The Christology of Mark’s Gospel has been a flashpoint for scholarly debate for a very long time indeed, not least because it is in all likelihood the earliest of the canonical Gospels. It has especially been fodder for those who subscribe to the notion of some sort of dramatic evolution of Christological thinking beginning with low Christology (Jesus the divinely empowered prophet or sage, but nonetheless purely human) to high Christology (Jesus as both God and human being), with Mark being more nearly in the former category and John being more nearly in the latter category, with Matthew and Luke somewhere in between.

The problems with this whole way of thinking, is of course that Paul’s undisputed letters are chronologically prior to these Gospels in all likelihood, and in various ways, they reflect a very high Christology indeed, including the Son of God’s pre-existence (see Phil. 2) and a willingness to call Jesus God in various ways (see e.g. Rom. 9.5). In other words, historically speaking high Christology already existed among some early Christians, prior to the time when Mark wrote his Gospel in the late 60s or early 70s A.D. Unless one thinks the Gospel writers lived in seclusion from the rest of the Jesus movement and wrote their Gospels in splendid isolation and ignorance of what various of the apostles thought about Jesus, such facts are not irrelevant to the discussion of Mark’s Christology. While clearly there is development over time in the way Jesus was viewed, it does not involve an easy evolutionary spiral from low to high Christology. Equally clearly, it is wrong to anachronistically read the later views from Nicea or Chalcedon back into the discussions we find in the NT documents about Christ.

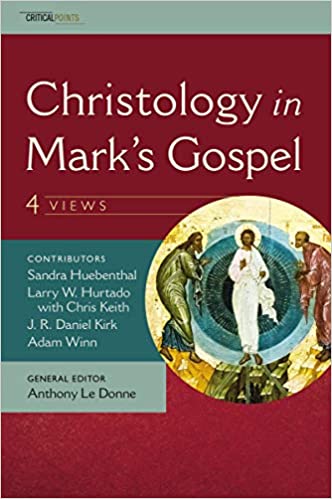

This particular book about Mark’s Christology involves a genuine scholarly spectrum of views on the subject, and it differs from various earlier 4 views volumes you may remember being published by Zondervan previously. This one clearly doesn’t involve 4 Evangelicals debating things with each other. Rather it reflects a considerably broader spectrum of views and that in itself is not a bad thing at all. Zondervan, like Baker, has decided to have a wing of their publishing operation called Zondervan Academic which allows for such breadth of discussion.

Larry Hurtado, of blessed memory, takes a historian’s approach to the matter especially in light of his previous work on early Christian devotion and devotional practices involving Jesus. Adam Winn wants to read Mark especially in light of the parables of Enoch, and the idea of ‘two powers in heaven’ and wants to suggest that Mark presents Jesus as ‘the imminent manifestation of YHWH’. Sandra Huebenthal takes a narratological text centered approach, indebted to a lot of the recent discussion in Europe, and Daniel Kirk offers a consistent presentation of Jesus as ‘the Human One’ which is the way he wants to render ‘Son of Man’.

And here is where I say that none of these presentations are entirely satisfactory as far as I am concerned. For example, none of them reflect to any significant view on what Mark’s presentation of Christ may tell us about the historical Jesus and his views of himself. Quite surprisingly, nothing is said about the fact that the two phrases constantly found on Jesus’ lips— Son of Man and Kingdom of God, might tell us about both Jesus’ self-understanding and Mark’s Christology, especially since one of the most widely agreed verdicts of historical Jesus work done in the past half century is that the historical Jesus really did use those phrases. Even more surprising is that in none of these 4 presentations is there any real discussion of the fact that the only place in the OT where you find both the notion of the Son of Man and of God’s everlasting Kingdom together is in Daniel 7, a text all these scholars admit Mark is indebted to in his presentation of Christology in general and Jesus in particular. The end result of that oversight is that various errors in the discussion of Mark’s Christology could have been avoided, but weren’t.

One of things I do indeed like about this book is that each of the participants gets to critique the other three, and then after that there is a rejoinder by the person who wrote essay. The discussions are fruitful, not pure polemics, and we get to see the weaknesses and strengths of the various views as a result. This is quite helpful.

