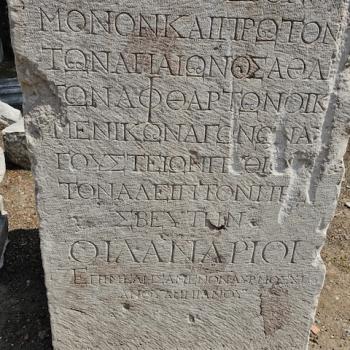

BEN: One of the real strengths of this book is the detailed treatment of the theology in 1 Peter, and I especially appreciated the highlighting of Peters focus on the stone language, the suffering servant language, and his ecclesiological language. I suspect that Peter is not using the term ‘ekklesia’ because he can use the OT language easily since he is mainly addressing Jews not Gentiles, whereas Paul, who may be the first to talk about the ‘ekklesia of God’ uses a term Greek speakers would be very familiar with all the way back to the democratic assemblies in the golden age of Athens. You also rightly stress how Christ becomes a paradigm of triumph through suffering for the converts in Asia who are experiencing some suffering and persecution. This is helpful. They were already marginalized as ‘resident aliens’, for they or their ancestors had in fact been deported to the area to work there by a series of Roman rulers, and before than the Antiochians. Now, their Christian faith had even further marginalized them in the eyes of there pagan neighbors. It was a precarious situation. Talk to us about the Petrine theology of suffering and endurance and why that is important in our context when Evangelicals are constantly talking about avoiding suffering through the rapture etc.

GENE: Well, the Hellenistic elements are quite present in 1 Peter as well even though Peter does not use the word ekklesia to describe the church. Let me recall the domestic code with its stress on subordination (which, by the way, merits considerable discussion – Elliott’s commentary is a good starting point). I argue that the alien language was commonly used of proselytes and likely marks the readers as gentiles (I see that eyebrow…).

A student of mine in Costa Rica, Geancarlo, went out from our seminary to be a missionary in the Middle East. He and his family experienced a tremendous amount to rejection as he shared the Good News of Jesus Christ. His children were even stoned on the way to school. He returned to Costa Rica and complained bitterly that nobody had taught him about suffering as a Christian. My response was simple: “Geanca, you weren’t in my classes.” Peter’s first epistle, along with his proclamation in Mark, offer us the core of a Christian theology of suffering. Following the Crucified One means to share or participate in his sufferings (1 Pet. 4.13). In 1 Peter the apostle talks to the bewildered Christian communities about suffering as they bear witness to Christ in their towns and villages. They endured social ostracism through public verbal and physical abuse, so much so that Peter needs to call them to not buckle under the weight of dishonor – no small thing in an honor/shame culture. Peter does not encourage the Christians to “run away, run away,” Monty Python style, but exhorts them not to be ashamed since they have entered into Christ’s sufferings. He calls them to “do good,” social good, in that hostile society so that those who oppose them will be ashamed (2.11-17).

My students and I have talked much about how to live as Christians in this age. Engaging in culture wars is not the way to go, at least if we seek to follow Peter’s words about witness. Christian work in the world is about giving verbal witness (2.9) but also means shunning retaliation and doing good to those who speak evil of and persecute you. Peter lays out a pattern for being in the world that he had learned from Jesus’ teaching and example. No guns, no violence, no returning evil for evil, no reviling or slandering those who oppose us, but doing good in society, being social benefactors who attend to the needs of those around them, seeking the welfare of the city, as God said through Jeremiah (29.7).