As Tom admits, in discussing the phrase ‘The Redeemer/Deliverer’ (p.1251) in Rom. 11.26-27, Paul does elsewhere use the cognate phrase, ho rheumenos’ very clearly to refer to Christ’s return and delivering his people from wrath in 1 Thess. 1.10. And I would say there is no reason it can’t mean that here in Romans as well. Tom seizes on the Isaianic phrase “whenever I take away there sins” and while he is right that this could refer to multiple actions rather than one single action in the future, there is nothing in the phrase itself that favors the former rather than the latter. It can mean either.

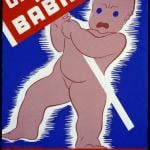

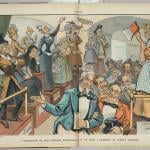

In the discussion on p. 1252, Tom places a good deal of weight on a textual variant. In 11.31 should the second ‘nun’ (now) be considered part of the original text. With its inclusion the text reads “…so that they may NOW receive mercy”. In other words, now as opposed to later, and so this is not a reference to some parousia blessing. This reading of course provides fodder for Tom’s argument that Paul is not talking about some mercy God will not have on Israel until the eschaton, but rather ongoing mercy on those repent and believe in the Gospel. Here however is what Metzger’s Textual Commentary (2nd edition), p. 465 says: “A preponderance of early and diverse witnesses favors the shorter reading”. Yes indeed. The external evidence certainly favors the omission of the second ‘nun’. P46, one of our earliest witnesses, does not have this 2nd ‘now’. Furthermore, there were scribes who could make no sense of the term here, and changed it to ‘later’ because they understood the text to be referring to a still future event. The textual committee and Nestle/Aland place the word in square brackets to indicate real uncertainty about it being the original reading. Is it the more difficult reading? Certainly not the further and further one gets in church history and the less and less emphasis is placed on the parousia and eschaton. It makes perfect sense that after Constantine, and even before Constantine, various scribes might add this word, because of the ongoing efforts to either convert Jews, or eventually to ghettoize them. The increasingly anti-Semitic portions of the overwhelmingly Gentile church did not want to hear that God still have plans of mercy for Jews in the future. They wanted to hear that the church had simply displaced Israel. Instead of mercy on Jews we have the growing libel that Jews should simply be seen as Christ-killers or obdurate blind people who would never accept the Gospel (see for example the statue on Strasbourg Cathedral below– here we have an image, said to represent the synagogue, which depicts a woman who has a veil or blindfold over here eyes. She holds a broken spear in one hand and a book she cannot read in the other).

The addition of the second ‘now’ suits the notion that Paul is just referring to his own day, when Jews were coming to Christ, though not in great numbers. While it is possible that the second ‘nun’ is original, the balance of the evidence is against it.

p. 1255 brings us to the climactic point that God has shut up all in disobedience, so that he might have mercy on all, and here all includes both Jew and Gentile. I agree with Tom that Paul’s view is that Jews must repent and receive their savior, whether now or later, in order to be saved. He thinks that the hardening of those who have rejected Christ now is temporary, during the time when God is having mercy on Gentiles and bringing their full number in. This is why he said they could be grafted back in, so Gentiles have no reason to think they have displaced Jews in God’s people. Of course Tom is right that the Good News for the Jew continues to beckon down through the ages, and is never foreclosed, but the reality of church history has proved Paul exactly right. Only some, a minority of Jews, sometimes a tiny minority, have accepted Christian down through the ages. Paul says this is not unexpected in view of both the hardening of them and the time of the Gentiles streaming into the people of God. All along, God had a plan that answered the anguish expressed in Rom. 9, but Paul skillfully does not reveal all until the very end of this argument.

As Tom says on p. 1256, the argument moves from lament in 9.1-5 to praise in 11.33-36. And strangely, while Tom has suggested that 11.31— is not about Jesus (the Deliverer will come from Zion), he now thinks that despite no clear reference to Jesus 11.33-36 is about Jesus. Now, I agree with him that for Paul Jesus is God the Son, and so inevitably what is all about God is also all about Jesus especially if we are talking redemption. I would simply say Jesus is indeed referred to in 11.31, as well as alluded to in the final benediction in this section.

