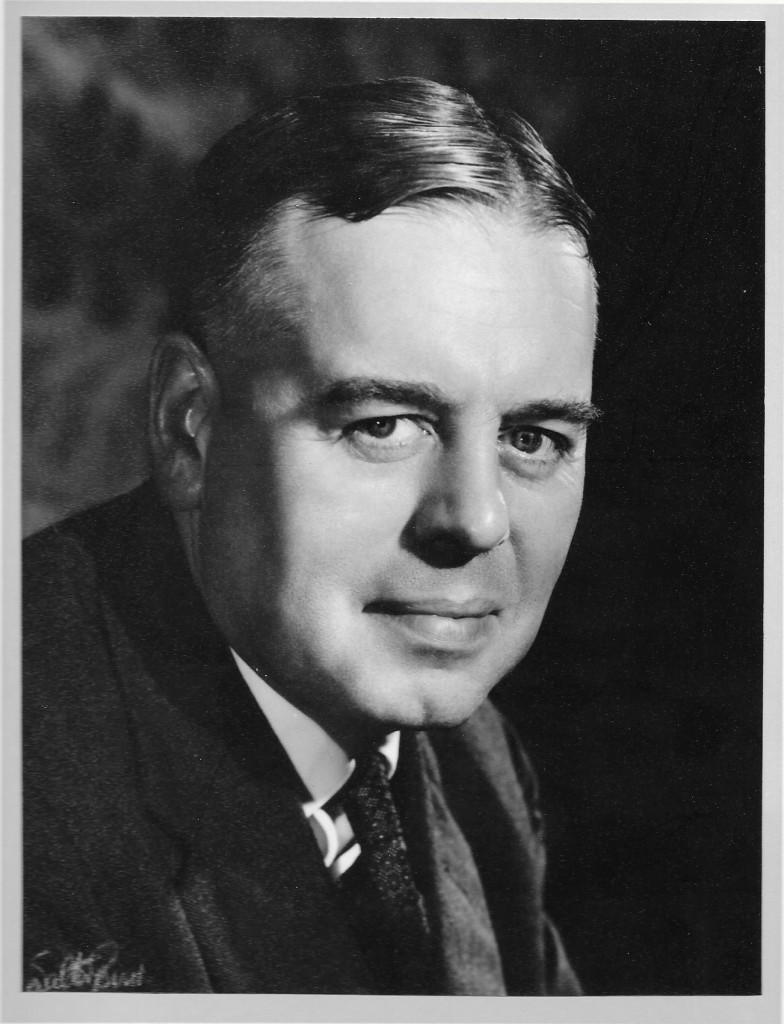

The new Barrett sermons volume is out, with great thanks to Kathy Armistead and Jennifer Rogers, and since this is the month in which we celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, I thought it would be appropriate to present here some lecture material my mentor, C.K. Barrett gave on Luther and his influence on Wesley.

—-

Luther was born in 1483, the son of a prosperous miner. The impression we get is that he grew up in a good, but cold home. but there are indications that the parents were proud of their brilliant and lively young man as a law student, taking Latin at Magdeburg and Eisenach University in Erfurt. He took the B.A. in 1502 and the M.A. in 1505. He was on a path to become a wealthy lawyer, the world at his feet. In 1505 July 2 he had a crisis, cried out ‘St. Anne help me and I will become a monk.’ Luther gave up all that for the Augustinian convent. Why? The death of a close friend may have something to do with it perhaps, but the main reason expressed was ‘to get rid of my sins, and find peace. To find a gracious God.’ July 17th he entered the cloister. May 1507 he said his first Mass, which was nearly a catastrophe. When questioned about his father he replied ‘Have you not read Christ’s words ‘Here are your father and mother?’ He prayed that the call to be a monk was not a delusion of the Devil. The relevancy of his quest depends on whether there is such a gracious God. If there is, there is nothing more relevant. To this end, Luther did his best to make religion work for him, but it did not. Here in any case was a young man who took God seriously.

