Last week, Samuel Moyn—a professor of law and history at my alma mater—published a provocative article in the Chronicle of Higher Education. Contra the widespread assumption that leading universities are incubators of progressive political ideas, Moyn argues that elite law schools are profoundly amoral, philosophically denuded environments.

To support his claim, Moyn points to schools’ reverence for judges qua judges, wholly irrespective of those judges’ actual decision-making histories; schools’ uneasy juxtaposition of activist “clinical education” training programs alongside institutional funneling of students into corporate law firm jobs; schools’ uncritical assumption that the “first principles” of the Anglo-American common law system reflect the best of all possible worlds; and so on.

If all this sounds arcane, I’ll put it more bluntly: while you’re a student, the school will give you a lot of money to sue big companies on behalf of the environment, while simultaneously encouraging you to take a professional job defending ExxonMobil against federal regulators as soon as you leave. And this dynamic does not tend to produce people willing to sacrifice themselves for their deepest convictions.

Moyn’s essay has already led to some thoughtful rejoinders from Yuval Levin and John McGinnis. They (incisively in my view) challenge Moyn’s thesis that the legal academy ought to double down hard on the left-wing ideology shared by many members of its faculty. Fair enough—there are good prima facie reasons to be skeptical of that ideology, and good reasons to support real intellectual diversity on university campuses.

And one might even suggest that Moyn’s argument, at least in the law school context, undercuts itself. After all, most law schools exist because everyday people need lawyers. They need people who will handle their divorces, prepare their wills, defend them against DUIs, prosecute assaults they’ve suffered, and so on. The world is not perishing for a lack of beard-stroking critical theorists with Ivy League law degrees. In suggesting that law schools ought to be more oriented toward social critique than toward, y’know, the actual practice of law, Moyn articulates a distinctly non-vocational way of thinking about the profession—and one that fails to shake the very assumptions of the “privileged elites” he critiques. If the top ten law schools fell off the planet tomorrow, whether or not they suffered from endemic hypocrisy, the American legal order would be just fine.

Nor is the tension Moyn identifies unique to law schools. For instance, in his recent book Talking Art: The Culture of Practice and the Practice of Culture in MFA Education, Northwestern University sociologist Gary Alan Fine examines the pedagogy of the contemporary art world and reaches conclusions that parallel Moyn’s. In Fine’s telling, today’s art schools and their faculties stress the necessity of disruption, discontinuity, and scathing political critique. Most of all, the art schools demand their students disavow the demands of the market (which prioritizes beauty, clarity, and other traditional properties of art). This forces students—many of whom are heavily indebted—to navigate between Scylla and Charybdis. Academic success, and the admiration of professional elites, demands that the artist double down on the nakedly ideological, the transgressive, and the distasteful; market success requires exactly the opposite.

That is to say, art schools have done exactly what Moyn urges law schools to do—but to what end? It’s hard to argue that this turn in art education has led to the production of truly influential political art. More likely, it’s simply alienated those who might otherwise be open to certain elements of social critique. Like McGinnis, I tend to think that Moyn’s vision of the law school risks producing a similar dynamic.

But it’s hard to deny that Moyn does have a point (for what it’s worth, I think he’s one of the most interesting, intellectually honest leftist thinkers writing today). Beyond the talk of judges and clinics and corporate law jobs, I think this is probably his real question: what is the real point of a comprehensive, liberal arts education?

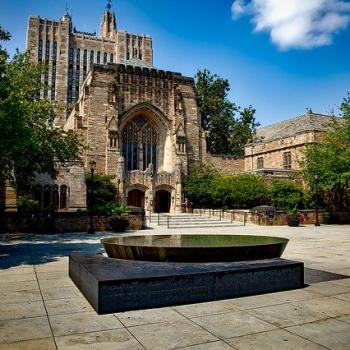

Yale Law School is not known for its focus on the nuts and bolts of “black-letter law” (nor, for that matter, are its immediate peers Stanford and Harvard). Academic courses generally prioritize thinking, in broad strokes, about the political, philosophical, and cultural aspects of the American (and global) social order. “Law” is simply the starting point for debates along these lines. And the school positively revels in the professional diversity of its alumni base—an extraordinarily large proportion of students end up in careers only peripherally related to actual legal practice. In short, the school’s juris doctor program is perhaps best described as a very pricey opportunity to spend three years thinking about the challenges of a cosmopolitan age. In many ways, it is a finishing school for the privileged.

But why have such a school in the first place? The question isn’t unique to Yale: despite the interdisciplinarity they extol, modern universities seem to have difficulty articulating why they exist at all. They clearly wish to offer more than straightforward vocational training, of the sort Moyn criticizes. They want to preserve the classical liberal arts.

Now, encounter with the liberal arts is fundamentally a catechetical experience—a process that, if successful, ought to shape our ideas, our desires, and our wills. And it ought to inform the moral views we hold: from a left-wing perspective, despite Marx’s pretenses toward a “science” of historical materialism, an ethical imperative of distributive justice cannot be deduced from scientific observation. Allegedly “neutral” universities, then, must wrestle with the notion that the liberal arts are irreducibly theological in character (in Paul Tillich’s sense of “theological” as “implicating matters of ultimate concern”). As James K.A. Smith once put it: “What if we began by appreciating how education not only gets into our head but also (and more fundamentally) grabs us by the gut? What if education was primarily concerned with shaping our hopes and passions—our visions of ‘the good life’—and not merely about the dissemination of data and information as inputs to our thinking?”

Thus, a university that truly cherishes the liberal arts must understand them as oriented toward a particular (teleological) end; else, they become deadweight to be shorn off by budget cuts.

This is a far more sobering thought, insofar as it seems to question the possibility of a “neutral position” from which liberal arts education can be conducted. It is to suggest that there is no privileged epistemic location—no perfectly rational, egalitarian, clear-minded pedestal, uninfluenced by upbringing and tradition—from which one can survey the most fundamental questions of life. And insofar as universities pretend to represent such a position, they are deluding themselves and betraying the liberal arts they claim to defend.

And so perhaps what Moyn is really saying is that educational institutions ought to more fully own their catechetical identities—that depending on their heritages, they ought to be more Catholic, or more Jewish, or (in the case of the left-leaning New School in New York) more committed to “challeng[ing] convention” and “nurture[ing] progressive minds.” And insofar as he understands Yale to be a fundamentally progressive institution, the law school is abdicating its mission by pretending to be neutral.

And that is a sharp, and ultimately accurate, critique.