Certainly one of the dominant images and passages in the Bible when it comes to the issue of slavery is the storyline in Exodus about the enslaving of the Hebrews, and then their liberation through the efforts of Moses and others. And note that Moses was a reluctant liberator. It was God Almighty who sent Moses back to Egypt with the command to free his chosen people, and Moses was ordered, yes ordered, to confront Pharaoh (probably Ramses II) and to tell him ‘let my people go’. This whole story line should have made clear God’s view of this matter of slavery, and one has to bear in mind that the Bible is not the story of everyone, everywhere. It is rather the story of the origins and salvation history of God’s people, which nonetheless has implications for all other peoples as well (see e.g. Hosea 11ff).

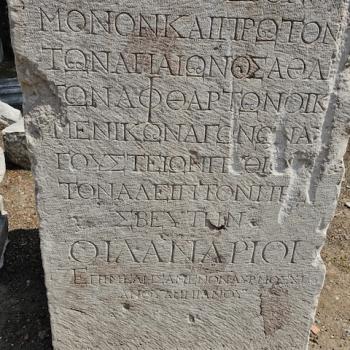

Slavery in the fallen world of the ANE and in the Greco-Roman world was in large measure the basis of the economy which made sure that wealth was in the hands of the few, and poverty was the by word of the many, especially of the slaves. In yet another twist of history, in some cases domestic slaves did much better than the poor free persons, because they had food, shelter, and clothing provided, which resulted in odd epitaphs like ‘being a slave was never a burden or a bad thing for me’. And yet of course slaves, under law, were just chattel, just property to be bought and sold and by and large they had no legal rights at all. So when we read the slave passages in the Bible, and particularly in the NT we need to realize that slavery was a huge long settled institution in the ANE, and also in the Greco-Roman world. There would have been no seven wonders of the world, no pyramids, no temple of Artemis, no mining, no adequate agricultural economy without slavery in that world and the secular laws simply encoded and supported that institution. But what about the Bible?

In the OT we have not only the story of the Exodus, but we have the law of Jubilee both of which show the larger divine design that does not approve of humans enslaving other humans, and seeks to counter these domination systems. And it will be remembered that when Jesus preached his inaugural sermon in Nazareth according to Luke 4 he cited Isaiah which in part says he came to set the captives free, and this was not merely about being free from illness or demon possession. Jesus came to set the eschatological year of Jubilee in motion which is why we actually have people like Paul saying after the fact ‘but in Christ there is neither slave nor free…’ (Gal. 3.28 and compare the parallels). But what was someone like Paul to do with the overwhelming slave situation in his day? One estimate says that up to a third or even a half of the population of a city like Rome were slaves, and Christianity was a tiny minority religion. And there was no democracy only autocracy. How and where could Paul advocate change?

So the strategy to live out the social implications of Gal. 3.28 had to involve working for change in the relationships within the Christian household. It could not be accomplished elsewhere at the outset of the Christian movement. And Paul was practical enough to start with his converts where they were, which is to say, some of the more elite ones already had domestic slaves. So Paul chose to put the leaven of the Gospel of equality and humanity into the Christian household and let that change the domination patterns from within that social context. As I have pointed out in my commentary on Philemon, Colossians, and Ephesians (Eerdmans, 2007), what we see is a progressive working for change. Colossians provides us with first order moral discourse– what Paul would say as an opening salvo to a group he did not personally converted (but seems to have been converted by one of his co-workers, perhaps Tychicus), then in Ephesians we have a circular letter written to some he had converted and some others as well providing second order moral discourse– the conversation continues, and finally in Philemon we have third order moral discourse. What Paul could and would say to someone who had slaves and someone he had personally converted— namely manumit Onesimus, ‘no longer a slave but rather a brother in Christ’. Here Paul boldly tells Philemon that if someone is in Christ, there should be no slave or free. And we know that early Christians in the second century and thereafter regularly would seek to buy slaves out of slavery, trying to implement the Pauline mandate though it was not consistently implemented. But we need to note however the ways Paul was changing the status quo.

