Here is the original form of the article I wrote for CT which appeared in their March 18th issue…….

AND DEATH SHALL HAVE NO DOMINION— Mark 5.21-43

Ben Witherington, III

There are all sorts of miracle stories in the Gospel of Mark—exorcisms (which are common in Mark and completely absent in John), nature miracles such as the feeding of the 5,000, healings of various sorts, and of course raising the dead. In Mark 5.21-43 we are presented with Jesus as both the healer and the raiser of the dead. Both of these miracles are meant to help persons return to normal life and are not used by Jesus to ‘prove’ who he is. We will say more about that shortly.

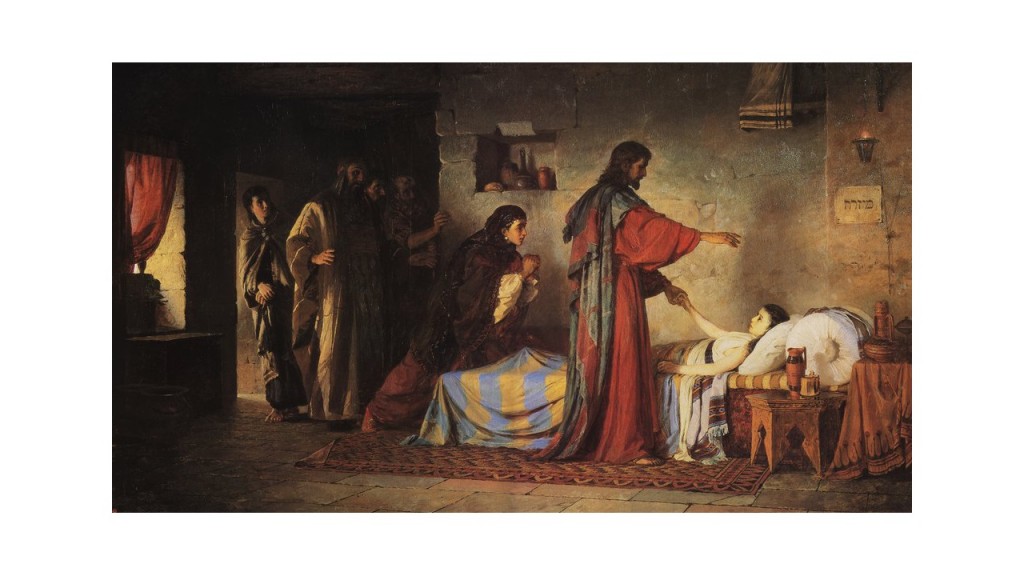

The story of Jairus and the Jewess in Mark 5.21-43 is a classical example of Mark’s use of the ‘sandwich’ technique of editing, in which he begins one story, inserts a second tale into the middle of telling the first story, and then finishes the first story. Part of the point of this rhetorical technique is to get the listener to consider the relationship between the two stories and what their similarities and differences are. In fact, both stories in this segment of Mark 5 are about women in distress, one an older woman who has had an issue of blood for twelve years, and the other a tale about a girl who had only lived as long as the older woman had been continually bleeding. The older woman had suffered greatly, and presumably had been seen as unclean by those who knew about her malady, whereas the young girl dies during the course of this narrative. The issue of ritual uncleanness is not foregrounded in this passage but it is latent. A woman was considering ritually unclean during her menstrual period, and if one had a continual flow of such blood, one was considered continually unclean. Corpse uncleanness is the sort of ritual impurity Jairus’ daughter would have confronted Jesus with, but Jesus has no concerns about ‘contamination’ in either case. His healing power not only negates but overcomes not merely ritual impurity but the very causes of ritual impurity. Not even death can stop him. In both cases, it is Jesus the healer to the rescue, but in different ways.

The emotional gestalt of both stories is desperation, desperation in an age where medicine was a primitive art, and often ineffective. People died of things we can’t imagine them dying of in the twenty first century. But transcending the fear and peril and desperation there is also the theme of faith and miraculous healing. One of the things that is most interesting about Jesus is that his miracles are always intermittent acts of compassion.

Jesus doesn’t put those mighty acts on his day to day ‘to-do’ list, he is just responding to the needs presented to him as he went around preaching and teaching. Mk. 1.38 tells us, from near the beginning of that Gospel, that Jesus saw his mission as preaching and teaching. This is why he went from place to place, sharing the Good News. But when he was confronted with a physical need, he stopped to heal. What makes the story in Mark 5 so intriguing is that Jesus, on the way to heal one woman, is delayed when he is confronted with the need to help another. It is one miracle tale inside of another, neither of which were part of the original plan for the day, apparently. And ironically, the first miracle which causes the delay, makes the second one appear to come too late.

The relationship between faith and healing is a complex one in the Gospels. Sometimes Jesus heals in response to the faith of a needy person, sometimes he heals before they have faith, sometimes he responds to the faith of others who bring the ill or injured person to Jesus, and sometimes he simply heals with no faith to speak of mentioned in the story. Faith is not a pre-requisite for healing, but there is obviously a positive correlation between faith and healing by which I mean that faith seems to make a person more ready or receptive to the possibility of healing. The opposite of this can be seen in Mk. 6.5-6 where the lack of faith, or better said the willful disbelief was an impediment to Jesus doing healing in his home town.

