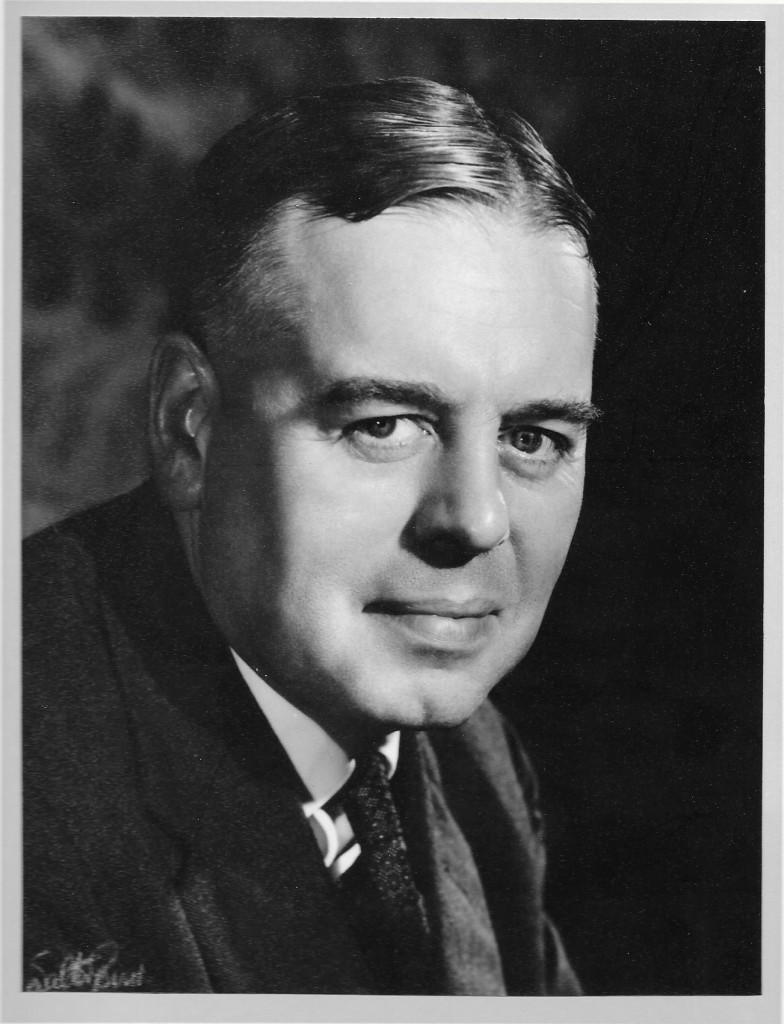

Here’s an excellent post by my friend and colleague Larry Hurtado on the so-called mythical Jesus which I am reposting ten days after he first posted. See what you think.

Why the “Mythical Jesus” Claim Has No Traction with Scholars

by Larry Hurtado

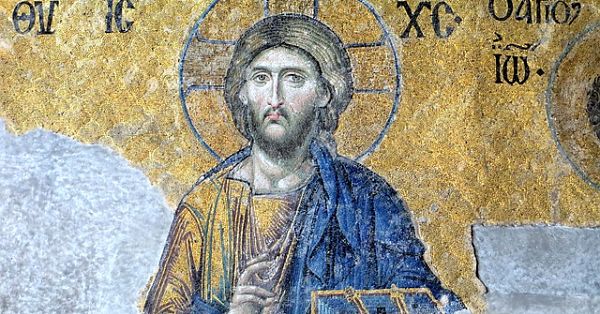

The overwhelming body of scholars, in New Testament, Christian Origins, Ancient History, Ancient Judaism, Roman-era Religion, Archaeology/History of Roman Judea, and a good many related fields as well, hold that there was a first-century Jewish man known as Jesus of Nazareth, that he engaged in an itinerant preaching/prophetic activity in Galilee, that he drew to himself a band of close followers, and that he was executed by the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate.

