exchange of medical ideas. He has a Ph.D. in History of Medicine from Johns Hopkins University, and teaches Asian history, religion, and culture at Penn State University’s Abington College, located near Philadelphia. The major theme in his scholarship is the interplay between the global transmission and local reception of Buddhist knowledge about health, disease, and the body. His website is www.piercesalguero.com.