Since the attacks of September 11, 2001, I have had doubts about the way in which the lens of nationalism informs my view of the world. While many turned to the flag and the chapel in the aftermath of those attacks, both seemed superficial to me. The loss that day was not an American loss but a loss of humanity. Those lives had value not as Americans (of course, many were not Americans), but as human beings. That many rallied around the banner of patriotism disturbed me then as much then as it does today. To identify life with nationality seems to cheapen life.

My disposition towards patriotism and nationalism led me to approach Martha Nussbaum’s argument for cosmopolitanism in For Love of Country: Debating the Limits of Patriotism with a sense of hope. Nussbaum’s argument is not itself a response to September 11 (since it appears five years earlier) but is instead a call for a new outlook in the age of globalization when we no longer can think of ourselves as strictly local actors. As Americans, we seem to often view the world as our background but at the same time limit our view of the world to those things that are within our own national interest. For Americans this is often the case because of our relative strength, wealth, and cultural influence. But this ease by which we view the world from either a nationalistic or realist point of view is troubling from a moral point of view.

In this post, I will look at Nussbaum’s argument for cosmopolitanism as an alternative to patriotism. After placing Nussbaum’s argument within the larger debate about cosmopolitanism, I will look at a number of critiques of her argument.

I will argue for a form of strong moral cosmopolitanism. I argue that this position is more morally justifiable that patriotism. I will also argue for moral cosmopolitanism over political cosmopolitanism. The purpose of this post is to provide an argument for cosmopolitanism in general and strong moral cosmopolitanism in particular.

<!–more–>

Nussbaum on Cosmopolitanism

For Nussbaum, the cosmopolitan is a “person whose allegiance is to the worldwide community of human beings.” This is a person who sees herself as a citizen of a global community of human beings rather than a citizen of a specific nation-state. Now this does not mean that they do not have citizenship, of a legal sort, in an actual nation-state, but instead means that they view their moral and sentimental allegiances as stretching beyond the political boundaries of the nation-state. In this context, citizenship is not a matter of legal membership but moral membership. It is not the content of our passport but the content of our moral obligation.

Nussbaum presents her argument about cosmopolitanism against the backdrop of a discussion by philosopher Richard Rorty and historian Sheldon Hackney about “American identity” and “national pride.” What Nussbaum, and cosmopolitans in general, invite us to do is to consider whether we should even be having discussions about the nature of national indentify and patriotism. Instead, we need to be discussing whether such a limited scope is sufficient, particularly in a world which is so heavily define by globalization. This is due to the cosmopolitan concern that patriotism and other forms of national identity lead us to forget the problems and needs of those beyond our own borders.

For Nussbaum, patriotism and cosmopolitanism are both socially constructed concepts. We are socialized to view the world through a particular lens, whether that lens is tribal, regional, national, or global. For this reason, Nussbaum asks us to consider how we are to educate our children and grandchildren. She asks if it is “sufficient for them to learn that they are above all citizens of the United States but that they ought to respect basic human rights of citizens of India, Bolivia, Nigeria, and Norway?” For Nussbaum, this approach does not sufficiently ingrain the basis for a sincere respect of those other peoples. Instead she argues that students need to “learn a good deal more than they frequently do about the rest of the world in which they live, about India and Bolivia and Nigeria and Norway and their histories, problems, and comparative successes.” Yet this is not merely an argument for a comparative study of world cultures but instead an argument about how we approach and view those cultures and people. Nussbaum asks us, whether our children “should be instead taught that they are, above all, citizens of a world of human beings, and that, while we happen to be situated in the United States, they have to share this world with the citizens of other countries?” This question is more of a challenge than a question. It also shows the radical nature of cosmopolitanism. While this argument seems friendly to my ears, it challenges some of the strongest and deepest sentiment that one has towards their own nation. While these sentiments are problematic to me, they are the ones which many seem unlikely to challenge, let alone throw them off. For this reason, Nussbaum says that to be cosmopolitan, is to be lonely.

The Genealogy of Cosmopolitanism

Cosmopolitanism has its roots in ancient political thought. Nussbaum draws her motto for cosmopolitanism from the Cynic Diogenes who stated “I am a citizen of the world.” The earliest arguments for cosmopolitanism, as well as the term itself, comes from the Stoics. Nussbaum wraps her argument within this Greek tradition, by not only adopting its stance of cosmopolitanism but also by adopting its Stoic attitude. According to Nussbaum, the Stoics felt “that we should give our first allegiance to no mere form of government, no temporal power, but to the moral community made up by the humanity of all human beings.” Stoic cosmopolitanism centers on three ideas, contends Nussbaum. First, we need to fully understand humanity as a whole before we can achieve “self-knowledge.” By limiting our knowledge to our particular tribe or nationality we fail to understand ourselves because we do not fully understand what it means for us to be human. Second, the Stoics recognized that “faction” and “partisan loyalties” undermine political deliberation and only “by making our fundamental allegiance to the world community of justice and reason do we avoid these dangers.” Third, Stoics preferred cosmopolitanism over local allegiance because they recognized that humans deserved respect and dignity because of their ability to reason.

