Several months ago, I came across what struck me as a particularly egregious proposal for university curricular revision—specifically, a push by Oxford University classics lecturers to remove Homer and Virgil from the first stage of the classics degree program. Proposals like Oxford’s were subsequently defended by Brandeis University classics scholar Joel Christensen, who penned an extended defense of relegating Homer to the “optional” category.

Several months ago, I came across what struck me as a particularly egregious proposal for university curricular revision—specifically, a push by Oxford University classics lecturers to remove Homer and Virgil from the first stage of the classics degree program. Proposals like Oxford’s were subsequently defended by Brandeis University classics scholar Joel Christensen, who penned an extended defense of relegating Homer to the “optional” category.

I’ve thought a lot about Christensen’s article in the months since I first read it, not just because I think most of his arguments are fundamentally wrongheaded—which I do—but because he’s right that if the only reason one can give for reading Homer is that “it’s part of the canon,” it doesn’t make a lot of sense to require it.

A history of uncritical reverence for a historic text, after all, doesn’t automatically mean that text is worth valuing. From that observation, Christensen makes the now-familiar case that texts are always essentially bases for the rearticulation of power—that in “function[ing] to advance a simplistic, but powerful policy of canon-enforcement,” they always necessarily impede students’ ability “to think critically, to re-frame the past, and then reclaim it.” Far better, for Christensen, to strive to “critically and pointedly examine the past,” which to his mind is the purpose of education qua education. On this view, the only reason we read the Iliad and the Odyssey as great literature is “because they have been selected and handed down as such.”

But surely this is a highly reductionistic account of education. How do the skills of “critically and pointedly examining the past” actually enrich one’s life? If education is to be more than simply the inculcation of dogma, some component of real personal formation must be involved. And anyone who says that good books don’t play a key role in that formation is, frankly, deluding himself.

More importantly, Christensen’s stance reflects an exceedingly narrow view of why certain stories survive while others are forgotten. For one thing, the general public doesn’t seem to agree with Christensen that these tales are nothing more than accidents of history, as attested by the success of Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles and Circe—novelistic retellings of the Iliad and the Odyssey through the eyes of Patroclus and Circe, respectively. Both have, perhaps surprisingly, turned out to be major bestsellers, and are testaments to the fact that that the classical stories of the West are not exclusively the province of “dead white males.” Miller’s books work because they preserve the emotional and moral questions of the source material while simultaneously pressing forward to consider—compellingly—the inner lives of Homer’s peripheral characters.

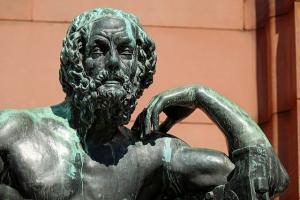

Nevertheless, Christensen complains that “[t]oo much of what we call ‘classical studies’ and canon are retrograde assumptions about the world and what it means to be human.” Maybe so—I’m not a classicist myself, and perhaps there are discipline-specific issues of which I’m unaware. But that doesn’t close the matter. The question of what it means to be human is itself universal, and it is precisely the point of reading Homer.

Yet to affirm that there is such a thing as a common human experience is to affirm that there are ways of being that are distinctive to human beings by nature, and not themselves subject to endless fragmentation and dissolution. In universal themes, as anthropologists like Rene Girard might say, lie universal truths. And so to have faith in the reality of a shared human experience is, in a very real sense, to have faith in an ordering of the cosmos that transcends the strictly subjective—an order that can be glimpsed in its various manifestations but never completely apprehended.

This order is what underpins the millennia-old resonance of Hector’s felt sense of duty, of Priam’s foreboding, of Odysseus’s primordial longing for hearth and family, and so on. And to be human—to experience those same sentiments—is to participate in that order.

Surely scholars like Christensen would refuse to concede that such an order exists, or that Homer can help shed light on it. Perhaps the claims I’m making about a common human experience are incoherent or reflect a desire to shore up my own social position. But, I daresay, most readers know better.