These same scholars typically recognize also that very quickly after Jesus’ execution there arose among Jesus’ followers the strong conviction that God (the Jewish deity) had raised Jesus from death (based on claims that some of them had seen the risen Jesus). These followers also claimed that God had exalted Jesus to heavenly glory as the validated Messiah, the unique “Son of God,” and “Lord” to whom all creation was now to give obeisance.[i] Whatever they make of these claims, scholars tend to grant that they were made, and were the basis for pretty much all else that followed in the origins of what became Christianity.

The “mythical Jesus” view doesn’t have any traction among the overwhelming number of scholars working in these fields, whether they be declared Christians, Jewish, atheists, or undeclared as to their personal stance. Advocates of the “mythical Jesus” may dismiss this statement, but it ought to count for something if, after some 250 years of critical investigation of the historical figure of Jesus and of Christian Origins, and the due consideration of “mythical Jesus” claims over the last century or more, this spectrum of scholars have judged them unpersuasive (to put it mildly).

The reasons are that advocates of the “mythical Jesus” have failed to demonstrate expertise in the relevant data, and sufficient acquaintance with the methods involved in the analysis of the relevant data, and have failed to show that the dominant scholarly view (that Jesus of Nazareth was a real first-century figure) is incompatible with the data or less secure than the “mythical Jesus” claim. This is true, even of Richard Carrier’s recent mammoth (700+ pages) book, advertised as the first “refereed” book advocating this view.[ii] Advertisements for his book refer to the “assumption” that Jesus lived, but among scholars it’s not an assumption—it’s the fairly settled judgement of scholars based on 250 years of hard work on that and related questions.

You don’t have to read the 700+ pages of Carrier’s book, however, to see if it’s persuasive. To cite an ancient saying, you don’t have to drink the whole of the ocean to judge that it’s salty. Let’s take Carrier’s own summary of his key claims as illustrative of the recent “mythical Jesus” view. I cite from one of his blog-postings in which he states concisely his claims:

“that Christianity may have been started by a revealed [i.e., “mythical”] Jesus rather than a historical Jesus is corroborated by at least three things: the sequence of evidence shows precisely that development (from celestial, revealed Jesus in the Epistles, to a historical ministry in the Gospels decades later), all similar savior cults from the period have the same backstory (a cosmic savior, later historicized), and the original Christian Jesus (in the Epistles of Paul) sounds exactly like the Jewish archangel Jesus, who certainly did not exist. So when it comes to a historical Jesus, maybe we no longer need that hypothesis.”[iii]

Carrier’s three claims actually illustrate his lack of expertise in the relevant field, and show why his “mythical Jesus” doesn’t get much traction among scholars. Let’s start with the third claim. There is no evidence whatsoever of a “Jewish archangel Jesus” in any of the second-temple Jewish evidence. We have references to archangels, to be sure, and with various names such as Michael, Raphael, Yahoel, and Ouriel. We have references to other heavenly beings too, such as the mysterious Melchizedek in the Qumran texts. Indeed, in second-temple Jewish texts and (later) rabbinic texts there is a whole galaxy of named angels and angel ranks.[iv] But, I repeat, there is no such being named “Jesus.” Instead, all second-temple instances of the name are for historical figures.[v] So, the supposed “background” figure for Carrier’s “mythical” Jesus is a chimaera, an illusion in Carrier’s mind based on a lack of first-hand familiarity with the ancient Jewish evidence.[vi]

Now let’s consider his second claim, that “all similar savior cults from the period” feature “a cosmic savior, later historicized.” All? That’s quite a claim! So, for example, Isis? She began as a local Egyptian deity and her cult grew in popularity and distribution across the Roman world in the first century or so AD, but she never came to be treated as a historical woman. How about her Egyptian consort Osiris? Again, a deity who remained . . . a deity, and didn’t get “historicized” as a man of a given date. Mithras? Ditto. Cybele? Ditto. Artemis? Ditto. We could go on, but it would get tedious to do so. Carrier’s cavalier claim is so blatantly fallacious as to astonish anyone acquainted with ancient Roman-era religion.[vii] There is in fact no instance known to me (or to other experts in Roman-era religion) in “all the savior cults of the period” of a deity that across time got transformed into a mortal figure of a specific time and place, such as is alleged happened in the case of Jesus.[viii]

