Love sucks.

To love is to desire communion with the beloved, to ache for unity, oneness, and a coming-together. But my beloved is infinitely not me, just as I am infinitely not her. Love seeks to bring me and not-me into one, that the “two become one flesh”, that “we’ll be one tonight,” that “you’ll be in my heart” that “I’ll melt with you,” “lose myself” and on and on, a heaving tumble of ill-thought love-songs and poorly-constructed sonnets that lie to our hopeful faces.

How can the two be one, when “two” is by definition not “one”? How can I love my beloved to the point of total unity? Love seems a lot like a sham diet-plan espoused on late-night TV: Everyone talks about it, everyone wants its boldly proclaimed results, but there is not a human alive who can claim to have achieved what it urges us to achieve — communion.

After all, no lovers would say, “We are finished with our project of love.” No friends love each other to the point of complete communion.

If we were one with our beloved we’d no more divorce her than kill ourselves. If we were one with our friends, to hate them would be suicide. If we loved our children as ourselves, then our abuse would only ever be a self-maiming — we’d avoid it like we avoid running cheese-graters across our foreheads.

But we don’t. We fail to love quite happily, suffering little remorse and far less repentance. How often the tearing asunder of two that are one flesh is called a freedom! But actually, I understand the feeling. For if love is impossible, the end of love is a relief. Who would wish to forever follow the carrot of complete communion, the ever sought and never attained? Far better to play video games and drink Yeungling.

Unless the point of love is not the attaining, but the strive itself.

The desire that seeks to unite two infinitely separate subjects must be an infinite desire, and the passionate work of bringing her and I into communion must be an infinite work. Why else would love tend towards rash promises of forever and ever? If love was an attaining — that is, if the project of communion could be completed — all we would need to say is “I’ll love you until we are one.”

But we don’t. We know oneness is unattainable. All we can do is infinitely strive for it. Thus we promise to love forever, because only an infinite time can bridge an infinite distance. Love must be an infinite act, that is, an act acted every moment of our lives, or it is not love. Love is reach. Love is strive. Love is a dissatisfaction more satisfying than any worldly satisfaction.

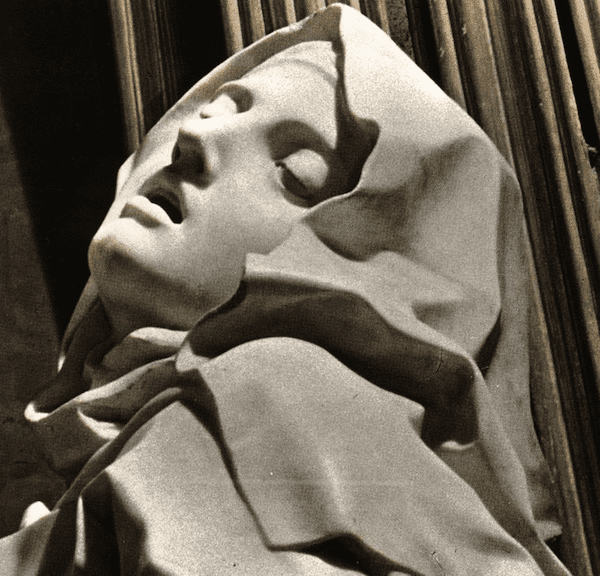

And so love is accompanied by the strangest of facial expressions and the most awkward of noises — the groan, the moan, the gasp, the screwed-up face, the tears, the ah! and the oh! These are not the blossoms of attainment, these are the sufferings of an infinite strive. The face of love seems caught between pleasure and pain, because love is not a thing achieved, but a heroic tug against impossibility, a herculean pull of infinite separation into communion. Who would not moan in such a self-destroying stretch? The lover does not hold equality with his beloved as something to be grasped at, rather he empties himself, taking the form of a slave, a slave who freely goes about the work of love without relief, for relief would mean the end of love.

Sex is the sacramentalized, incarnational expression of the erotic. Its sounds are but the sounds of love brought to a boil, and the aching mix of pleasure and pain should not be limited to its bliss. The sounds, faces, and feelings of strive are present in all love, in the coos of the mother to her child, in the cry of the child for his father, the reunification of friends, and — perhaps above all — in the face of worship.

To be in love is to be ever on the brink of metaphorical orgasm, ever before the finish-line, the communion so madly desired precisely what we will never have, yet precisely what we pant after every day of our lives. Thus love — contrary to its description in American media and politics — is absurdly difficult, hard as being punched in the face. It is a race that requires an infinite effort with no earthly hope of satisfaction. It is uncomfortable, which is perfect, for we were not made for comfort, but for infinity.

Sorry, that sounded Christian. Perhaps we are not made for infinity. Perhaps death is the end of love, because death is the end of existence. In this case, love is a disappointment, a coming closer and closer until the two are done utterly apart. Without eternal life, the desire for communion is an absurdity, a thing never fulfilled, only suffered. If this is the case — which I concede it very well may be — I return my ticket. Love can piss off. Abuse seems a far kinder dish to ladle out than a death-match of no resolution.

But maybe death is not the end of love. Maybe death is the orgasm. This pulls our language into play in a fascinating way, for the word for orgasm in French is la petite mort, literally the little death. We used to have an English equivalent: To die was to orgasm, which lead to the wonderful double-entendre in Much Ado About Nothing, when Benedick says to Beatrice, “I will live in thy heart, die in thy lap, and be buried in thy eyes,” or when John Donne, in The Canonization, puns away:

Call us what you will, we are made such by love.

Call her one, me another fly,

We are tapers too, and at our own cost die,

And we in us find the eagle and the dove.

The phoenix riddle hath more wit

By us ; we two being one, are it.

So to one neutral thing both sexes fit.

We die and rise the same, and prove

Mysterious by this love.

The synonymity of death and orgasm clarifies the Christian conception of Eternity. Eternal life is not simply a reward for good behavior, nor a purely theological concept. Eternity is precisely what we are oriented towards when we strive infinitely for communion with the beloved, and death, when it comes, is the doorway to that oneness, the final gasp and the shudder of relief as me and not-me come crashing into one.

Our “going to Heaven” is the consequence of our infinite act of love. “We know that we have passed out of death into life, because we love our brothers,” that is, because we apply ourself infinitely to infinity, making a pact with eternity by promising to love “forever” even when we have no assurance of “forever” in finite existence.

For the Christian, Death is not the death-toll ending a doomed attempt at communion — it is the orgasm and the victory of Love, the dawn by whose light our striving breaks away into eternal depths of peace, and our infinite efforts towards communion find fulfillment and repose in — where else? — infinity. Les Miserables ends with the cry, “To love another person is to see the face of God,” and it occurs to me that this is more than sentiment. If you want to orient your being towards Eternity, that is, if you want to believe in God, love.