What is the nature of human nature? What are we intended to be…. and to do? The Feast of the Incarnation, when the Son of God took on human flesh is the perfect time for a meditation on this very subject. Professor K. Scott was giving a chapel address at Asbury last month, and he was stressing that God created our world in such a fashion that we might grow up and grow into our true humanity, like Jesus himself who, according to Lk. 2.52 ‘grew in wisdom and in stature and in favor with God and human beings’. Scott went on to say that all too often when we compare ourselves to Jesus we immediately become frustrated and despair precisely because the disparity between God and humankind is so great. How could we imitate God, after all.

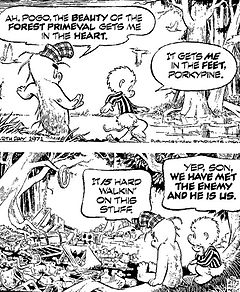

Think for a moment of a stereotype contrast between your own day and a day in the life of Jesus. Jesus rises early and prays for four hours. I get up, wash my face and make the coffee. Jesus heals two people before breakfast, I put on my robe and read the morning paper online. You get the sense of it, and it leaves the average Christian thinking that such comparisons are inherently self-defeating. If Jesus is the model of true humanity, then I shall never be truly human. End of story. We are our own worse enemies (see the Pogo cartoon above). We are weak and vulnerable and constantly fail at things. Why not just one more failure at being truly human? Comparing us to Jesus just ratchets up the sense of inevitable failure.

As it turns out however, this is not quite the way to think about this topic. First we must ask ourselves how we were created, and the answer is we were created to be neither gods (sorry Mormons) nor dogs. We were created to be something in between. Neither the masters of our own fate nor the dogs who cringe at their master’s feet waiting to be led around on a leash. Now of course either of these images of ‘true humanity’ will have a certain appeal. If we are like gods, then we ‘can climb any mountain, ford any stream, follow any rainbow until we find our dream’. If we are inherently godlike then we can save ourselves, and what need would we have of the Incarnation, unless it be just an illustration of our own innate potential. The Bible of course flatly denies that this is the nature of true humanity. Indeed God himself is constantly saying things like ‘I am God and not a human being’ (Hos. 11.9). We need to listen to that credo. The key here is that we are called to be both truly human and Christ-like without developing a messiah or god complex. For as it turns out, we are called to emulate Christ’s true humanity, not his divinity.

Oddly enough in this world of high danger and terrorism and high uncertainty about what the future holds, there are all too many Christians who are prepared to trade in the heady prospect of being truly human for accepting that we are simply dogs on God’s leash. We need not make plans, we need not grow up, we simply need to allow ourselves to be led around by our higher power, our master. We are simply called to be perpetual infants in Christ, who need not worry about discerning or carrying out or growing into God’s will because, after all, God is in complete control from before the foundations of the universe and my will really has nothing to do with it. Of course this is a bit of a rhetorical exaggeration to make a point, but to the degree that it is true, to that same degree it prevents us from seeing what God intended for us to be, prevents us from being all we can be as truly human and never gods.

Interestingly enough, it is precisely when we abandon the high calling to be truly human and emulate Christ that we descend to being like lesser creatures like dogs barking at one another, viciously defending our own turf, attacking others who invade our space, devouring other people resources, urinating on other country’s lawns, and so on. It is not an accident that Daniel, when he envisions world empires other than the empire of the Son, the kingdom of God, calls them beastly, sub-human, self-centered, brutal, vicious, led by beasts with powerful and ugly horns on their heads. This also is not a vision of true humanity at all. It is ‘the one like a Son of Man’ who comes down from above and gives us a glimpse, however fleeting, of true humanity. So what does that look like?

First of all, we need to understand, that Incarnation means the Son of God deliberately took on human limitations of time, space, knowledge, power, and mortality in order to be truly and fully human. He did not renounce his divinity, but he did refuse to draw on his divine prerogatives— the omnis, as they are called— omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent etc. No, Incarnation means that while Jesus had access to the omnis, his great temptation as Lk. 4/Mt. 4 show was to push the God button and obliterate his true humanity, obliterate the limitations he assumed since conception. Notice that in the temptation in the wilderness Jesus does not say ‘I’m God, God can’t be tempted, ergo…. be gone Satan’. No, Jesus had real temptations to act in ways only the divine Son of God could act, and he resisted them. I’ve known a lot of persons who could turn bread into stones (ever been to a church potluck dinner?) but I’ve never met a sane person who was tempted to turn stones into bread and believed it was possible. Jesus resisted the Devil in the desert by using only the two resources we have to use— the Word of God and the Spirit of God. Jesus lived his whole human life drawing on those resources, the same two resources we as Christians have to use to live a godly life. Now we begin to get a glimpse of true humanity. Humans have God and his Word as a guide and an aid empowering and enlightening us, but God is not going to make all our decisions or live our lives for us. We must grow up. We must make free choices, and most of all we must relate to the God of love with love– freely, openly, and without pre-determination. True love, like true freedom, requires space, and a lack of predetermination. Otherwise, at the end of the day the inevitability of things is running the show, and we shall never be free, never truly love, never emulate Christ.

