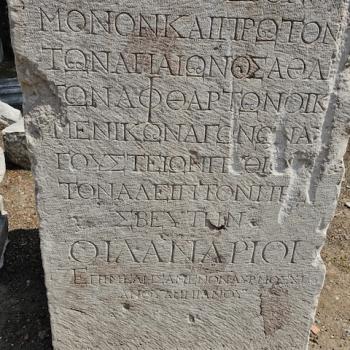

The word of the Bible was in many many ways a very different world than our world, and one of the major differences was the way ancient texts worked and how exactly they were read. A few basic facts first: 1) the literacy rate in the Greco-Roman world of the NT was anywhere from 10%-20% depending on where one was and what sub-culture we are talking about. When I say literacy, I am not referring to the ability to read the odd word or phrase, say of graffiti or a business sign. I can do that when I am in Turkey or Russia, but I am certainly not literate in those languages— I could not read whole paragraphs much less a whole manuscript. I am referring the sort of literacy that makes one a regular reader, and perhaps also a producer of ancient texts. And in regard to this, literacy was something mostly only elite persons had, persons with considerable education. When I say ‘elite’ persons, I do not necessarily mean wealthy persons, though most elite persons were wealthy. And unfortunately, when I say elite literate persons, the majority of these persons, and in some contexts the vast majority, were men, men like the chap you see to the left in this post, who could afford a marble sarcophagus with his face carved on it. 2) the second factor involved in this discussion is the nature of ancient texts, which were almost universally written in ‘scriptum continuum’, a continuous flow of letters. Even if one had some rudimentary Greek education and language ability, the very nature of ancient texts would be a real impediment to just anyone picking them up and reading them, if they had not been educated in them in the first place. Take a good look at the next picture in this post, a picture of a Biblical manuscript.

The word of the Bible was in many many ways a very different world than our world, and one of the major differences was the way ancient texts worked and how exactly they were read. A few basic facts first: 1) the literacy rate in the Greco-Roman world of the NT was anywhere from 10%-20% depending on where one was and what sub-culture we are talking about. When I say literacy, I am not referring to the ability to read the odd word or phrase, say of graffiti or a business sign. I can do that when I am in Turkey or Russia, but I am certainly not literate in those languages— I could not read whole paragraphs much less a whole manuscript. I am referring the sort of literacy that makes one a regular reader, and perhaps also a producer of ancient texts. And in regard to this, literacy was something mostly only elite persons had, persons with considerable education. When I say ‘elite’ persons, I do not necessarily mean wealthy persons, though most elite persons were wealthy. And unfortunately, when I say elite literate persons, the majority of these persons, and in some contexts the vast majority, were men, men like the chap you see to the left in this post, who could afford a marble sarcophagus with his face carved on it. 2) the second factor involved in this discussion is the nature of ancient texts, which were almost universally written in ‘scriptum continuum’, a continuous flow of letters. Even if one had some rudimentary Greek education and language ability, the very nature of ancient texts would be a real impediment to just anyone picking them up and reading them, if they had not been educated in them in the first place. Take a good look at the next picture in this post, a picture of a Biblical manuscript.

This one is different from some in that there are not two columns on each leaf of the papyrus but only one, one continuous flow of Greek letter. When you have a document like this, most ancients could not simply pick it up and read it. More elite persons could do so, but they didn’t have to, because most of them could afford ‘readers’— or as they are better called, ‘lectors’, people trained in the skill required to read such a document, and read it fluidly, fluently, without long pauses and stumbling and trying to figure out where

Reading in antiquity involved a different skill set than it does now in various ways, because these document had little or no punctuation, no chapters and verses, no separation of words—- you get the picture. Most ancient reading was done out loud, whether it was done by a lector, or you were reading to yourself. And it wasn’t just because of scriptum continuum that you did this. The other reason was, these texts were oral texts in the sense that they were meant to be heard, not silently read— they had oral and rhetorical devices in them which were best appreciated when read out loud, devices like assonance and alliteration, dramatic hyperobole, onomatopoeia and so on. Texts, even in the most literate parts of Roman society were read out lod and were composed aloud as well, by dictation. Indeed, as Raymond Starr has shown the verb ‘dictare’ which technically means to dictate, had come to also have the sense of ‘to compose a document’. (What follows in this post is indebted to Raymond Starr, “Lectores and Book Reading” Classical Journal Vol. 86 1990, pp. 337-43). Even business reading would normally be done out loud. Libraries and homes were noisy places when reading or composing was going on. And when we are talking about the reading of something even loosely poetic, it needed to be heard for sure—- take for example the Psalms. “The experience of the poem was also the experience of the reader’s voice” (p. 338). Starr goes on to stress “A reading that brought out the metrical effects of a poem or the rhythmical play of an oration or history would require a talented reader whose skills were kept sharp by regular, frequent practice” (p. 338). In other words, Theophilus would have needed a proper lector to really appreciate Luke-Acts. Don’t picture him poring over a manuscript by lamplight using a magnifying glass and silently reading while going to sleep at night. For that matter, don’t picture Paul’s letters being silently read either— they were basically orations sent within the framework of letters since they could not be orally delivered on the spot, and they were most definitely meant to be heard— full as they are of rhetorical and oral effects. And while we are at it—- Hebrews is a sermon, so is 1 John as well. They were definitely meant to be read aloud. Only strictly private correspondence like 2-3 John might be read by the recipient to himself, and yet those documents as well got into the canon. Who were these ‘lectors’?

