Here’s another helpful post by our colleague Larry Hurtado.

Early Christian Manuscripts and Their Readers

by larryhurtado

A few days ago I noted the publication of a multi-author volume: The Early Text of the New Testament, edited by Charles E. Hill and Michael J. Kruger (Oxford University Press). In this posting I give the gist of my own contribution to that volume: “Manuscripts and the Sociology of Early Christian Reading” (pp. 49-62).

I take my cue from a fascinating article by William A. Johnson (an American papyrologist) in which he contends that the rather severe and demanding features of high-quality ancient Greek literary manuscripts reflect the elite social-settings in which these manuscripts were intended to be read. [William A. Johnson, “Toward a Sociology of Reading in Classical Antiquity,” American Journal of Philology 121 (2000): 593–627.] These manuscripts often have elegant calligraphy, and seem more like works of art than practical texts. They make huge demands on readers, and only those with appropriate training in the ancient world would have been able to cope with them. Johnson argues that this was deliberate, to mark off these manuscripts by/for the elite circles in which they were used.

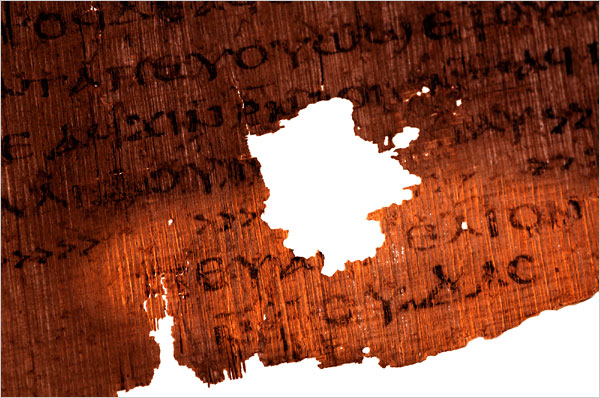

In my study, I consider the physical and visual features typical of earliest NT manuscripts, contending that they too likely reflect the circles in which they were to be read. These features are now increasingly well-known: esp. the preference for the codex format, the general size and spacing of the writing, the use of elementary punctuation, the use of other diacritical marks (e.g., diaeresis) to aid reading, and spaces and/or enlarged letters to signal sense-units. These features lead me to the following proposal:

“If Johnson is correct that the format of the pagan literary

rolls was intended to reflect and affirm the exclusivity of the elite social circles in which they were to be read, then Christian manuscripts (especially those that appear to have been prepared for public reading) typically seem to reflect a very different social setting, perhaps deliberately so. I propose that they reflect a concern to make the texts accessible to a wider range of reader competence, with fewer demands made on readers to engage and deliver

them. In turn, this probably reflects the more socially diverse and inclusive nature of typical early Christian groups. That is, I submit that these early Christian manuscripts are direct evidence and confirmation of the greater social breadth and diversity represented in early Christian circles, in comparison to the elite social circles in which pagan literary texts were more typically read.” (p. 59)

In short, these early NT manuscripts can be taken as physical evidence of the social character of the circles of early Christian readers. This is one example of the point I tried to make in my book, The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins (Eerdmans, 2006), that the physical and visual characteristics of early Christian manuscripts comprise data of relevance for wider historical questions about early Christianity.

I’ve put the pre-publication version of my essay under the “Selected Essay, etc.” tab of this blog site. In addition to my essay, there are twenty other contributions by a galaxy of scholars, covering a wide array of topics. (See my earlier posting for the link to Kruger’s blog posting that includes the table of contents.) Unfortunately, it’s an expensive volume; but it offers a good deal of scholarly value for the price.