A few further observations are in order. While it is a good thing to focus on the actual content of Mark in these discussions and not on theories or collateral matters, a text without a context is just a pretext for whatever you want it to mean, frankly. And sometimes a narratological approach neglects or even ignores the context. I am reminded of what Jimmy Dunn used to say— ‘texts don’t have theologies, people do’. Exactly.

The text doesn’t stand alone and was not intended to stand alone, and so historical reconstruction of the setting, audience, and yes, the possible author is important for understanding the text. I am myself quite tired of hearing about the so-called intentional fallacy, to which I respond— texts don’t have intentions, people do. Figuring out what an author means by what he says is part of the process of doing a critical and historically responsible evaluation of an ancient historical text as influential as Mark’s has been. The text must be evaluated in the context of the larger Jesus movement and its other writing contributors, comparing and contrasting what is said. Obviously, this is part of doing Synoptic Gospels study. And of course it is also critical to evaluate Mark in light of early Jewish literature in general and the Hebrew Scriptures as well.

A second thing, which I have dealt with at some length in my Isaiah Old and New and the two related volumes is that intertextuality studies are regularly in danger of capitulating to a ‘meaning is in the eye of the beholder’ approach. This too is problematic from the point of view of epistemology. The audience didn’t write the text in question, and their reception or reaction to it is a separate matter from the meaning the writer encoded into the text itself. Texts may have various kinds of significances for differing readers or hearers, but the meaning of the text has been determined by the person who wrote it, not by the audience who reacted to it positively or negatively. In this case I am talking not about open-ended modern or ancient poetry that sometimes is like a cloud in which one can see various things if one has a good imagination, but rather about ancient prose works, like the Gospels which take the form of ancient biographies about someone other than the author himself.

A third thing is that try as they might, these 4 scholars sometimes talk past one another. This seems especially to happen when it comes to the essay of Adam Winn who keeps wanting to suggest that Jesus is the imminent manifestation of YHWH, and this despite the clear distinction between the Son of Man and the Ancient Days in Daniel 7, and also between Jesus and that voice from above who calls him his beloved Son and to whom Jesus prays as Father/Abba.

But at the same time equally unhelpful is the idea that Jesus is merely God’s human representative or agent on earth, like previous ones. Previous one’s however did not have the capacity to say what was and was not suitable behavior on the Sabbath from a divine point of view, nor to walk on water, nor to be called God’s unique beloved Son, nor to die as a ransom for the many, and so one. And frankly the phrase ‘the Son of Man’ in Mark’s Gospel does not merely mean ‘a man like me’ or ‘the human one’. It is a deliberate echo of Dan. 7, and as C.F.D. Moule said long ago— the definite article found before the phrase on Jesus’ lips over and over again points to ‘the aforementioned Son of Man in Daniel 7’ as several texts in Mark make abundantly clear. Jesus is clearly unlike any other human being if Dan. 7 is how he viewed himself, for in that text the one like a Son of Man is asked to rule in God’s kingdom forever over everyone not just Israel, and is said to be an object of worship. The contrast could hardly be more dramatic when one compares Dan. 7 with 2 Sam. 7.12ff. which speaks of dynastic succession of the line of King David. By contrast the one like a Son of Man will rule forever and over everyone. Notice as well that Jesus nowhere calls himself Son of David in Mark, indeed he deliberately questions, on the basis of Ps. 110.1ff. whether calling the messiah Son of David is adequate, when in fact David the Psalmist calls him Lord!!

There is much more that could be said, and I was quite sad reading my old friend Larry Hurtado’s contribution to this volume, apparently the last scholarly work he did before he passed away two years ago now. There is so much more he could have added to the conversation in various historically important ways. We sorely miss you Larry and your important contributions to the study of the NT. Thank goodness we have many good books from you.

Suffice it to say here that a measure of a good book is that it teases the mind into active thought. This book has certainly done that in my case, and is well worth reading, as long as one doesn’t take everything said in the book as the Gospel about Mark’s Gospel.