Notice that in fact Jesus is not satisfied with just any kind of faith. The woman who thinks she can be healed by touching the garment of the magic man needs her faith elevated to a personal level— so Jesus tells her that it was not the touching of the robe of a holy man that healed her, but rather her faith in Jesus’ ability to heal which has rescued her. In this story ‘saved’ means ‘healed’, it does not have its later Christian spiritual connotations. Vs. 30 is one of the most intriguing verses in all the Gospels. It suggests Jesus is a repository of healing power, it is virtually oozing out of him in response to those who reach out to him with even a modicum of belief or faith. Many in the crowd brushed up against Jesus, but only one reached out in faith. Unfortunately we see all too many examples of inadequate types of faith today— for example ‘word of faith’ or ‘name it and claim it’ notions that suggest that if one simply believes sincerely or powerfully enough one can ask anything of God and he is forced to dispense it.

Unfortunately for this approach it is sub-Biblical, and it is simply not true. If we ask for God to give us something that is against his will for our lives, or worse against God’s warnings about things like greed, wealth and the like in the Bible, we cannot “make God an offer he can’t refuse”. God is not a cosmic waiter or genie chanting “your wish is my command”.

But what of the story of Jairus’ daughter, the one Jesus had originally set out to help while she was ill? Tragically, she died during the delay in Jesus’ reaching Jairus’ house. One can only imagine how despondent Jairus and his wife must have become at that moment— there was a remedy in the vicinity, and yet, it seemed it arrived too late. As I said, one of the themes binding the two healing stories together is faith. And so when the tragic news comes to Jairus telling him to not bother Jesus any more since the girl has just died, Jesus says to Jairus “don’t be afraid; just believe” (vs. 36).

Notice that Jesus does not allow anyone into the room where Jairus’ daughter lies dead, except Peter, James and John, and the girl’s parents. Jesus doesn’t use miracles to prove who he is, they are simply acts of compassion. He’s not interested in wowing people into the Kingdom, and in fact you can’t impress people into the Kingdom. Amazement is not the same as faith. There are plenty of places in the Gospels where we are told that the crowds were amazed, but this is distinguished from those who believe. Believing leads to seeing, but the reverse is often not the case.

As for texts like Mk. 2.10-11, they do not demonstrate that Jesus uses miracles to coerce people into faith. In fact, what he says there is that ‘in order that you might believe the Son of Man has the power to forgive sins’ I will help this man regain the ability to walk. In other words, the miracle is subsumed under the heading of the more important matter—believing Jesus can forgive sins. It is not the physical miracle that ‘proves’ who Jesus is. After all, both older prophets like Elijah and later disciples like Peter performed miracles and this did not prove they were the Messiah. No, it is the message of the Good News about repentance, forgiveness, and everlasting life that Jesus says is the focus of his mission.

Notice as well that Jesus refers to the state of the little girl as ‘sleeping’. This was a term used as a euphemism for death by early Jews who believed in resurrection. Death was no more permanent than sleep if you believed in resurrection. It was something you came back from refreshed and renewed. It is not a belief that the dead are snoozing in the afterlife. Notice as well in vs. 39 the laughter when Jesus says the girl is ‘asleep’. This is probably the reaction not of cynical family members but of the hired mourners who were paid a fee to come and mourn the dead and play sad music at the locale where it happened.

The story ends of course with Jesus speaking to the corpse in Aramaic, saying ‘little girl arise’ and then immediately, or as the KJV used to say ‘strait way’ she stood up, began to walk around, and Jesus instructed those present to give her some food, but also gave strict orders to tell no one about what happened. Jesus was not concerned about getting the credit or a reputation of being a wonder worker, he was only concerned about the little girl getting the cure, and he wanted her, as much as possible to go back to her normal life without becoming an object of gossip and gawking.

It has often been noted that one of the major themes of our earliest Gospel, Mark’s Gospel, is the Messianic secret motif. Jesus silences demons and human beings, including even disciples when they speak publicly about who Jesus is. In some cases this seems to be because Jesus wants to define himself on his own terms, and the terms other people are using may be true but are inadequate. Sometimes Jesus doesn’t want a credit reference from a demon! Sometimes it is a matter of timing— Jesus will reveal his identity in his own good time. I suspect the main reason Jesus used the Son of Man language to speak of himself is because it was not the common language used in messianic speculations of that era. Jesus would carve out his own niche and not try to fit into people’s preconceived notions about the Messiah.

This story took on new flesh for me in a dramatic way, when four years ago our thirty two year old precious daughter Christy was suddenly found dead in her apartment only a few days after she had been here in Lexington celebrating my 60th birthday. She was felled by a pulmonary embolism, which no one knew she was in any danger of having. Suddenly, I had that same sinking feeling that Jairus and his wife must have had when I got that shocking midnight call from Durham N.C. that Christy had gone to be with the Lord. Having a child die prematurely is every caring parent’s perpetual nightmare. Part of my grieving and self-therapy was to tell this in a little ebook for CT called ‘When a Daughter Dies’.

But it was not just that I suddenly identified with Jairus. It was that Jesus’ Aramaic words suddenly had a galvanizing effect on me. When people ask me if I am looking forward to going to heaven and being with Christy and my other loved ones when I die, I reply that while that would be great and may well happen (though the Bible says nothing about physical family reunions in heaven), what I’m really looking forward to is when Jesus comes back and raises the dead.

I’m hoping on that Easter sequel day to hear him say these very words once more— ‘Talitha koumi’ to my Christy, so I can once more embrace her and kiss her, and tell her I love her in a direct and tactile encounter. I think there is a good reason why 85% of the discussion of the afterlife in the NT is not about dying and going to heaven, but about resurrection. It’s our final destination and destiny, it’s the future that can really give us hope that one day disease, decay, and death, suffering, sin, and sorrow will be no more. And that’s so much more than disembodied existence in heaven. It’s the final proof that, as Dylan Thomas once said, ‘and death shall have no dominion’.