Firstly, unlike Greco-Roman household codes which tended to be just advice for the head of the household– the husband, the male parent, the master, Paul by contrast treats wives, children, and slaves as moral agents capable of making moral decisions. He addresses them directly. And the general drift of the threefold exhortations to the head of the household is that Paul is changing the game, wanting the head of the household to NOT follow the advice of Plutarch and others— namely subordinate your wife, children, and slaves, and keep them all in line. In fact he gives three times as many imperatives to the male head of the household than to the other family members. The Colossian household code in the first place ameliorates the approach of the master/husband/father ruling out harsh behavior and discouraging language, even brutal treatment, bearing in mind that masters had previously been told they could beat or even kill their slaves as need be without legal consequences. But let us focus on Col. 4.1 for a minute. As Dr. Murray Vasser has shown in his dissertation the Greek word ἰσότης definitely means equality. It reads ‘Masters, give what is righteous and equality to your slaves, knowing that you also have a master in heaven’. Now this is definitely counter-cultural. Not Plutarch, not Seneca, not Aristotle, not Plato, not anyone was advocating that slaves and masters shared some sort of equality never mind ontological equality. But this is exactly what Paul is saying. He believes we are all created in God’s image. He warns the master that he has a master namely God, and he’d better watch his behavior. And Paul has already told the slave, let your service to the your human master be as services actually to the Lord. Do it as if you were just the Lord’s servant and not part of a fallen human institution.

If we move on to Ephesians, Paul gets even bolder. Not only do we have the commandment in Ephesians 5.21 which says ‘submit to one another out of reverence for Christ’ and this involves ALL members of the household– husbands, wives, children slaves who were all part of household worship. That was the regular practice. But then Paul goes on to add more. He expands the advice in Colossians in important ways…. Note the following. Paul says to the slaves in Ephes. 6—-

7 Serve wholeheartedly, as if you were serving the Lord, not people, 8 because you know that the Lord will reward each one for whatever good they do, whether they are slave or free.

9 And masters, treat your slaves in the same way. Do not threaten them, since you know that he who is both their Master and yours is in heaven, and there is no favoritism with him.’

Paul had already mentioned that God doesn’t judge master or slave with partiality. But here he adds and ‘masters do the same thing as your slaves are doing– namely masters serve your slaves as they serve you bearing in mind God is your master as well as theirs. This is very clearly second order moral discourse, which goes beyond the instructions in Colossians. And then of course there is Philemon. Now all this while, Paul has been working towards Galatians 3.28, gradually implementing change in the Christian household to both domination systems— patriarchy and slavery. He is wise enough to implement change in this way because he knows he must start with his audience where they are and through persuasion and imperatives implement change to these long-standing institutions. But with Philemon, he can be direct, the man who humanly speaking owes Paul his very spiritual life as a Christian— he simply says manumit Onesimus and send him back to me. Now if indeed Onesimus was a runaway slave,, and particularly if he had owed the master anything, besides just his regular work, Paul offered to repay Philemon, but does so tongue in cheek– ‘oh did I mention you Philemon owe me your very everlasting life!’ This is not subtle. By law, Philemon had ever right to beat his returning slave or even ‘terminate’ him. Instead, here he stands in the household meeting with the letter to Philemon in hand which is read out before the whole house church— which puts pressure on Philemon not only to be forgiving and treat Onesimus well but to set him free!! (and on this see my friend Tom Wright’s discussion about Philemon in his Paul and the Faithfulness of God).

Now the upshot of all this is that one cannot fairly treat what the Bible says about slavery as an excuse to say— ‘well the Bible advocates slavery, and therefore we have a right to ignore various of its other ethical teachings, since we moderns now know better’. Of course the irony is that those who say these things think they are being so progressive, and in touch with the times in the West. But in fact, what is happening is they are using such dismissal of the Bible’s ethical teachings and mandates as an excuse to be an advocate for a sort of ethic, including a sexual ethic which has much more in common with first century pagan sexual ethics than with Biblical teaching. It reminds me of that great scene in Shakespeare’s Henry plays, where Prince Hal has been out carousing all night with Falstaff, and the king is staying up late, upset with this behavior, and when they finally arrive home, the king says ‘you think you are so au courant, but in fact you are just committing the oldest kinds of sins in the newest kinds of ways’. I’m afraid that is the state of play in much of American culture today. As it turns out the earliest Christians were more ethical than we are. Like many early Jews, they even abhorred abortion and rescued children who had been exposed and left out to die, which often happened particularly to unwanted baby girls. But that’s a story for another day.