Luther seems to have been instructed as follows ‘if you are penitent, God will pardon your sins.’ But the question for Luther was— How can I be penitent enough? How can I be sure I’ve confessed everything? Not satisfied with that he consulted his superior Staupitz to see if he knew a better way. Staupitz advice was both theoretical (‘fly to the wounds of Jesus’) and practical (take up a lectureship in Scripture at Wittenburg. And Luther followed this advice.

From 1513-15 he lectured on the Psalms. In 1515-16 he lectured on Romans. In 1516-17 he lectured on Galatians. In 1517 on Hebrews. I pick out two points from these lectures, for in the Bible he found the peace he was looking for. From Ps. 22.1, which Christ quotes on the cross, Luther deduced that all the desolation and the terrors he himself had experienced, Christ also had experienced too “and for me!” The wrath of God? Yes, but in truth it is his love in sending his Son to die for me. From Rom. 1.17 arises the question How can God’s righteousness (justitia) be Gospel? It is God’s gift– his justifying, saving righteousness. Here I break off the story, and urge you to read it in Roland Bainton’s great biography of Luther. What is obvious is the importance of the Word of God in Luther’s transformation. It is just as important for the English version of Lutheranism, by which I mean Methodism.

You know the ‘here I stand’ story of Luther before the Diet of Worms, then there is the kidnapping and Luther finds himself at Wartburg Castle and there he begins his Scripture translations in 1522. Scripture becomes the primary foundation, and in it he discovers saving faith. He calls it ‘the crib in which Christ is laid’. He comes to believe that Preaching the Gospel creates the Church. The Word is active and alive and changes people. Preaching must expound the Scriptures. This is not bibliolatry. It is asking ‘what is apostolic?’ Wesley was to call himself ‘homo unius libri’ a man of one book, very much in the footsteps of Luther. But Luther’s legacy also involved emphasizing the importance of sound doctrine.

Luther of course insisted on ‘justification’. A very large word for a large concept. It starts by taking God and his righteousness seriously. Picture a law court, with a code to judge by, and witnesses to prove. But the verdict on the sinner is not guilty! In his dream Luther saw the Judge is now his friend. This judgment is not a fiction or artifice but a creative act. The Judge is a friend of sinners. This is primarily because it is where even God must begin. It is an anticipation of the Last Judgment, and it leads to a universal priesthood. The whole Body shares Christ’s priesthood. All are priests and kings. This is not about ministers, who have the specific job of preaching, and none exalted that role more than Luther. But Priesthood is not a category applied to preachers.

How does Methodism stand today in relation to this? John Wesley also insisted on justification, in season and out. He practiced the universal priesthood better than most. Today there is much to make one wonder about Methodism. Do we hope to achieve salvation by our works? Reinstitute sacramental clericalism? Why do we allow local preachers to preach and not serve Communion? I do not wish to see people standing up for their rights, I just want them to be given the opportunity for service.

Luther also insisted on assurance of salvation, given by the free grace of God, an assurance for all. With these two emphases, justification by faith alone and assurance of salvation Luther put the church back on the right track. How did this help Wesley?

We are all familiar, perhaps too familiar with the Aldersgate story from May 24th 1738. In the little society meeting off Aldersgate St. someone was reading from Luther’s Preface to the Romans at about 8.45 at night. He was reading the passage about the change God works in the heart by faith. ‘It is a living busy active powerful thing is faith, so that it is impossible that it should not be doing good.’ The answer to both Luther’s and Wesley’s quest for assurance was not painful religious striving, but faith. Not just any kind of faith but ‘I felt I did trust Christ, Christ alone, for salvation.’ It is the solus Christus of the Reformation that Wesley is affirming. Faith can forget itself because it is focused on Christ.

There is much more along these lines in Barrett’s sermon ‘Faith and Works: Wesley and Luther’ Romans 5.1-11 which can be found in The Sermons of C.K. and Fred Barrett: Luminescence Vol. 2, pp. 16-20. I highly commend those two volumes to you, with a third forthcoming. In my judgment they are the best combination of Biblical and Wesleyan preaching of the whole 20th century and the beginning of this one. CKB preached some 5,600 times between 1932-2009 and we owe him a great debt. He was a child of the Reformation, not least in both his beliefs and his diligent practice of the art of preaching.