Nomina Sacra in Early Graffiti (and a Mosaic)

(Larry Hurtado): In connection with my moving office I’ve run across a few journal articles accidentally misplaced, and have now taken the time to catch up in reading them. One of these is a stimulating study of nomina sacra (special abbreviated forms of certain key words in early Christian discourse) in graffiti, inscriptions and a mosaic, all of which are dated (with varying degrees of confidence) to the pre-Constantinian period:

James R. Wicker, “Pre-Constantinian Nomina Sacra in a Mosaic and Church Graffiti,” Southwestern Journal of Theology 52, no. 1 (2009): 52-72.

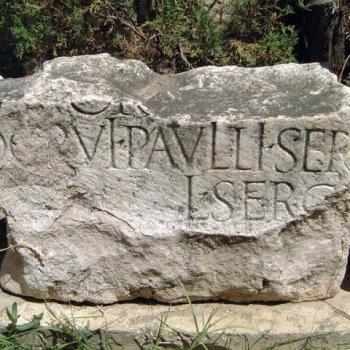

After briefly explaining “nomina sacra”, mosaics, and “house churches”, Wicker reviews evidence from “The House of St. Peter in Capernaum” (graffiti, some of which have been dated as early as the 3rd century CE, on plaster from a domus ecclesiae beneath remains of a 5th-century octagonal church), the “Prayer Hall” more recently unearthed at Megiddo (which includes a mosaic floor with a dedicatory inscription, dated by the lead archaeologist and an expert in epigraphy to the 3rd century), and the Christian structure found in Dura Europos in the early 20th century (confidently dated to the early 3rd century CE, featuring graffiti).

Starting from the most securely dated evidence, Dura Europos, we have gaffiti employing nomina sacra forms for the Greek word “Christos”. Likewise, in graffiti dated palaeographically to the 3rd century from the Capernaum site, we have graffiti using nomina sacra forms of the words “Kyrios“, “Iesous“, and “Christos“, “Soter“, and possibly “Theos“. Another curious feature of one graffito (#121) is what appears to be a monogram form of the Hebrew letters yod and he (Yah, a known abbreviated form of the Tetragram, YHWH), which appears twice along with the Greek letters “IHC T”, which may represent “Iesous” and the tau referring to Jesus’ cross.

I’m myself less confident about the “prayer hall” at Megiddo, as to the dating. On the one hand, I hesitate to take issue with Dr. Leah Di Segni (an expert epigrapher), who dates the dedicatory inscription to the 3rd century. On the other hand, it seems curious that there was a Christian meeting place that apparently formed part of a Roman military struture in the 3rd century.

In any case, from Dura Europos alone, it is clear that the use of nomina sacra forms extended well beyond circles of copyists of Christian manuscripts, and that a much wider body of people would have seen these visual expressions of Christian piety. Wicker is right to emphasize this. Moreover, the Dura Europos evidence is almost as early as our earliest manuscript evidence, and confirms also that the nomina sacra practice was observed trans-locally from a very early point, e.g., evidence from Syria as well as Egypt. If we throw in the Capernaum evidence (Galilee), this is further confirmed.

To my mind, this also further confirms the view that nomina sacra served primarily as expressions of Christian piety, and not simply as short-hand devices.