Q. And not just any sort of ‘church’ showed up but a highly patriarchal one justified by what Jesus is attested to have said to Peter at Caesarea Philippi in Matthew (but not in Mark or Luke). Recently, in a commentary on Luke which I did with A.J. Levine for Cambridge (the first ever commentary by Jewish and Christian persons together on a Gospel) and we had a big debate about the role of women mentioned in Lk. 8.1-3— are they portrayed merely as enablers and patronesses, or as actual traveling disciples— I said they were both, as the end of the story in Lk. 23-24 makes clear. They were vital witnesses, about the teaching of Jesus, and were last at the cross, first at the tomb, first to see the risen Jesus. How would you view this matter? message. A.J. demurred from this sort of reading of the data, and thought they were just patronesses. How would you view this matter?

A. I agree with you, I think. Jesus’ engagement with women, for example with Mary and Martha and with the Samaritan woman in John 4, is strikingly positive, and the engagement is not just in terms of patronage and hospitality but in terms of teaching and theology. There are hints of them sharing in ‘evangelism’, informally at least, bringing the good news to others. It is Paul who is often cited as the villain when it comes to attitudes to women, but I see Paul as following Jesus and in being very affirmative of women’s equality to men in Christ and of their role in the ministry and life of the church (e.g. in Romans 16). There were some issues, probably with some over-enthusiastic and inappropriate expressions of female ‘liberation’ in the church, and Paul affirms both the created differences of men and women in God’s creation and the importance of order in the church. But once again, Ben, this is more your area than mine, with your two books on women in the early church. I should probably keep my mouth shut in dialoguing with you on this!

Q. The Sermon on the Mount, as you likely know, has been critical in Methodism from the very start with John Wesley. In fact, of the 44 standard sermons of Wesley one fourth of them are on Matt. 5-7 and parallel. This was in part Wesley’s reaction to the lax morals of the church in his day, and more particularly in reaction to some Calvinists whose salvation sola fidei stridency struck Wesley as not in accord with Jesus’ teaching—we need to work out our salvation what God has been working in us to will and to do. In short, sanctification is not entirely sola fidei. Your treatment of Jesus’ ‘Sermon’ is helpful in various ways, and as you say, Jesus is intensifying various of the demands found in the Law of Moses, in regard to marriage and divorce and adultery, but at the same time Jesus is nullifying some of the OT law, for example the permission to use oaths and perhaps the ritual purity laws. What strikes me about this is the sovereign freedom with which he treats the Law, and his conviction that in some ways he is bringing the Law and the Prophets to fulfillment, but in other ways he is offer new teaching that goes beyond Moses, and in some cases indicates some Mosaic Law no longer applies now that the divine saving reign of God is breaking into history. How does one strike the right balance between the theme of fulfillment of the OT Law and new wine for new wineskins, so to speak? Jesus is not simply renewing the old covenant, nor is he simply offering something totally new either. Can you help us make sense of this?

A. I like what I know of Wesley on the Sermon on the Mount; he does not evade its very demanding teaching. The key term is certainly ‘fulfil’, something that Matthew emphasizes throughout his gospel, with Jesus ‘fulfilling’ the story of Israel, the prophetic promises, and the law. When Jesus in Matthew 5:17 says that he has not come to destroy the law and the prophets, but to fulfil them, I see this as a response to an implied criticism of Jesus by his opponents (as well as a response by Matthew to Christians who were justifying their immoral behavior by emphasizing Christian freedom from the law) . Jesus was accused of lawlessness, in relation to his liberal behavior on the Sabbath and his mixing with sinners; he was destroying God’s law and lowering the standards. Matthew 5:17-20 says that far from destroying the law he was ‘fulfilling’ it and bringing the high standards of the kingdom of God, which were higher even than those of the legally scrupulous Pharisees. Then in the verses that follow Jesus’ higher standards are illustrated, with some of the compromises of the law (at least as interpreted by Jesus’ opponents) being rejected, in favour of the perfection appropriate for the kingdom of God, which Jesus was bringing. Nathan Ridlehoover in his book The Lord’s Prayer and the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew’s Gospel brings out the centrality of the Lord’s Prayer in the Sermon, and plausibly argues that the Sermon illustrates out what the Prayer means in action – including ‘Your kingdom come, your will be done on earth as in heaven’.

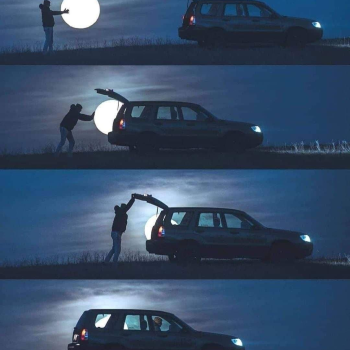

I think that Jesus saw the whole of the Old Testament as looking forward to the coming of the perfect kingdom of God; its coming meant an exciting new day and reality, but not a discarding of the old, rather the arrival of something new superceding it, like a new model of a car superceding its predecessor. I think it was Stephen Travis who in his book Christian Hope and the Future suggested the analogy of a father in the pre-motor-car days promising his son a new horse-drawn carriage; but then the motor car was invented and the father gave him that. It was new, but a superior and appropriate fulfilment of his promise!