On p. 1258, Tom tells us his sketch of Pauline theology— monotheism, election, eschatology being the big ticket categories which he used to arrange the discussion. Of course, this book goes on for another 257 or so pages! But the main discussion is now done, and stands or falls on its own merits. I agree with Tom when he says on this page, that the minimalist approach, sticking to only what Paul says, and never trying to figure out the gaps and follow up the hints, is in the end not adequate. Paul implies as much as he clearly states, and so the question is whether we will follow the bread crumbs into the center of the maze, and then out again. Tom is to be highly commended for making a gigantic effort to understand the full scope of Paul’s thought world and present it in all its richness, diversity, but also coherency. No one, to my knowledge, has spent 10 years doing such a labor of love in recent scholarship, and he is to be commended at length. It is the mark of any good and important work that it causes one to pause and rethink one’s own views, and either confirm them, or change them. This book is a huge catalyst and allows to do that at length, without rushing, without cutting corners, without neglecting something important. The fact that I have often disagreed, as well as often agreed, with Tom’s reconstruction does not in any way change the importance and usefulness of this book. It has certainly helped me to clarify my own thought. It is a book to be chewed over carefully, not swallowed whole.

On p. 1260, Tom once more suggests that in a sense Paul was the first theologian, or at least the first Christian theologian, and that since he was helping create a community which did not continue the usual boundary markers of Judaism (circumcision, food laws, sabbath, ethnic identity) the glue that he provided to hold the community together was not so much praxis as theology, a Christological and pneumatological re-envisioning of the themes of monotheism, election, and eschatology. “In Paul’s hands, ‘theology’ was born as a new discipline to meet a new challenge…. Theology is what Paul used to bring depth and stability to the worldview of his churches.” (p. 1261). But as Tom adds, “He does not supply all the answers, even to the comparatively few questions he addresses. What he does is teach his hearers to think theologically: to think forward from the great narrative of Israel’s scriptures in to the world which the Messiah had established God’s sovereign rule among the nations through his death and resurrection, inaugurating ‘the age to come’ rescuing Jews and gentiles alike from ‘the present evil age’ and establishing them as a single family…” (p. 1260).

On p. 1261 Tom says that he has laid to rest the libel of F.C. Baur that Paul abandoned his Jewish framework of thought to establish a new religion. No, days Tom, he was all about producing a new sort of fulfilled Judaism. On p. 1262 Tom raises a question that he intends to deal with more fully later in the book— namely, what kind of Jew was Paul? Tom suggests “He was a Messiah man; but nothing in Judaism had prepared him for what a Messiah man might look like if the Messiah has been crucified. Paul had to work that out from scratch, and some of his sharpest theological expressions occur when we can see him doing exactly that” [e.g. in Gal. 2.15-21].

Tom adds on p. 1263 that Paul does not really much look like the later rabbis, particularly in the way he handles Scripture. “The role which the rabbi assigned to Torah– the mode of YHWH’s presence, the guide of his people– was for Paul, taken rather obviously by Jesus and the Spirit. Torah does indeed continue to play a role… But Israel’s Torah is now playing at best a second fiddle to the new revelation which has taken place.” I find this comment mildly ironic in a book that has tried to show how thoroughly Jewish and thoroughly saturated in the OT Paul’s thought is. And in addition to this, when Tom addresses the possibility of ‘new revelation’ a mystery revealed to Paul and hitherto unknown, which Paul shares with his audience, such as the future of Israel, Tom wants to back away from the burning bush and say…. well know, the mystery is really just a further exposition of insights into the OT text. Which is it? Yet he adds “Paul then is a Jewish thinker for the gentile mission; a covenant thinker who drew together Israel’s sense of historical tradition and the apocalyptist’s dream of a totally fresh revelation.”

What was Paul’s stance vis a vis ongoing Judaism. Tom says this on p. 1264, to the dismay of more than a few…..

“As to his native Judaism, his critique was not that it was bad, shabby, second-rate, semi-Pelagian ot concerned with physical rather than spiritual realities. His critique was eschatological: Israel’s God had kept his promises but Israel refused to believe it. The Messiah had come to his own and his own had not received him.” He then draws an analogy between the Christian community and the Qumran community saying “the [Qumran] community believed that God had secretly re-established his covenant with them, leaving Israel behind the game, so with Paul. He believed the sun had risen, while most of his fellow Jews were insisting on keeping the bedroom curtains tight shut.” To this one must say yes… and no, not least if one believes, contra Tom, that one day Israel will indeed make an about turn in the right direction. It would irony indeed if a movie was made based on Tom’s theology called ‘the left behind people’ and those turned out to be Israel! What would those in Dallas say???