Reading in antiquity involved a different skill set than it does now in various ways, because these document had little or no punctuation, no chapters and verses, no separation of words—- you get the picture. Most ancient reading was done out loud, whether it was done by a lector, or you were reading to yourself. And it wasn’t just because of scriptum continuum that you did this. The other reason was, these texts were oral texts in the sense that they were meant to be heard, not silently read— they had oral and rhetorical devices in them which were best appreciated when read out loud, devices like assonance and alliteration, dramatic hyperobole, onomatopoeia and so on. Texts, even in the most literate parts of Roman society were read out lod and were composed aloud as well, by dictation. Indeed, as Raymond Starr has shown the verb ‘dictare’ which technically means to dictate, had come to also have the sense of ‘to compose a document’. (What follows in this post is indebted to Raymond Starr, “Lectores and Book Reading” Classical Journal Vol. 86 1990, pp. 337-43). Even business reading would normally be done out loud. Libraries and homes were noisy places when reading or composing was going on. And when we are talking about the reading of something even loosely poetic, it needed to be heard for sure—- take for example the Psalms. “The experience of the poem was also the experience of the reader’s voice” (p. 338). Starr goes on to stress “A reading that brought out the metrical effects of a poem or the rhythmical play of an oration or history would require a talented reader whose skills were kept sharp by regular, frequent practice” (p. 338). In other words, Theophilus would have needed a proper lector to really appreciate Luke-Acts. Don’t picture him poring over a manuscript by lamplight using a magnifying glass and silently reading while going to sleep at night. For that matter, don’t picture Paul’s letters being silently read either— they were basically orations sent within the framework of letters since they could not be orally delivered on the spot, and they were most definitely meant to be heard— full as they are of rhetorical and oral effects. And while we are at it—- Hebrews is a sermon, so is 1 John as well. They were definitely meant to be read aloud. Only strictly private correspondence like 2-3 John might be read by the recipient to himself, and yet those documents as well got into the canon. Who were these ‘lectors’?

In Roman society at least they tended to be literate slaves, by which I mean, persons taken captive in the Roman conquests, who may well have been high status persons elsewhere or at least teachers or philosophers, who now, through enslavement, had become a Roman’s pet reader, educator, after dinner speaker etc. Not only did ‘lectores’ tend to be slaves or freedmen, so were most of the support staff as well– note-takers, clerks, copyists. These could all be different persons in a Roman household. But for the person who could only afford one literate slave or freedman he might well do all of these jobs. While most professional ‘readers’ were males there is a surprising number of inscriptions in the CIL mentioning female readers, three women ‘paidoagogoi’ are also mentioned and a number of women note takers and librariae (see n. 13 in Starr’s article). What we know is that buying a slave trained as a ‘lectores’ was expensive. They did not come cheap, and he would normally be expected to read both Latin and Greek texts at the drop of a hat.

But we must distinguish between ‘business reading’ and what we might call ‘pleasure reading’. A clerk would read back to his owner or employer a document. A secretary would read back normal secretarial correspondence. A notarius would take notes, but this seems to have been beneath the dignity and pay grade of a lectores. A lectores was expected only to read out loud (p. 340). Sometimes a lectores would read aloud his master’s works at a private recitation in a home or at a dinner party. The great man, say a lawyer, would of course give his own speeches in court, but home was the domain of the ‘lectores’ most of the time. And besides recitations for dinner guests, the lectores would do entertainment and pleasure reading for the family he served. Believe it or not, an oration or a reading was the main entertainment at dinner parties, with lyre playing, perhaps a short comedy skit, or dancing girls being on down the list. The elite wanted to appear to be literate, knowledgable, and they used their meals as occasions to ‘improve’ themselves, to become cultured. As Starr adds “lectores,,made it possible for their masters to listen to a work read at many times when that would have been awkward or impossible otherwise…Since one read a roll by rolling it from the right to the left hand, reading required two hands, but that inconvenience was completely circumvented by the use of a lector.” (p. 343). And of course the lector served as the eyes for a person whose eyesight had gone dim, but who wished to continue to learn.

It needs to be stressed that reading in antiquity was a considerable task. This is why Dio Chrysostom says “Have someone read to you, because you will get more out of it if you are spared the trouble of reading yourself” (18.6). If you had a lector, you could focus on the “literary work and not the work of reading” as Starr puts it at the end of his article. My blog readers may by now wonder, how exactly is this of relevance to our study of the New Testament? I am glad you asked. Let’s take a text like Rev. 1.1-4. The alert reader will notice that John distinguishes between the ‘reader’ of this text, and the hearers. The ‘reader’ in question is surely the person John sent to orally perform the Apocalypse, and indeed he would have had a huge task on his hands. Indeed, he was sent to seven churches to read this whopper of a document to each audience. And a good thing too, as they would hardly have been very able to decipher his rather Semitized and often inadequately grammatical Greek. It seems clear to me that such a reader would have had to be trained in the content of the document as well, to make explanations. It is probably that Paul used his co-workers, a Timothy or a Phoebe to orally deliver his discourses verbatim. And this brings us to why it was written down at all— when there were lots of things that the audience needed instruction on, and Paul did not want to just send a co-worker a long distance with vague instructions like— talk to them about the Lord’s Supper, he dictated these documents so his ‘lectores’ would only have to read it out, and then perhaps do some explaining. The verbatim was necessary as well to convey apostolic authority in what was said.

Take one other example— namely Mark 13.14 and its reference to a ‘reader’. This is a parenthetical note to the person reading out the document to Mark’s audience to be sure to explain about the sacrilege that is an abomination (an allusion to Daniel of course). It is not a note to us, who simply read the document for ourselves these days. It required a knowledgeable reader, a trained reader, who knew OT allusions and their references in such cases. And happily in Rome and other cities, early Christians had converted a few of these folks who served the Gospel simply by oral reading.