OK, so two strikes already, and one claim yet to consider: a supposed shift from Jesus as “a celestial being” (with no earthly/human existence) in Paul’s letters to “a historical ministry in the Gospels decades later.” The claim reflects a curiously distorted (and simplistic) reading of both bodies of texts. Let’s first look at the NT Gospels.

It’s commonly accepted that the Gospel of John is the latest of them (with differences of scholarly opinion on the literary relationship of GJohn to the others), and that perhaps as much as a decade or more separates the earliest (usually thought to be GMark) from GJohn. So, on Carrier’s claim, we might expect a progressively greater “historicization” of Jesus, and less emphasis on him as “a celestial being,” in GJohn. Which is precisely not the case—actually, the opposite. Most readers of GJohn readily note that, in comparison with the “Synoptic” Gospels, the text makes much more explicit and emphatic Jesus’ heavenly origins, his share in divine glory, etc., right from the opening chapter onward with its reference to the “Logos” as agent of creation and who “became flesh” and “dwelt among us” (1:1-5, 14).

In contrast, GMark simply narrates an account of Jesus’ itinerant ministry of teaching, performing exorcisms and healings, conflicts with critics, and then a lengthy account of his fateful final trip to Jerusalem. There are allusions or hints in GMark that Jesus’ larger identity and significance surpass what the other characters in the account realize, as, e.g., in the cries of recognition by the various demoniacs. But Jesus has a mother, brothers and sisters (3:31-32; 6:3), is portrayed as known local boy in his hometown (6:1-6), and to all the other human characters in the narrative Jesus is variously a prophet, teacher, blasphemer, Messiah, or criminal. Most indicative that the Jesus of GMark is a genuine mortal is the account of his crucifixion, his death, and burial of his “corpse” (Mark’s clinically precise term, 15:45). Whatever his higher significance or transcendent identity, in GMark Jesus is at least quite evidently a real mortal man.[ix] Now, to be sure, GMark (as all the NT Gospels) presupposes that intended readers also regard Jesus as the exalted “Lord”. But the story the Gospels tell emphasizes his historic activity.

As far as the other “Synoptic” Gospels are concerned (GMatthew and GLuke), it’s commonly accepted that they took GMark as inspiration, pattern and key source, each of them, however, producing a distinctive “rendition” (to use a musical term) of the basic narrative. GMatthew, for example, emphasizes Jesus’ Jewishness, adds a birth narrative with lots of allusions/connections to OT texts, and gathers up traditions of Jesus’ teachings into five large discourse blocks. GLuke, writing, it appears, more for a Gentile readership and with more of a nod to generic features of Greek history and biography of the time, inserts dates (3:1-2), and has his own birth narrative and genealogy that links Jesus more to world history.

But the overall point here is that across the years in which the Gospels were composed, there isn’t a trajectory from a “celestial being” with no earthly existence to a “historicized” man. If anything, the emphasis goes in the opposite direction.[x] Certainly, it appears to most scholars that the Gospels reflect the growth of legendary material about Jesus, the birth narratives being a prime example. But legendary embellishment is what happens to high-impact historical figures, and doesn’t signal that the figures are “mythical”.

One further point about the Gospels. Yes, a few decades separate them from the time of Jesus’ execution under Pontius Pilate and from the commonly accepted dates of Paul’s undisputed letters. The NT Gospels, with their bios-shaped narratives do mark a noteworthy development in the history of earliest Christian literature.[xi] But it’s dubious to posit that they mark some major departure theologically from earlier Christian beliefs about Jesus.[xii] Instead, they echo and develop the crucifixion-resurrection focus that we see in our earliest texts, drawing upon the emergent biographical genre to produce a noteworthy “literaturization” of the gospel message.

