Steven Saylor, Empire. The Novel of Imperial Rome, (St. Martin’s Press, 2010), 589 pages $25.99 (hardback edition). There are a number of excellent novelist whose baileywick is the ancient Roman world, including Lindsey Davies and Colleen McCullough, but for my money none are better writers, or better informed about the period than Steven Saylor. It is a difficult thing to cover ground other writers have covered rather well, and bring something entirely fresh to the account, but Saylor manages to do this, perhaps especially so in his latest volume, which may one day be seen as his magnum opus. It is certainly the most ambitious of his novels thus far, and the grandest in its sweeping scope and attention to detail about the period between the time of Augustus all the way up to the time of Marcus Aurelius. And he confirmed to me recently he is likely to carry the story forward up through Constantine. As for this large tome, here is what Steven says about how long it took to write it—-

Steven Saylor, Empire. The Novel of Imperial Rome, (St. Martin’s Press, 2010), 589 pages $25.99 (hardback edition). There are a number of excellent novelist whose baileywick is the ancient Roman world, including Lindsey Davies and Colleen McCullough, but for my money none are better writers, or better informed about the period than Steven Saylor. It is a difficult thing to cover ground other writers have covered rather well, and bring something entirely fresh to the account, but Saylor manages to do this, perhaps especially so in his latest volume, which may one day be seen as his magnum opus. It is certainly the most ambitious of his novels thus far, and the grandest in its sweeping scope and attention to detail about the period between the time of Augustus all the way up to the time of Marcus Aurelius. And he confirmed to me recently he is likely to carry the story forward up through Constantine. As for this large tome, here is what Steven says about how long it took to write it—-

“It’s hard to give an exact time frame, since my research never stops and overlaps with my writing, but I would say I researched Empire for a couple of years and wrote it in 18 months, and then there was a year of production (doing the maps, reading the copy edited ms.).”

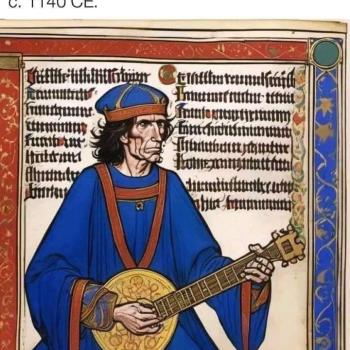

In character, this novel will remind some readers of the great classic novel by James Michener, entitled The Source in that it focuses on one spot (in this case Rome) and the story of one family over the whole period of time living in that spot (though the Source does skip generations as it works its way through the history of the tel— modeled on Megiddo). This however is not an archaeological epic in either the original sense of that word (words about beginnings of things) or its modern sense. Rather, it is the sequel to Roma which also was about the Pinarii. This novel is about the social history of the Pinarius family, patrician Romans and augurers by trade (for the most part) who are not in the corridors of power for the most part (none of the Pinarii are military generals for example, or notable or influential senators) but they have a remarkable run of being close to those in power (in part because they were related to the Julio-Claudian clan).

Thus we learn of the lives and loves and losses of the Pinarius family as the Empire rears its head on the Mediterranean landscape, and many of the stories told in this novel are both effective and affecting. The story of Lucius and Cornelia the Vestal Virgin is a story of forbidden love, full of pathos and power and some of Saylor’s best writing comes in this long central section of the novel. Along the way of course we learn a lot of history and a lot about day to day life in Rome. We fraternize with philosophers such as Seneca or Epictetus, or historians such as Suetonius or poets such as Martial, but we also run into holy men such as Apollonius of Tyana, a truly interesting person about whom it was claimed he could do miracles just like Jesus. Speaking of whom, we get a very clear picture in this novel about the marginal status and dangers of being a Christian say late in the reign of Nero, or during the time of Domitian, and Saylor does a very fair job of representing what Christian life must have been like in the subura in Rome. Kaeso Pinarius in fact becomes a Christian, and there is some mystery about this talisman he and others of the Pinarii wear— is it a fascinum (an ancient phallic symbol) or is it a golden cross of sorts. The issue is not resolved as this family heirloom is passed from one generation to the next.

The book is in fact divided up into four major (generational) sections– one on Lucius the Lightning Reader (A.D. 14-39), one on Titus and Kaeso the Twins ( A.D. 40-68), one on Lucius the Seeker (A.D. 69-112?), and one on Marcus the Sculptor (A.D. 113-141). By far the longest single section is part three which runs for almost 240 pages by itself, and worth every page of it too. At the very heart of this novel is ancient Roman beliefs about religion, immortality of the soul, astrology, augurer, and all things ‘superstition’ if one defines that term in the Christian sense. But of course as this novel points out, it was the Christians who were accused of atheism (a failure to believe in the traditional gods) and pernicious superstition in the ancient Roman world, not the pagans.

This is such a fine novel, and so carefully crafted that I hate to have to report that it is riddled with typos, words deleted and the like. I have had an exchange with Steven about this and he assures me that the forthcoming paperback edition will not have these errati in it, but for a careful reader who has already or wants to buy the hardback, this is one feature of the novel that will unfortunately be annoying, especially in the middle of the novel where it is noticeable on many many pages. As I told Steven, the day of good in house proof readers even at some major presses is long gone. We authors have to do our own dirty work these days.