In the Introduction to Craig Blomberg’s new book on the trustworthiness of Scripture, he lays down some premises which let us know his orientation from the outset. Inerrancy will be a big topic in this book so he lets us know from the outset that “not a single supposed contradiction [in the Bible] has gone without someone proposing a reasonably plausible solution.” (p. 2). On the questions Doesn’t the Bible promote slavery, Blomberg’s brief answer is no but God allowed it, and “in Israel it was primarily an institution for enabling individuals to work themselves out of debt and return to free status. In the New Testament even more countercultural teaching appears, with numerous seeds that would eventually germinate into its abolition altogether— abolition that was disproportionately spearheaded by Christians.” (p. 2). He then treats briefly the idea of genocide in the OT. Perhaps the most important thing he says on all such subjects (which he only treats briefly) is this—“But for the Christian, it is also always important to stress that central to Jesus’ ministry was the abolition of some of the potentially most offensive practices in ancient Israel. It seems impossible to avoid the conclusion that God has worked with humanity gradually over time, progressively revealing more and more of himself and his will as humans have been able to receive it, which also suggests that there are trajectories of moral enlightenment established on the pages of Scripture that we should continue to push even further today.” (p. 4, emphasis added). I agree with this commitment to the notion of progressive revelation, but many conservative Christians would not necessarily do so, as they do not accept the idea of progressive revelation, especially if it is used to justify going beyond, and eventually against some specific teaching in the Bible. Craig is not endorsing the latter, but it is well to mention that the concept of progressive revelation has been used to ‘progress’ beyond the Bible in various matters— for instance in the recent debates about homosexuality.

A second major principle of Craig’s is (p. 5) that we must enter into the worlds and contexts of the Biblical writers in order to understand the meaning of these texts. We must engage empathetically with the worldviews of the writers as well.

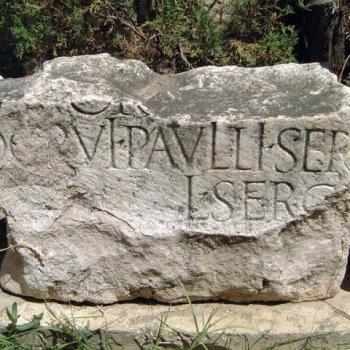

One of the things that prompted this book is that recent discoveries have actually strengthened the case for the reliability of Scriptures (though this book does not much refer to archaeological discoveries). (p. 7). I wish he had said more about this, but there is some new light in the discussion about textual criticism and the like. I agree with him that we are in a better position than ever to reconstruct the earliest form of the Biblical text, in a far better place than in previous centuries. Blomberg is also right that we know far more about the non-canonical literature from ancient Christianity than ever and about the reasons for not taking them on a par with the New Testament (p. 9). In the next post we will interact with what Craig says about textual criticism.