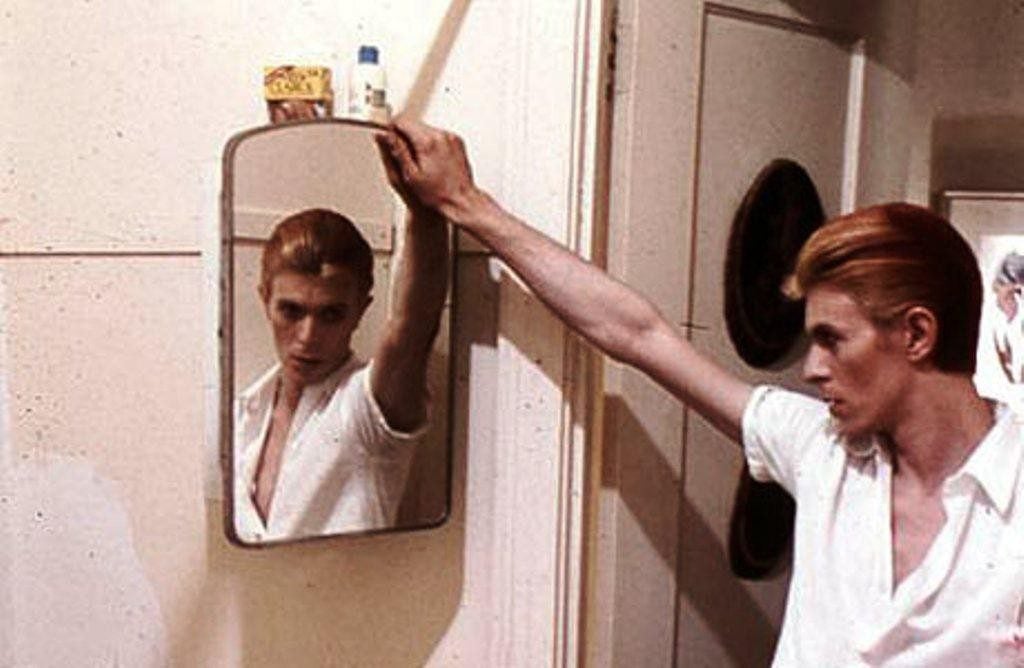

You cannot see your face. You can look into a mirror, but a mirror can only give a mirror-image. You can take a photograph, but your photograph is flat.

Besides, quantum theory applies to faces: The physicist only sees the position the electron takes as a result of its being measured. The mirrored-man only sees the position his face takes as a result of being placed in front of a mirror. The moment you step away from the selfie or the navel-gazing session, the image you gained becomes irrelevant. You pose (from pausere, “to pause, halt”) — “halting” the flow of life to look at yourself. You never know how you look when life resumes its flow — when you are grinding coffee or taking a nap.

How can we know that we are beautiful? We could practice the herculean effort to always maintain our camera-face, forever pursing our lips or raising our eyebrows, “simmering” at the universe as is custom among tribes native to the American High School — but this is guesswork. We may be ugly after all. It only takes a small slip to make a mirror-arranged sexy-face look stupid, and if the phenomenon of the duck-face tells us anything, it is this: we can be wrong, dreadfully wrong, about how good we look.

Candid photos and secret videos — while they do manage to “catch us” without pose — are inadequate. If someone sneaks a photo of us, and we look good, we are pleased. But we do not go forth in confidence, having seen the evidence, knowing, now, that we are beautiful. Our confidence fades the moment we look away from the pixels. Our body now is not our body then. The body is a body-in-time. It is known, not in snapshots or segments, but continuously. It is no surprise then, that people awash with the evidence of a thousand beautiful selfies are usually the most insecure. Since the image can only show what has been, no image can satisfy — we do not desire to have been beautiful, but to be beautiful.

Men are often shocked to find that female insecurity and vanity has extremely little to do with how a woman actually looks. Girls deemed gorgeous fret as much over their face as girls deemed plain. But how could it be otherwise, when the inability to know whether or not one is beautiful is a universal incapacity of a creature with eyes set firmly in her head? Campaigns encouraging women to affirm themselves via some reflection are misguided. We cannot affirm ourselves, because we cannot see the self we are supposed to affirm. Taking a filterless, makeup-free picture of ourselves cannot show us how we look — it can only show us how we looked at a camera in the past.

In an age of self-reflection the suggestion that we cannot know what we look like might seem absurd, but it is true: My body is not my own. My neighbor keeps it. Only he can see my body as it is in act, through time, and not merely in pose. Only he can give me the sufficient evidence to justify the proposition “I am beautiful.” Only other people can see my face.

