More of Philip Jenkins’ reflections…….

Of Demons Laying Traps

A Psalm 91 reference here would also contextualize Jesus’s foes quite powerfully. At the time, this was the main text for use in spiritual warfare and demon-fighting, and was used thus at Qumran. The hunter, or fowler, was the Devil, or a demon. So in this reading, the Pharisees were demonic. That reading is reflected in another (mis)translation, where is our Psalm 91.6 talks about “the plague that destroys at midday.” But the Septuagint renders this as “the noonday demon,” daimoniou. The whole Septuagint version of Psalm 91 is highly demonic in a way the Hebrew just is not, and nor are our modern versions.

Matthew 22.15 has a close verbal echo in 12.14, when again the Pharisees plot together against Jesus, in this case to destroy him rather than to trap him. That earlier line in chapter 12 comes immediately before a heated row with the Pharisees about casting out demons, daimonia, invoking Beelzebub, and other appropriately diabolical themes (12.22-29). That in turn leads into a passage about good and bad words, by which one many be condemned or acquitted (12.33-37). The whole passage offers a neat parallel and prefiguring of the chapter 22 episode I have discussed, and at every point, the Septuagint’s Psalm 91 is lurking in the background.

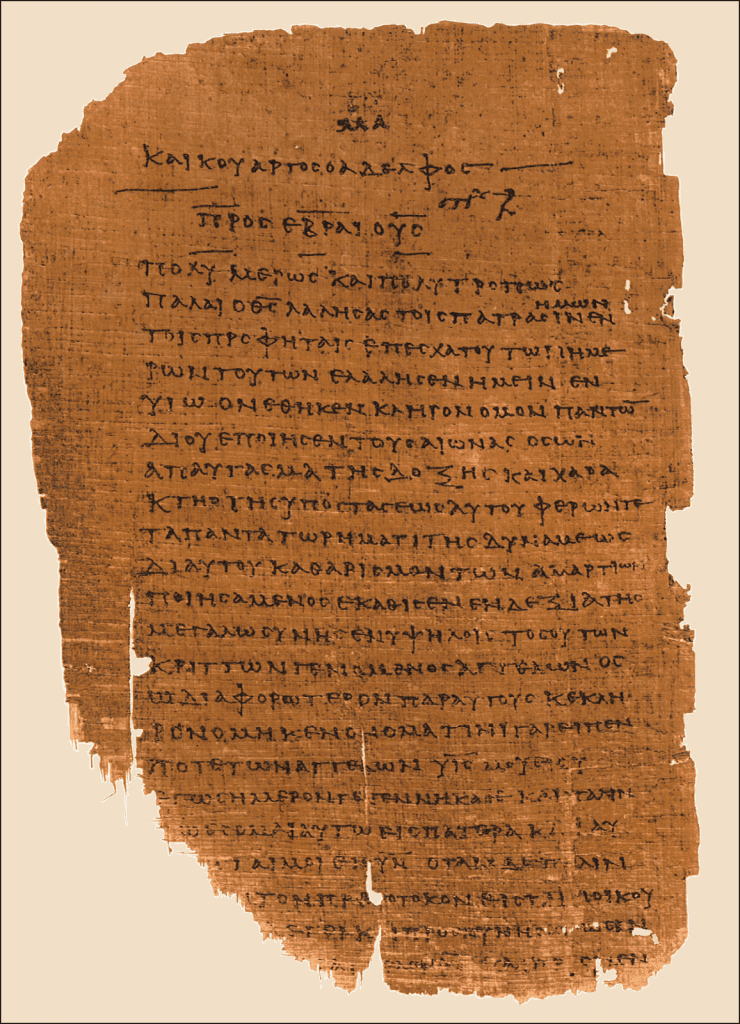

That is one small and specific example, but issues like this run throughout the New Testament. If you don’t refer to the Septuagint, for instance, then the Epistle to the Romans can sound like a horrible mishmash of half-remembered misquotations from the Old Testament. But in fact, it’s anything but that. Once you realize how thoroughly acquainted Paul was with the Septuagint, things make a lot more sense.

How We Lost the Septuagint, and Why It Matters

It also helps to recall what that Septuagint actually is. We usually speak of it as a flawed or tendentious version of a pristine Hebrew original, and I have done something like that here. But the standard Masoretic Hebrew text did not emerge in final form until much later, and did not achieve canonical status for centuries. The Septuagint reflects rival Hebrew readings that were quite standard at the time of the translation, and which are, for instance, often reflected at Qumran. The Septuagint is way more respectable than we often think, and it is a real shame that we have lost it in mainstream usage.

In the sixteenth century, Christian churches rediscovered Hebrew, and they rapidly applied that skill to reading the Old Testament. That event created an unbridgeable linguistic gulf between all later Christian generations and the world of the New Testament and the Church Fathers. If we know the Old Testament in a reliable translation from the Hebrew, like the NIV, that is a treasure to have, but often, the readings we find there are simply not the ones that the early Church knew. The problem for modern readers is that our modern Old Testament translations are just too accurate to let us understand the church’s earliest thinking.

So if we do have to choose an Old Testament version to use as background for studying the New Testament, if we absolutely must choose between a scholarly rendering of the Hebrew Masoretic text, and the error-prone Septuagint … Then, to adapt the title of a film I love dearly: Let The Wrong One In.

Of Asps, and Even More Asps

On a trivia note, I offer a quick story of “those wacky translators at work.” As part of my Psalm 91 wok, I have been looking at Isaiah 11.8, which is part of one of the most famous passages in the Hebrew Bible, portraying the peace and harmony of the messianic age. In the NIV, verse 8 reads as follows: “The infant will play near the cobra’s den, and the young child will put its hand into the viper’s nest.” In the Hebrew, there are two not too common words for types of venomous snake, respectively pethen, and the more obscure tsepha’. There is a lot of debate about exactly what each refers to, but the point is that there are two different very dangerous snakes, which are juxtaposed in poetic balance. This is the classic parallelism that we so often find throughout the psalms.

Now move forward to (probably) Alexandria around 200 BC, where a translator was working on the Greek translation. He decided easily enough that the first beast was an asp. He then sat long and hard looking at his sources and tried to work out what a tsepha’ might look like, the only minimum requirement being that it has to be something, anything, except an asp, so as not to duplicate the word. Parallelism had to be preserved. At some point, he concluded, “It’s just a snake. I have a lot of work to do.” The Septuagint as we have it thus reads “And the young child shall put his hand over the hole of the aspidon, asp, and on the lair of the offspring of aspidon, asps.” Sometimes, you can tell when translators have just had a long day.