And some 250 years of critical study of the Gospels has continued to show that they draw upon various earlier sources, both written and oral that had been circulating for decades, including collections of sayings and disputations of Jesus, likely also a body of miracle stories, and narratives of Jesus’ crucifixion. Indeed, the Gospels (especially their variations in their respective accounts) reflect multiple and varied stories and traditions about Jesus that were taught and transmitted across the decades between Jesus’ execution and the composition of these texts. Which means that treating Jesus as the Messiah and exalted Lord whose teachings and earthly actions were significant did not begin with the Gospel writers, but has its roots deeply back into the earlier decades. The earmarks of the traditions on which the Gospel writers drew are there and have been readily perceived by scholars for a long time, whatever differences there are among scholars about precisely the form and extent of these traditions. Treating Jesus as a historical figure didn’t commence late or with the authors of the Gospels.

But, in a sense, the “mythical Jesus” focus on the Gospels is a bit of a red-herring. For the far earlier references to an earthly/mortal Jesus are in the earliest Christian texts extant: the several letters that are commonly undisputed as composed by the Apostle Paul.[xiii] These take us back much earlier, typically dated sometime between the late 40s and the early 60s of the first century. So Carrier’s final claim to consider is whether Paul’s letters reflect a view of Jesus as simply an angelic, “celestial” being with no real historical existence.

Unquestionably, Paul affirms and reflects a “high” view of Jesus, as the true Messiah, the unique Son of God, and the exalted Lord to whom now God requires obeisance by all creation.[xiv] After his initially vigorous opposition to the young Jesus-movement, he had an experience that he regarded a divine revelation, which confirmed to him Jesus’ exalted status and validity as God’s unique “Son” (Galatians 1:14-16), after which he became a trans-national exponent of the claims about Jesus. Corresponding to this, and still more remarkable in light of Paul’s firm Jewish heritage and continuing self-identity, his letters reflect a developed devotional pattern in which the resurrected and exalted Jesus features programmatically along with God as recipient and focus.[xv]

But for Paul and those previous Jesus-followers whom he had initially opposed prior to the “revelation” that turned him in a new direction, Jesus was initially a Jewish male contemporary. It was what they took to be God’s resurrection and exaltation of the crucified Jesus that generated their view of him as having a heavenly status. And, in keeping with ancient apocalyptic logic (final things = first things), God’s heavenly exaltation of him as Messiah and Lord generated the conviction that he had been “there” with God from creation, as “pre-existent”.[xvi] So, there are two major corrections to make to the claim espoused by Carrier.

First, Paul never refers to Jesus as an angel or archangel.[xvii] Indeed, a text such as Romans 8:38-39 seems to make a sharp distinction between angelic powers and the exalted Kyrios Jesus. Moreover, although Paul shares the early Christian notion that the historical figure, Jesus had a heavenly back-story or divine “pre-existence” (e.g., Philippians 2:6-8), this in no way worked against Paul’s view of Jesus as also a real, historical human being.

And, secondly, there is abundant confirmation that for Paul Jesus real historical existence was even crucial. Perhaps the most obvious text to cite is 1 Corinthians 15:1-11, where Paul recites a tradition handed to him and then handed by him to the Corinthians, that recounts Jesus’ death (v. 3), his burial (v. 4), and then also his resurrection and appearances to several named people and a host of unnamed people. Now, whatever one makes of the references to Jesus’ resurrection and post-resurrection appearances, it’s clear that a death and burial requires a mortal person. It would be simply special pleading to try to convert the reference to Jesus’ death and burial into some sort of event in the heavens or such.

Indeed, Paul repeatedly refers, not simply to Jesus’ death, but specifically to his crucifixion, which in Paul’s time was a particular form of execution conducted by Roman authorities against particular types of individuals found guilty of particular crimes. Crucifixion requires a historical figure, executed by historical authorities. Jesus’ historical death by crucifixion was crucial and central to Paul’s religious life and thought.[xviii] To cite one text from many, “We preach Christ crucified” (1 Cor. 1:23).

