Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcha, and Tirzah: Seeking Justice

By David C. Cramer

Read Numbers 27:1–11; Psalm 82

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus offers various teachings about how to respond to others who have wronged you.

Jesus teaches that those who are persecuted are blessed because their reward is in heaven.

Jesus teaches that, if you recall that someone has something against you, you should immediately seek them out and be reconciled to them.

Jesus teaches that you shouldn’t resist an evil person but should turn the other cheek, love your enemy, and pray for your persecutor.

And finally, Jesus teaches that, if you know of someone’s sin, you should go to them privately to point out their offense and try to correct them in a face-to-face situation. Only after they refuse to listen to you should you bring another witness or two into the discussion. And only after they refuse to listen to you in the context of one or two witnesses should you make the case public before the church. (Matthew 5:10–12, 21–26, 38–48; 18:15–20)

These are all important teachings for how to deal with interpersonal conflict—especially in situations where there is a dispute between two parties that each have roughly equivalent power and status within the community.

Unfortunately, these teachings are often twisted, perverted, and misapplied to contexts where there is an imbalance of power, and an injustice has occurred. Victims of injustice or abuse are often told by church leaders that they cannot go public with their stories without first confronting their abusers face-to-face. They should seek forgiveness and reconciliation rather than justice. And, moreover, doesn’t the apostle Paul write something to the Corinthians about women staying quiet and submissive in church and asking their husbands questions at home instead of in church?

But given disparities of power, not to mention the trauma of facing one’s abuser, such council has the effect of quite literally silencing those who are abused and thereby perpetuating abuse.

The reality is that neither Jesus’s teachings nor Paul’s were ever intended to discount the pursuit of justice.

How do we know?

For starters, we know this because Jesus begins his teachings by saying that “God blesses those who hunger and thirst for justice, for they will be satisfied” (Matthew 5:6).

But beyond this, we know because we have biblical examples of some rad women who seek justice for themselves and are commended by God. They are the five sisters Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah, the daughters of Zelophehad. And their story is told in the fourth book of the Bible, the book of Numbers.

There’s no getting around the fact that ancient Hebrew society, as with most societies throughout history and today, was a deeply patriarchal society. It was organized around 12 tribes, each named after one of the sons of Israel. Each of the tribes had its own land, and that land was passed down generation after generation to the male descendants of the son.

But a man named Zelophehad had five daughters and no sons. While the Israelites were wandering in the wilderness, Zelophehad died, leaving no male descendants to claim his property.

So what did his five daughters do?

Did they just conclude that it’s OK to lose their land because they have treasures in heaven?

Did they go privately to their male relatives to express their grievances face-to-face?

Did they offer to turn the other cheek and offer their possessions in addition to their property to their male relatives?

No.

They banded together.

They filed a public petition.

And marched publicly straight to the leaders of the Israelites: Moses, Eleazar the priest, the tribal leaders, and the entire community at the entrance of the Tabernacle.

They didn’t ask Moses and the other leaders for anything.

They publicly told them what justice required: “Give us property along with the rest of our relatives” (Numbers 27:4).

Even within this deeply patriarchal society, these rad women knew they had rights, and they made those rights known publicly for all to see and hear.

To his credit, Moses takes up their cause with the Lord.

And the Lord vindicates these five sisters: “The claim of the daughters of Zelophehad is legitimate. You must give them a grant of land along with their father’s relatives. Assign them the property that would have been given to their father” (Numbers 27:7).

God then adjusts inheritance law to include not only sons but also daughters. Because these rad women were fiercely faithful in their pursuit of justice, God is not only fiercely faithful to them in return. God also uses their case to create a more just and equitable society for all.

So, yes, if you have an interpersonal dispute with someone of relatively equal power as you, it is still good to take that up with them privately first to try to settle the matter one-on-one.

But the good news of the story of Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah is this: If you are the victim of abuse or injustice, you can band together with advocates and declare your case publicly, and God will vindicate you. Moreover, by bringing such abuse or injustice to light, you can be the spark that leads to justice for others as well.