While the Stoics are a possible source of cosmopolitanism, they are not a particularly good foundation for the type of cosmopolitanism that I envision. One reason for this is that Stoics generally are not arguing for a different politics but instead a rejection of politics. The heart of Stoicism is the idea that the only thing which we can change is our attitude towards the world around us. It we are to apply this to approach to global poverty, it does not seem that we would seeks solutions, let alone bring about those solutions, if we adopt Stoicism. Thomas Pangle draws on Cicero’s critique of the early Stoics to say that they failed to understand and appreciate the value and significance of patriotism, a critique of Nussbaum that we will look at later. However, Pangle points out that while many cosmopolitans make reference to the Stoics, it is not the Stoics but Immanuel Kant who is the root of many contemporary arguments about cosmopolitanism.

While, Kant’s theory of international relations places hope in the prospect of a peace between democratic republics that is maintained and secured by a League of Nations, his larger moral theory contributes significantly to the concept of cosmopolitanism. Particularly, Kant’s second formulation of the categorical imperative promotes the human focus of Nussbaum’s style of cosmopolitanism. The second formulation says that we should always act in accordance with the principle that humans are always ends and therefore should never be treated as a means. This principle, known as the humanity as an ends principle, direct us to always treat human beings with dignity and respect strictly based on the fact that they are human beings. We cannot make distinctions between humans and it would be even worse if we would make such distinctions on the basis of sentimental patriotism given that Kant demands that moral decisions be made based on reasoned principles and not inclination or sentiment. This emphasis on moral principle over common sentiment reinforces the idea that if we are to respect human beings we must respect all human beings, whether they be those that live within the same nation-state as myself or those beyond familiar borders.

Kantian ethics is surely not the only possible basis for a cosmopolitan perspective. Utilitarianism is committed to the philosophical principles of impartiality and equality which demand that we consider the happiness of all human beings. We cannot, according to utilitarianism, consider the happiness of some people as being of greater significance than the happiness of others. As a result, considering the happiness of one’s compatriots above that of other living beyond our own national borders would be inconsistent with the principle of impartiality.

The utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer made one of the earliest contributions to the contemporary discussion about global justice. Singer argues that we have a moral obligation to do what we can (and we can do something) to alleviate the suffering of those plagued by famine and poverty in the poorest areas and nations of the world. His argument relies heavily on the image of a young child drowning in a pond. If one were to witness such a scene one would clearly have an obligation to wade in to the water and pull the child out of harm’s way. For Singer, our knowledge of the suffering and death in parts of the third world is no different than us being aware of the child in the pond and we must act.

Singer’s essay in many ways stands out because it was one of the few attempts to formulate a philosophical argument, whether moral or political, about global issues at a time when political philosophy was dominated by John Rawls’ argument about the just state. Rawls limits his theory of social justice to a closed political community within specific political boundaries. He does not deny global justice but leaves the question of international obligation for future consideration. This exclusion draws criticism from some of his earliest critics. Yet the question was left largely unaddressed for two decades. Two thinkers, Charles Beitz and Thomas Pogge, sought to apply the major elements of Rawls’ theory, including the original position, the veil of ignorance, and the two principles of justice, to a global scale. Both Beitz and Pogge assumed that, while Rawls did not address a scheme of international distributive justice, his principles were adequate for the challenge of taking on issues of global justice.

The cosmopolitan Rawlsian project was complicated by the fact that John Rawls himself rejected cosmopolitanism when he developed his own theory of international relations. Instead, in a manner similar to Kant, Rawls proposed a theory focused on the relationship between states rather than one focused on obligations between the individuals of the world. Specifically he rejected the idea of a global difference principle as going beyond what he viewed as part of his realistic utopia. Yet, Rawls’ theory could be viewed in some sense as cosmopolitan in that it rejects realism and draws special attention to the world order as an equal concern with the domestic order. But it this falls short of the cosmopolitan arguments offered by Nussbaum, Pogge, and Beitz. Rawls’ argument left Allen Buchanan to wonder whether Rawls was stuck in a Westphalian world in a post-Westphalian age. In other words, was Rawls unable to look beyond the world as it was familiar to him, a world of competing nation-states rooted in the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, a world which many feel is now behind us. Cosmopolitans tend to think that it is an outdate view.