Or consider Paul’s explicit reference to Jesus as “born of a woman, born under the Law” (Galatians 4:4). Paul here clearly declares Jesus to have been born, as mortals are, from a mother, and, further, born of a Jewish mother “under the Law.”[xix] Birth from a mother, and death and burial—surely the two clearest indicators of mortal existence! Moreover, Paul considered Jesus to be specifically of Davidic descent (Romans 1:3), and likewise knew that Jesus’ activities were directed to his own Jewish people (Romans 15:8).[xx]

Paul refers to Jesus’ physical brothers (1 Corinthians 9:5) and to Jesus’ brother James in particular (Galatians 1:19). Contrary to mythicist advocates, the expression “brothers of the Lord” is never used for Jesus-followers in general, but in each case rather clearly designates a specific subset of individuals identified by their family relationship to Jesus.[xxi] Note particularly that in Paul’s uses, the expression “brothers of the Lord” distinguishes these individuals from other apostles and leading figures. The mythicist claim about the expression is a rather desperate stratagem.

Paul knows of a body of teachings ascribed to Jesus, and uses them on several occasions, as in 1 Corinthians 7:10-11, where he both invokes a specific teaching discouraging divorce, and also acknowledges that he has no saying of Jesus at other points and so has to give his own advice (e.g., 7:12). Rather clearly, the source of the sayings of Jesus was not some ready-to-hand revelation that could be generated, but instead a body of tradition that Paul had inherited. Certainly, Paul refers to his many visions and revelations (2 Corinthians 12:1), and even recounts one at length (vv. 2-10). But he also refers to a finite body of teachings of “the Lord” that derived from the earthly Jesus and were passed to him.

It would be tedious to prolong the matter. In Paul’s undisputed letters, written decades earlier than the Gospels we have clear evidence that the “Jesus” referred to is a historical figure who lived among fellow Jews in Roman Judea/Palestine, and was crucified by the Roman authority. There is no shift from a purely “celestial being” in Paul’s letters to a fictionalized historical figure in the Gospels. For both Paul and the Gospels, Jesus is both a historical figure and (now) the “celestial” figure exalted to God’s “right hand” in heaven. Whatever you make of him, the Jesus in all these texts is never less than a historical mortal (although in the light of the experiences of the risen Jesus he became much more).

We have examined each of Carrier’s three claims and found each of them readily falsified. It’s “three strikes you’re out” time. Game over.

There are much better reasons offered by people for finding Christian faith (or any kind of belief in God) too much of a stretch. The attempts to deny Jesus’ historical existence are, for anyone acquainted with the relevant evidence, blatantly silly. So, let those who want to argue for or against Christian faith do so on more serious grounds, and let those of us who do historical investigation of Jesus and Christian Origins practice our craft without having to deal with the strategems-masquerading-as-history represented by the mythical Jesus advocates.

[i] The validity of the claim that God resurrected Jesus and exalted him is beyond historical investigation to determine. But the early eruption of these claims is a historical datum not typically disputed.

[ii] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We May Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield Academic Press, 2014).

[iii] From a posting by Carrier: http://www.bibleinterp.com/articles/2014/08/car388028.shtml#sdfootnote1sym.

[iv] See, e.g., Saul M. Olyan, A Thousand Thousands Served Him: Exegesis and the Naming of Angels in Ancient Judaism (TSAJ 36; Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr, 1993); and Michael Mach, Entwicklungsstadien des jüdischen Engelglaubens in vorrabinischer Zeit (TSAJ 34; Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr, 1992); Maxwell J. Davidson, Angels At Qumran: A Comparative Study of 1 Enoch 1-36, 72-108 and Sectarian Writings From Qumran (JSPSup 11; Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1992); L. W. Hurtado, “Monotheism, Principal Angels, and the Background of Christology,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Dead Sea Scrolls, ed. Timothy H. Lim and John J. Collins (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 546-64; Paul J. Kobelski, Melchizedek and Melchiresa (CBQMS 10; Washington: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1981). Carrier refers to Philo, but Philo never mentions an archangel named “Jesus”. Philo makes a theological/conceptual distinction between the ineffable God and God revealed, and calls the latter God’s “Logos,” but he makes it clear that they don’t really comprise two separate beings.

