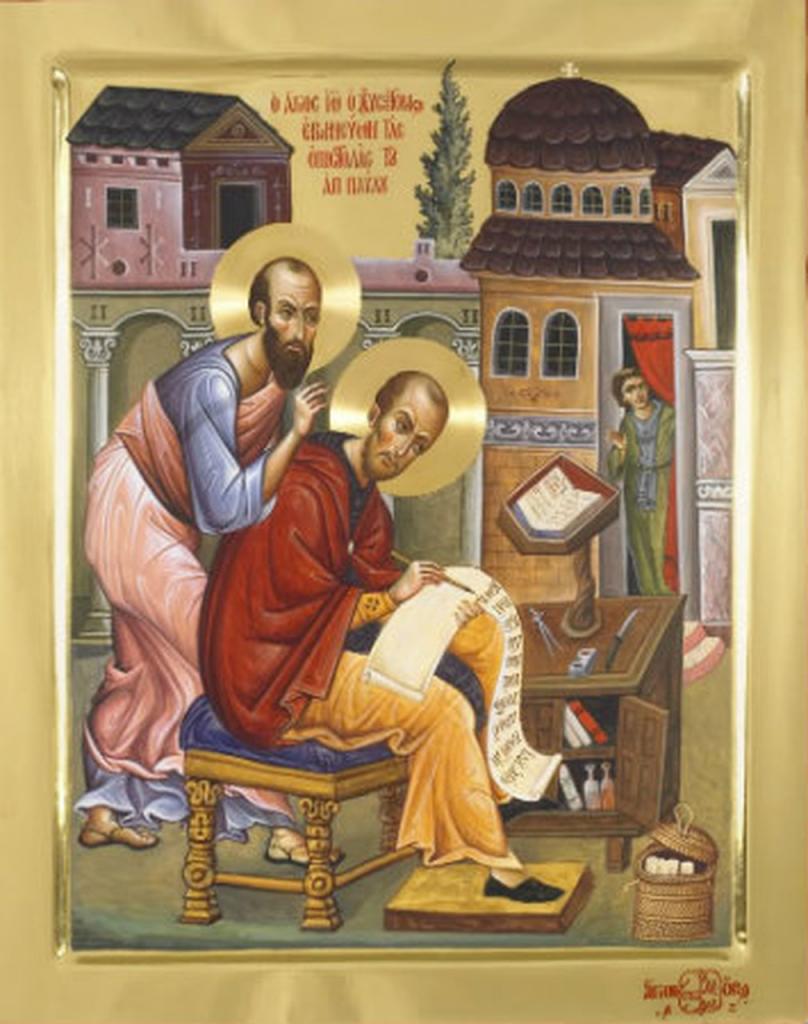

The picture above is of a famous icon depicting St. Paul inspiring the writings of his biggest fan, John Chrysostom. Fan is probably not too strong a word. Chrysostom even preached whole sermons on the merits and positive example of Paul. And John modeled himself after Paul in numerous ways, for example in his use of rhetoric, his deep devotion to understanding the Scriptures, his self-sacrificial conduct, his disdain for ‘all things in excess’— food, drink, clothing, etc. Margaret Mitchell’s now classic study The Heavenly Trumpet provides us with a very vivid picture of John, and his admiration for and following of Paul.

We now have a small but quite helpful study by Gerald Bray, research professor at Beeson Divinity School about John ‘Goldenmouth’ (which is what Chrysostom means, the latter being what others called him once they heard his remarkable preaching). The study focuses on John as pastor and preacher, but along the way we learn a good deal about John’s theological and ethical views, his hermeneutical approach to Scripture, and his actual interpretation of key texts. For my money, Chrysostom was the best of the early exegetes of the NT, focusing on the surface meaning of texts, rather than turning them into allegories ala Philo or Origen. Chrysostom was a native of Antioch post-Constantine who came of age in the last half of the 4th century when Christianity was on the way to becoming the state religion. He wrote post Council of Nicaea but pre Council of Chalcedon and the Nicene creed. Nevertheless, he was thoroughly Trinitarian in his theology.

Bray’s little study is easy to read, and serves as a good into to the man and his ministry and thought world. One of the major takeaways is Chrysostom’s emphasis on the principle of ‘accommodation’. By this, Chrysostom meant that God’s revelation is distilled down to a level that human beings can understand, so for example God often speaks using analogies, metaphors and the like to make clear his meaning. Similarly, Chrysostom as a pastor in Antioch and later in Constantinople followed this same principle, preaching in ordinary language and trying to make sure his sermons were words on target for the average Christian of his day. Bray is right as well that despite Chrysostom being thoroughly grounded in Scripture both the OT and the NT (he wrote the first full commentary on the Gospel of Matthew is church history) he did not escape some of the influences of his Greco-Roman culture, affirming body/soul dualism, but not at the expense of saying that materiality is inherently evil or tainted, as the Gnostics did. No says Chrysostom Genesis says it is all very good, all of creation is good. But Chrysostom was also an ascetic, with a deficient view of the goodness of human sexual expression in the context of marriage, and he thought he was following Paul in these views. His exegesis of Genesis’ ‘they were naked and unashamed’ is rather humorous, suggesting that actually Adam and Eve didn’t see each other naked, for God’s glory covered them. This prudery the author of Genesis knows nothing about. Nevertheless, there are many profound insights in Chrysostom’s commentaries on Genesis, Isaiah, Matthew and John and the Pauline Epistles (he wrote a commentary on all of those, including Hebrews which John thought Paul wrote).

Bray is a very able exponent and advocate for Chrysostom, and those wanting more should turn to his volume on Romans in the Ancient Christian Commentators series, which he edited. In it there is plenty of engagement with Chrysostom’s most famous commentary. I could have wished this book by Bray was at least twice as long as it was, as we have too few good resources on John, and Bray knows his subject matter in great depth and with good insights. For example, consider Chrysostom remark about why Jesus submitted to baptism by John the Baptizer. Jesus said it was to ‘fulfill all righteousness’. After the usual remark about Christ fulfilling the Law, Chrysostom adds, but the law doesn’t contain all positive righteousness. Jesus went beyond just fulfilling Scripture to depicting what an even greater and higher righteousness in a human life should look like, a righteousness that did not come from obedience to the Mosaic law, but rather went beyond it. There is much to ponder in this little book, and I commend it to you.