Critiques of Cosmopolitanism

While cosmopolitans like Nussbaum and myself find our position as almost second nature, this is clearly not the case for many people. Patriotism, whether it be a philosophical perspective or a traditional sentiment, is amongst the most deeply held and cherished positions. Yet, this is not to say that critics of cosmopolitanism are simple souls to be dismissed.

Benjamin Barber and Michael McConnell provide defenses of patriotism and local allegiances. Barber argues that the issue should not be view as a dispute between patriotism and cosmopolitanism, but instead a dispute about the nature of patriotism. There is a form of patriotism which is bad. However, there is also a positive form of patriotism and Barber feels that this type of patriotism is good for democracy and should be encouraged.

Jon Mandle describes two models of nationalism which is valuable in considering the merits of patriotism. Particular nationalism is the idea that a nation is “specially chosen and valuable from a moral point of view itself.” This type of patriotism places ones nation in a superior position to others. Generalized nationalism, on the other hand, recognizes that people give a certain moral weight to their own nation and people. That we have affinities for our own country and countrymen is understandable and reasonable given the way in which we view and experience the world around us. Particular nationalism is not defendable in that it violates all basic senses of human equality.

American patriotism, which is the type of patriotism that Nussbaum has in mind, can be viewed as a bright example of positive patriotism, Barber argues. He says that American patriotism is rooted in a commitment to constitutional democracy and the principles of liberty and equality. This is different from forms of patriotism that are rooted in religious or ethni c identities. In the United States it is easier to adopt a patriotism that transcends ethnic, tribal, and ethnic loyalties because of our size and diversity. Now, this is not to say that American patriotism cannot take ugly forms for it surely does. But rather than give up on patriotism, Barber says, we need to build up the positive forms of patriotism and fight against those which are destructive to the “civic patriotism” which Barber proposes.

Michael McConnell argues that both arguments for nationalism and cosmopolitanism miss the point. Rather than expanding our view beyond the nation-state to humanity as a whole, we need to look a little closer to home. McConnell calls Nussbaum back to her Aristotelian roots, by reminding her that Aristotles ideal level of allegiance was the city-state. Drawing on Edmund Burke’s “little platoons,” McConnell, posits that these local associations, quoting Burke, are “the first link in the series by which we proceed toward a love to our country and to mankind.” Without a strong sense of attachment or commitment to our neighbors we will not develop the moral sensibilities to become either a patriot or a cosmopolitan. It is through the interactions we have with family members and community members that we learn the respect for other humans that is need to have a Kantian respect of human dignity, according to McConnell. Now Nussbaum acknowledges that we have allegiances to a variety of “concentric circles,” starting with the self, immediate family, extended family, and neighborhood, and ranging out to fellow city-dwellers, fellow countrymen, and ultimately “humanity as a whole.” Yet, Nussbaum views these smaller circles as all sub-divisions of humanity and not humanity as a collective of little platoons or neighborhoods. In the way that Aristotle values the city-state over the village, family, and individual, Nussbaum places humanity above the smaller concentric circles. For McConnell, we need to give greater emphasis on those smallest and closest circles.

One line of critique does not think that cosmopolitanism necessarily is the cure to the ills which Nussbaum thinks. These types of criticism are important because it is easy for cosmopolitans to get caught up in the clouds (or the cosmos) about the wonderful prospect of a more cosmopolitan world. Richard Falk points out that globalization is in some sense a form of cosmopolitanism. Yet, while globalization has broken down national borders in terms of culture and economics, it is hard to say that these changes are positive ones from the perspective of human dignity. Falk points to NAFTA, GATT, and the WTO as cosmopolitan enterprises which have violated “social-democratic” principles or equality and human well-being. For Falk the primary problem with the argument presented by Nussbaum is the “implicit encouragement of a polarized either/or view of the tension between national and cosmopolitan consciousness.” Must we choose? This is a good question, which Amy Gutmann takes on. For her, there is not a need to choose between an allegiance to the nation-state or a world-wide community of human beings because our allegiance should not be rooted in geographical terms, but rather couched in terms of an allegiance to “the moral importance of being empowered as free and equal citizens of a genuinely democratic polity.” Gutmann’s primary challenge to cosmopolitanism is that the concept of “citizens of the world” requires a community of humans world-wide. There is no such community, Gutmann says and we “can truly be citizens of the world only if there is a world polity.”