While there are likely people here today in the shoes of these five sisters, many of us also find ourselves more in the shoes of Moses. We have benefitted from injustice ourselves and, like Moses, we need to be attentive to hear the stories of those who have been wronged.

One of those stories, as with this story in Numbers, has to do with property. Our church may soon be facing a dispute with our former district over our church properties. We hope it doesn’t come to that, but if it does, we are prepared to defend our rights publicly like these five daughters.

But the reality is that the land we worship on is neither the church’s nor the district’s. Long before any of us were here, the land we are on today was inhabited and stewarded by Indigenous peoples. Indeed, the land on which we worship is land of the Potawatomi Nation.

When settlers first arrived in Northern Indiana, they made treaties with Indigenous people who were already here. But under the presidency of Andrew Jackson, the US government instituted a policy of Indian removal. On May 28, 1830, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, passed by the US congress, which led to forcible removal of Indigenous people from their ancestral land so it could be settled by white settlers.

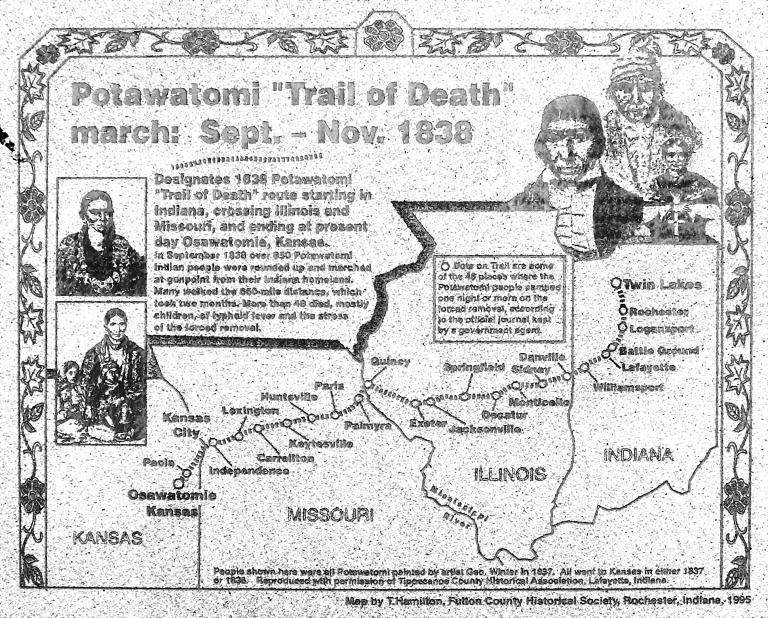

As I have described before, in 1838, under the following president, Martin Van Buren, around 800 Potawatomi were marched at gunpoint by US soldiers from Northern Indiana to Kansas on what became known as the Trail of Death. It is called the Trail of Death because, during this forced emigration in the chilly months of September and November, an estimated 60 of the 800 Potawatomi—most of them elderly or children—died. Those who survived were left homeless and landless, and many of them eventually moved south to Oklahoma.

As a congregation of predominantly white descendants of these settlers, we are the beneficiaries of these injustices and atrocities.

And this isn’t just 200-year-old history.

The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi were the only band to gain permission to remain in Southern Michigan and Northern Indiana during the period of forcible removal. And they have been among us as neighbors ever since, although they only regained federal recognition by the US government in 1994. And, on November 18, 2016, the band received back 166 acres of land in trust right here in South Bend.

In addition to being our neighbors, many of the Pokagon Band are also our family in Christ, having adopted the Christian faith of the early settlers.

As we seek the peace of our neighborhood by sharing God’s love with our neighbors, it is our responsibility to learn these stories of our neighbors and siblings. And it is our responsibility to ask the Lord what justice requires of us.

A first small step in that process is acknowledging that this land is not our land and repenting of the injustices of our ancestors from which we still benefit.

The next and more difficult step is to discern together what faithfulness entails in light of the injustices from which we benefit.

But as we acknowledge our own unfaithfulness, we know that God remains fiercely faithful, for God cannot deny who God is (2 Timothy 2:13).