Hermeneutics of ‘Agape’

by larryhurtado

In my inaugural lecture as Professor of New Testament Language, Literature & Theology (1996), “New Testament Studies at the Turn of the Millennium: Questions for the Discipline,” I devoted a section to “The ‘Postmodern’ Challenge to New Testament Studies” as to the interpretative task. (The lecture was later published in Scottish Journal of Theology 52 [1999]: 158-78.)

I acknowledged gratefully “the critique of naive epistemological assumptions and the hubristic claims of some historical critics of past and present,” and also that “the efforts of every interpreter are affected by his or her historicity, in time, geographical and cultural setting, language, life-experiences, gender, values, biases, beliefs, vices and virtues.” But I also then explored (in a very preliminary way) what sort of hermeneutic might arise from and reflect NT and Christian emphases. I advocated there what I called “a hermeneutics of agape” (p. 174-77).

As I indicated in a footnote, to my knowledge, this was my own phrasing, though influenced by various things I’d read. Subsequently, I’ve noticed a few others who have used very similar expressions. In particular the following: Alan Jacobs, A Theology of Reading: The Hermeneutics of Love (Boulder, CO/Oxford: Westview Press, 2001); and also Tom Wright’s brief discussion of what he called “a hermeneutic of love” in The New Testament and the People of God (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1992). I now think it’s possible that Wright’s comments lodged somewhere in my mind and helped to prompt my own particular phrasing.

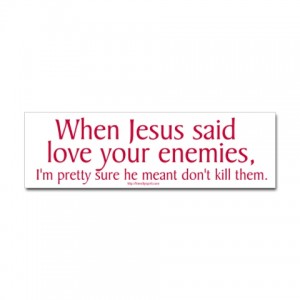

In my own brief exploration of the idea, however, I may have teased out (if all too briefly) a few distinctive suggestions. I emphasized, for example, it is agape, with all the rich and powerful connotations attached to term that derive from the many NT statements in which it is used. Agape in the NT dominantly is used in statements about God’s redemptive efforts, and about believers’ responsibility to care for others in various relationships, even one’s enemies. This is why I probably chose to retain (and then explain) the word “agape” rather than “love”, given the heavily romanticized drift of the latter word in modern usage.

So, agape isn’t the same as eros, the latter typically implying some sort of delight or pleasure taken in/from the object of one’s “love”. One can (indeed, believers must) exercise agape even toward people, and texts as well, that we may regard as “incorrect, disagreeable and even repellent”. (As someone once offered encouragement about parenting: “You don’t always have to like your kids; you just have to love them.”)

A hermeneutics of agape is “a critical reading of a text, but also carried out in recognition that our own critical faculties and moral or aesthetic judgements can be refined and enhanced, perhaps even challenged, by authentic engagement with the judgements of others that may be reflected in the text and in the larger interpretative community” (p. 176).

To give a rather extreme example, a hermeneutics of agape could be applied even to a work such as Mein Kampf, and “would have very critical things to say” about its contents. “But even radical critique is fully within the scope of agape guided by seeking to serve truth and promote human flourishing” (n. 18).

The jist of my paper is that (1) the NT emphasis on the biblical deity as loving the world, and this love as the prime basis for God’s acts toward the world, are rather novel in the Roman religious environment, and (2) that this divine love serves rather consistently as the basis and pattern for the actions that believers are called to exhibit.

I make no claims about how consistently Christians have actually lived up to this. Heaven knows it’s hardly a consistent record! Perhaps all the more reason to return to the NT texts every so often.

I can’t close this posting without including my reference in my lecture to one of my favorite sayings by Blaise Pascal: “Truth is so obscured nowadays, and lies so well established, that unless we love the truth, we shall never recognise it” (trans. A. J. Krailsheimer, Pascal Pensees [Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966] 256 (saying #739).