The issue of a world state makes the debate over cosmopolitanism a bit messy. Nussbaum insists that her argument is not one for a world government but instead for a global moral perspective. Gutmann’s question then is how do we develop such a moral perspective without a world government? For Nussbaum the primary requirement is a change in the way that we socialize and educate our children. Granted, this is not simple undertaking. Yet, other argue that if cosmopolitanism is to be realized then a world government would be desirable.

Strong Moral Cosmopolitanism

We can see from the many critiques of Nussbaum’s concept of cosmopolitanism that an argument for cosmopolitanism requires specific parameters. That an argument is cosmopolitan does not make it a sound one. The first distinction that I would like to make is the difference between moral and political cosmopolitanism. Moral cosmopolitanism states that we have an obligation to all human beings whether they are compatriots or foreigners. Political cosmopolitanism seeks to establish world-wide political institutions with hope of bringing about a unified community of human beings. Nussbaum’s cosmopolitanism appears to be a form of moral cosmopolitanism, though her lack of clarity on this distinction seems to cause some confusion.

I strongly prefer moral cosmopolitanism. The reason for this is that I do not see a world state as necessary for achieving a just global order. Additionally, moral cosmopolitanism recognizes that one can argue for the respect of human dignity without a world state. It is that respect for human dignity that is the end of our enterprise and not any particular governmental structure. It must be said, that while my theory does not require a world state, I am less opposed to the idea than a strong nationalist would be. I would assume that most strong nationalists would oppose moral cosmopolitanism because they would view it as a slippery slope towards world government.

As a moral cosmopolitan, I do sustain and seek to affirm international institutions such as the United Nations. In fact, I think that the United Nations should take a more active role in the protecting the principles found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. I am skeptical about the extent to which nations, particularly the five permanent members of the Security Council, can use the United Nations to advance their own interests rather than the good of humanity. Yet, I do not think that the United Nations requires greater coercive power but instead that it should function under more democratic and egalitarian ground rules. Americans would likely ask why they would want to belong to the United Nations if they would have less control that they do today. In this sense, as a cosmopolitan, I do not view the United Nations though the lens of national interest but instead human interest. While Nussbaum create a two-sides argument between cosmopolitans and patriots, cosmopolitanism is equally an argument against realism and the international politics of amoral interest.

Additionally, as a moral cosmopolitan, I do not value international institutions merely because they are international but rather to the extent that they promote just conditions. In this way, I agree with Richard Falk that many global institution merely extend the inequalities of capitalism to a global scale.

I do view the nation-state as an important and necessary institution. This may sound odd as part of a cosmopolitan argument, but that does not have to be the case. What I mean by this is that nation-states are important in that they offer the protection of the state to individuals in a way that can be responsive to the unique cultural, geographical, and climate demands of a given region. We view states that fail to offer this protection with concern. In addition to protection, the nation-state is also an effective means of providing services such as educational and health services. Importantly, the nation-state also provides the possibility of strong mechanisms for distributive justice.

The difference between the moral cosmopolitan and the nationalist is that I view the nation-state as important, but mine is no more important or better that other nation-states. Now such claims are clearly not the basis of holiday parades. However, as a cosmopolitan my interest in the nation-state is the extent to which they secure justice for individuals. So while I fight for equality and proclaim justice in my own country, I support efforts to obtain equality and justice in other countries. Additionally as a moral cosmopolitan I reject policies which harm other peoples in the name of nation interest. Quite disturbing are the actions of the United States during the Cold War, when my own government sacrificed the human rights, democracy, and well-being of other people in the name of American national interest. Of course, such Utilitarian calculations are very disturbing to a Rawlsian and I doubt that Utilitarianism would be satisfied either.

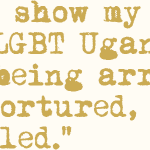

In many ways, while John Rawls stops short of adopting cosmopolitanism, my own cosmopolitan disposition is very much shaped by his theory of justice as fairness. Particularly, Rawls rejects the idea that we deserve the positive or negative situations that come to us as a result of our birth. Such things as natural talents and wealth are morally arbitrary to Rawls because we are born into them. We do not deserve, in a moral sense, either the good fortune or bad fortune. It seems that our place of birth likewise is morally arbitrary. I had nothing to do with the fact that I was born into a middle class family in the United States and a poor Ugandan had nothing to do with the fact that she was born poor in a poor developing country. If we can dismiss claims of desert related to wealth in these cases, why not also reject possible claim of desert based on nationality. Clearly, in comparing me with the Ugandan women, it is not only my wealth privilege but also my existence in a more peaceful and resource strong nation that increase my chances for an autonomous life. So while I am lucky, I do not write her off as unlucky but instead seek to improve her condition and therefore her prospect for autonomy. While such a task is difficult and complicated, the purpose of this paper is not to discuss the proper means of development (other than to say that it must be just) but to strongly state that such an obligation does have claim upon me and my nation.

