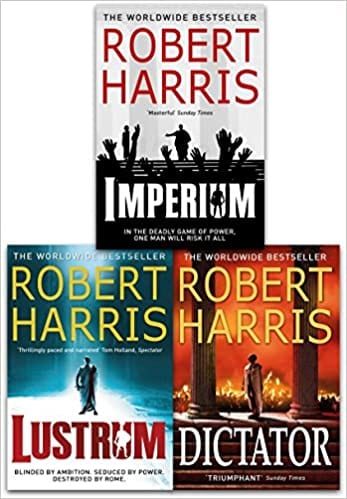

A lustrum by definition is a period of five years. Yet it also can mean an expiatory sacrifice offered once every five years by the censor. Oddly, it can also mean debauchery, or in the plural the lair of a wild beast. All of these definitions come into play in this novel, the second of the three volumes of Robert Harris’ trilogy about Cicero, for at the end of tale Caesar is going off to serve five years in Gaul, Clodius is out for blood, specifically Cicero’s and is running amuck in Rome, and Pompey has married the fourteen year old daughter of Caesar, named Julia, a girl he could be the grandfather of. This novel is longer by a good bit than either Imperium which precedes it, or Dictator which follows it. It is a rich full telling of the rise of Caesar in the 60s B.C. and what Cicero tried to do to contain, confine, or even convict Caesar of crimes in the Catalina conspiracy. Once again, the tale is told from the vantage point of Tiro, Cicero’s remarkable scribe and slave, and really his best and most loyal friend as well.

Harris has excellent powers of description, and knows very well how to craft a story so that it has surprise and suspense. Though this novel is long, it never lacks for interest. One of things one learns to do in reading these novels about ancient Rome is one realizes that one must not evaluate ancient Romans by later Christian standards. They lived by their own moral codes in which obtaining honor and avoiding shame was more important than always telling the truth, and humility was not really much seen as a virtue. Rather the word for it Greek refers to behaving like a slave, being obsequious etc. Even the best of the Romans, even the most principled like Cato the Stoic, or to a lesser degree Cicero, do not come across as persons of unswerving values that we might affirm today. There were world was different, and their ethics different. And all of these ‘great men’ had great egos as well, whether we are referring to Caesar, Pompey, Clodius, Cicero, or others. Their societies were highly stratified with the rich patricians at the top, and the poor plebs below them. The greatest shock to this system is not merely the meglomania of Caesar and his attempt to dismantle the Republic and turn it into a dictatorship, but the fact that a patrician like Clodius would give up his patrician status to become a pleb, and then raise a mob against all patricians and their ways.

There are lessons to be learned from this novel in our precarious position today in America when we have a President who would prefer to be a dictator than someone who practices the art of compromise and works with the Congress, and when we have representatives of both parties spouting fake news, conspiracy theories, whilst working to disenfranchise some voters or gerrymander some districts, and in general wipe out the principle of one man one vote. We too are losing our Republic in these days. And some would say that our current plague is God saying ‘a plague on both your houses’, but I would suggest that’s going too far.

The old maxim ‘those who refuse to learn from history are doomed to repeat it’ is a good one for our day, and there is much to be learned from reading Lustrum of relevance to our current malaise. I commend it to you, whether you care about history, or about now, or about both.