My answer, then, to an age of insecurity and self-hatred, is a pessimistic one: There is no easy way out of the abased, shameful and insecure hole we have laid our bodies in. No number of self-affirming songs, hours spent in front of the mirror, selfies or videos can ever amount to a single moment in which we are secure in our bodies. Our bodies are secured by the eyes of our neighbors. If we are not kept there, we have no second home.

The more common answer, however, is also the more optimistic: We can become individually certain of our own beauty. We can affirm ourselves. We have the technology. We don’t need other people. We don’t need no man. The duty of the community to keep each other’s bodies has become the duty of the individual to keep his own.

Underneath a veneer of peppy self-affirmation, this task is something of an impossible mandate: You are beautiful, says Katy Perry, without having seen you. I am beautiful, you must agree, without having seen yourself. But our insecurities cannot be healed by bursts of individuality when they are a direct result of the destruction of community. Our fashionable self-affirmations do not represent a greater awareness of our individual worth, a greater liberation, or a greater acceptance of “all kinds of bodies.” They represents the attempt to fill in the pit left by strong local communities. How can we know that we are beautiful when the only source of this knowledge — the eyes of other people who see us — is increasingly distant?

Divorce, absentee parenthood, the shrunken family size, the transition of all human beings into commuters who leave their homes for work, play, food, and religion; the constant advertisement of a global market, which offers us the posed and altered bodies of people we don’t know as our models of beauty in place of the mothers, fathers, sisters, and brothers that we do — through all of this, the look of love grows rare. As we try to live according to the demands of this placeless economy, we inevitably see less faces and more pixels: Learning becomes online-learning, and the faces of family are FaceTimed. Everything from business decisions to philosophical propositions are increasingly discerned and decided in “conferences” of two-by-two squares. Technology annihilates the miles between us by allowing us to converse via images, but since an image is not a face, and a pixel is not a body, every joy of online communication is shadowed by an online insecurity, a debt of fear quietly collecting interest — that we are not seen.

In 2014, The Daily Mail reported that a young man, before he attempted suicide, took two hundred pictures of himself a day. He sought a perfect pose. He worked to see himself beautiful. When he could not, he gave testimony to the logic of individualism, which counts the inability to know we are beautiful, not as a failure of community, but as a failure of individual power, self-assertion, self-respect, self-love, self-confidence and pride. He was supposed to love himself. Didn’t he listen to Katy Perry? Didn’t he watch the Dove commercials? How could he have remained incapable of dredging up his own body and cherishing it in a moment of self-reflection? He failed the contemporary task of individualism and punished himself for it. Technology put the power of self-affirmation in his pocket, making it his fault that he remained unable to believe himself beautiful.

No artifice of technology or heroic heave of self-help can change the nature of our bodies — which is to be communal, given over to the world, and vulnerable. The turn to individual self-affirmation simply puts more power in the hands of the industries and experts who provide us with the tools we must use to pretend that we can see our own face — and like it too. The answer to corporate-sponsored idealized beauty is not a corporate-sponsored “natural” beauty. Every multi-million dollar cosmetic or clothing company supports the “real you” now — they sell you it through cell phones and surgeries, clothing and cosmetics, diets, dyes, and the constant image of beautiful people who have managed to be their “real selves” for you to look up to. No, we will not free ourselves from crumbling under the weight of an ideal beauty by introducing a newer, natural ideal — available at a brand new price. We will kick the yoke of the corporate class by ignoring them and building up the small communities they have destroyed.

We overcome the paralysis of envy, vanity, and profound insecurity over our bodies by limiting the affirmation of beauty to its genuine source — the eyes of the people who see us. It’s neighbors that we need, not giant industries, to feel comfortable leaving the house. We must disavow the vague hope for some objective, disinterested affirmation from the world out there, and consent to the logic of community, which says that it is familiarity and affection for person’s that unveils the truth about them — not the “objectivity” of a general “world.” When a husband tells his wife, “you are beautiful,” it is a perverse construction that has her think, “Yes, you think that, but the ‘real world’ may not.” When a father tells his daughter that she is beautiful, she must take his love for her as an insight born out of care-filled study — an insight that no pop-star, no matter how sincere his general affirmation to a faceless crowd, can make. We must trust our communities to tell us about ourselves with greater truth than a faceless public — with greater truth, even, than our own reflection. They alone keep our bodies in view. In turn, we must tell the truth about our neighbors. We are first of all responsible for keeping the body of our neighbors and only secondarily owed the same being-kept. It is not technology, but the ever-ancient and ever-new laws of charity and justice that will keep us from the suicidal effort of affirming our own face.