Now I am not just a moral cosmopolitan but a strong moral cosmopolitan. I make a distinction between a strong and a weak version of cosmopolitan based on the type of obligation that springs from that model. A weak moral cosmopolitan recognizes that they should not cause harm to other people out of individual or national interest. Yet, their obligation is limited to not causing harm. As long as no harm is done, the obligation is fulfilled. A strong moral cosmopolitan argues that beyond not causing harm, one must seek to improve the conditions of others around the world, both within my own nation-state and elsewhere. This obligation is a positive obligation. While I am also restricted from doing harm, I must also do good. As a Kantian and a cosmopolitan, I recognize that others will have different ends from myself and that there desired conditions will vary from locale to locale. Here is where the demand of Rawls’s difference principle or other conceptions of global justice and global ethics comes into play. However, I will leave those details for a different time and place.

Conclusion

In looking at cosmopolitanism, we can see that it is a complex and possibly confusing position. It is without many of the comforts of patriotism. Additionally, moral cosmopolitanism does not seek to establish an institutional home and thereby further adds to the loneliness that Martha Nussbaum warns comes with cosmopolitanism. Yet, it is the morally correct position to take. Is it a perfect position? I am not ready to say. However, for me it is the only morally consistent stance to take in light of the claims of patriotism.

While cosmopolitanism may not bring me sentimental comfort in the post-9/11 era, it does bring a comfort of conscience.

References

Barber, B. (1996). Constitutional Faith in For love of country : Debating the limits of patriotism. Nussbaum, M. C., & Cohen, J. eds. Boston: Beacon Press.

Barry, B. M. (1973). The Liberal Theory of Justice; a Critical Examination of the Principal Doctrines in A Theory of Justice by John Rawls. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Beitz, C. R. (1999). Political Theory and International Relations. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Buchanan, A. (2000). Rawls’s Law of Peoples: Rules for a Vanished Westphalian World. Ethics, 110(4), 697-721.

Cabrera, L. (2004). Political Theory of Global Justice : A Cosmopolitan Case for the World State. London ; New York, NY: Routledge.

Dallmayr, F. (2003). Cosmopolitanism: Moral and Political. Political Theory, 31(3), 421-442.

Falk, R. (1996). Revisioning Cosmopolitanism in For Love of Country : Debating the Limits of Patriotism. Nussbaum, M. C., & Cohen, J. eds. Boston: Beacon Press.

Gutmann, A. (1996). Democratic Citizenship in For Love of Country : Debating the Limits of Patriotism. Nussbaum, M. C., & Cohen, J. eds. Boston: Beacon Press.

Harris, H. (1927). The Greek Origins of the Idea of Cosmopolitanism. International Journal of Ethics, 38(1), 1-10.

Kant, I. (1957 [1795]). Perpetual Peace. New York: Liberal Arts Press.

Kant, I. (1991 [1785]). The Metaphysics of Morals. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mandle, J. (2006). Global Justice. Cambridge ; Malden, MA: Polity.

McConnell, M. (1996). Don’t Neglect the Little Platoons in For Love of Country : Debating the Limits of Patriotism. Nussbaum, M. C., & Cohen, J. eds. Boston: Beacon Press.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2000). Symposium on Cosmopolitanism Duties of Justice, Duties of Material Aid: Cicero’s Problematic Legacy. Journal of Political Philosophy, 8(2), 176.

Nussbaum, M. C., & Cohen, J. (1996). For Love of Country : Debating the Limits of Patriotism. Boston: Beacon Press.

Gutmann, A. (1996). Democratic Citizenship in For Love of Country : Debating the Limits of Patriotism. Nussbaum, M. C., & Cohen, J. eds. Boston: Beacon Press.

Pangle, T. L. (1998). Socratic Cosmopolitanism: Cicero’s Critique and Transformation of the Stoic Ideal. Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue canadienne de science politique, 31(2), 235-262.

Pogge, T. W. (1992). Cosmopolitanism and Sovereignty. Ethics, 103(1), 48-75.

Pogge, T. W. M. (1989). Realizing Rawls. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Rawls, J. (1971). A Theory of justice. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. (1999). The Law of Peoples. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Singer, P. (1972). Famine, Affluence, and Morality. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 1(3), 229-243.