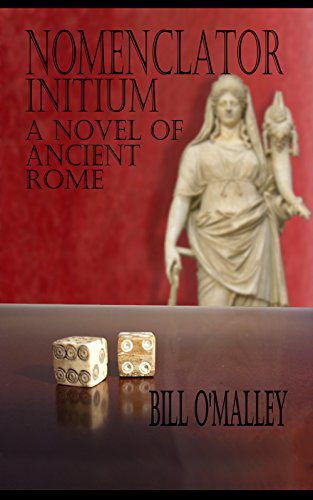

It is no secret I enjoy novels about ancient Rome set in or around the NT period. I’ve read all of the novels of Stephen Saylor, Colleen McCullough, and Lindsey Davis and now have found a new writer, Bill O’Malley who has recently published (apparently self-published) his first novel that involves two of my favorite ancient figures— Julius Caesar and Lucius Seneca. Since these two men lived in very different eras of Roman history, the bridge between them is made by having a really ancient ‘nomenclator’ named Polybius who had been the slave of Caesar tell his tale in his 90s to a very young Seneca in A.D. 15, remembering that Caesar died on ‘the ides of March’ 44 B.C. The story involves a very long conversation between these two men, and here is a summary of the novel itself—“The first in a series of four novels, Nomenclator Initium is a moving tale of love, loss, friendship, and adventure, all set against the background of ancient Rome in all her glory and splendor and squalor. The story is sometimes tragic and moving and sometimes full of adventure. This is the tale of Polybius, a slave since birth, and his longing for freedom and family. A bright, precocious boy, he rises from working in his first master’s copy shop to being named nomenclator and chief confidant of Julius Caesar at the beginning of his career.” (The book is 485 pages long, and $14.99 on Amazon). The story in this volume goes only as far as Caesar’s departure to serve as governor in Hispania Ulterior in 62 B.C.

What, you may ask is a ‘nomenclator’? This Latin word, from which we derive the English word nomenclature, refers to a person, normally a slave but it could be a freedman, who remembers names, dates, persons, etc. for his master. He’s a sort of living, breathing Wikipedia app, or Rolodex file for the ‘great man’. The action of the novel takes place not in the foreground in the time it is told, but in the telling by Polybius, remembering a time long ago, indeed Polybius goes all the way back to the birth of Caesar in 100 B.C. but focuses on his young adult life after Caesar’s father unexpectedly died in the 80s.

Despite too many typos which need to be cleaned up, O’Malley knows his subject well and tells a good tale. Especially effective is the recounting of the Catiline conspiracy and its aftermath and the Bona Dea scandal which led to Caesar’s abrupt divorce of Pompeia. O’Malley understands well how different the ethics of ancient pagans was from those of modern Christians, for example, and how much that world was ruled more by considerations of honor and shame, than by sexual or political morality we might approve of today. Caesar the lothario who beds many other men’s wives is on full display, as well as the permissiveness in regard to homosexual encounters as well, for men at least. These were not merely encounters of elite men with boys or slaves, as is sometimes suggested.

Historical novels of this sort are helpful in providing an understanding of the Greco-Roman context and ethos in which Paul and his co-workers operated on a mission to change the religious and moral orientation of that ancient world. I look forward to further installments in this series.