Here is a question you may have never considered? Did God pre-destine every move that Jesus made before he ever sent his Son to walk the earth? Did Jesus, as truly human and also truly divine, have the power of contrary choice? Could he have possibly sinned? That depends on how you envision the nature of God’s sovereignty and how it works, and how you envision the nature of true humanity and how that’s supposed to work. It depends on the depths of self-abnegation the Son underwent to become truly human, doesn’t it? If, as Paul suggests, Jesus was like Adam, only gone right, tempted like all of us in every respect, save without giving in to sin, what does that tell us? Did either the first or the last Adam have true freedom, the power of contrary choice, or were they led around on a leash called pre-determination? It is my view that God is love, as 1 John says, and that he has made us all with the capacity to truly love— freely, fully, and without predetermination. Indeed, were there predetermination, there could be no love as defined in the Bible itself. Being created in the image of God and renewed in the image of Christ means that God has gambled on our growing up and growing into true humanity where we become what we admire, we become Christ-like without becoming gods.

Becoming truly human requires space, time, a modicum of free choice so true love becomes possible. It means God has to allow us to fail, just as parents must do with their children if they ever hope for them to grow up, cut the apron strings, and become mature adults. The relationship of God with his human creatures has that same tension, that same delicate dance as the relationship between parents and their grown children. You can advise, but they must consent. You can urge, but they must feel the urge. You can cast a vision, but they must catch the vision. And if you cross the line and violate their growing maturity, violate their will, and they become co-dependent or decide they do not have to grow up, then you have stripped them of their potential of becoming truly human, all they are meant to be. Of course, there are extreme circumstances where that line has to be crossed as a lesser of two evils. When you have an adult child that is a cocaine addict, there has to be tough love, and sometimes even a violation of their immediate wills or urges. Of course that is true. But that is no model of how it ought to be, or how God always intended it, or how love should normally work. No indeed.

To be truly human means to understand we shall never be gods in our lives, nor should we degenerate into mere animals led around by our urges, needs, beastly instincts. It means to be something in between these extremes. It means to be like a Jesus who accepted all the natural limitations of being human without ever excepting the inevitability of sin. It means being like a Jesus who lived his life in constant communion with his Father, and by the Word of God, led by the Spirit of God. It means he, and we, never outgrow our need for God and his Word and his Spirit, but at the same time, we are on a journey towards Christ likeness, towards being Jesus friends, being his brothers and sisters, not merely his slaves. And this means we must grow into the way of making Christian adult choices. There are moments in Paul’s letters where he treats us that way, and says things like ‘let each be persuaded in their own minds’ (about the day of worship issue, for example). He says things like ‘evaluate your maturity level, and whatever you cannot do in good faith, is sin for you, even if it is not sin for a strong mature Christian’. Jesus and Paul call us to pursue true humanity, true maturity in Christ, and not view that as an impossible dream or an exercise in pure futility.

As it turns out, full conformity to the image of Christ does not mean we become gods. It means we partake of the true human nature of Christ in the spirit, but also by resurrection in the flesh when he returns. What does it mean to grow up in Christ, and to emulate his true humanity? Read again the Gospels including the birth narratives asking that question. Read again about a Mary who willingly and freely said to the angel ‘be it unto me as you have said, I am the handmaiden of the Lord’ and a Jesus who said ‘did you not know I had to be about my Father’s business?’ which is rapidly followed by the commendation that this very statement, and yet the paradoxical free choice to go home with and honor his parents showed that he was continuing to grow in wisdom and in stature and in favor with God and human beings. Figure out what that looks like for yourself, and then set yourself on a course to live into it. During this Christmas season perhaps instead of being like babes in toyland we might contemplate finally growing up in Christ. It is a consummation devoutly to be wished.