[v] Tal Ilan, Lexicon of Jewish Names in Late Antiquity, Part 1: Palestine 300 BCE – 200 CE, TSAJ 91 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2002), gives a list of male and female Jewish names in second-temple evidence. Note also Margaret H. Williams, “Palestinian Jewish Personal Names in Acts,” in The Book of Acts in Its First Century Setting, Volume 4: The Book of Acts in Its Palestinian Setting, ed. Richard Bauckham (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995), 79-113, who notes numerous instances of the name for figures referred to by Josephus, on ossuaries (sometimes the Aramaic form, Yeshua, sometimes the Greek form, Iesous). The name “Jesus” is an anglicized form of the Greek, Iesous, which in turn is a Graecized form of the Hebrew name, Yehoshua (“Joshua”), its Aramaic/shortened form, Yeshua. There are about ten individuals with the name in the Hebrew OT (usually translated “Joshua”), and others with the name “Jesus” in the Greek NT (Matt. 27:16; Col. 4:11; Luke 3:29). And note also the Jesus, the grandfather of the author of Ecclesiasticus (or the Wisdom of Jesus son of Sirach).

[vi] For a survey of the various types of “chief agent” figures in second-temple Jewish tradition, including high angels, see my book, One God, One Lord: Early Christian Devotion and Ancient Jewish Monotheism (3rd ed.; London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015; original edition, 1988). None of these figures, however, gives a full analogy for the programmatic place of Jesus in the devotional practices of earliest Christian circles.

[vii] See, e.g., Mary Beard, John North and Simon Price, Religions of Rome (2 vols; Cambridge University Press, 1998); Robert Turcan, The Cults of the Roman Empire, trans. Antonia Nevill (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996). On the many “mystery cults,” see now Jan N. Bremmer, Initiation into the Mysteries of the Ancient World (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014).

[viii] Carrier seems to misconstrue the classic Euhemerist theory, which postulated that the various gods derive from ancient human heroes who across time developed into gods, not the opposite.

[ix] Among many studies of Mark’s presentation of Jesus, e.g., Elizabeth Struthers Malbon, Mark’s Jesus: Characterization as Narrative Christology (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2009).

[x] Perhaps the authors of the Gospels were concerned to re-assert the importance of the historical ministry of Jesus as indispensable. See Larry W. Hurtado, “Resurrection-Faith and the ‘Historical’ Jesus,” Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus 11.1 (2013): 35-52; and my discussion of the Gospels as literary expressions of Jesus-devotion in my book, Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 259-347.

[xi] E.g., Larry W. Hurtado, “Gospel (Genre),” in Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels, ed. J. B. Green, S McKnight and I. H. Marshall (Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Press, 1992), 276-82; David E. Aune, The New Testament in Its Literary Environment (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1987); and more fully on the Gospels, R. A. Burridge, What Are the Gospels? A Comparison with Graeco-Roman Biography, SNTSMS 70 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

[xii] Larry W. Hurtado, “The Gospel of Mark: Evolutionary or Revolutionary Document?” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 40 (1990): 15-32.

[xiii] These are Romans, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, and Philemon. The other Pauline letters in the NT are judged by most scholars to be either posthumously produced in Paul’s name (especially Ephesians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus), or are disputed as to authorship (especially Colossians and 2 Thessalonians).

[xiv] Matthew V. Novenson, Christ Among the Messiahs: Christ Language in Paul and Messiah Language in Ancient Judaism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), shows persuasively that in Paul’s usage “Christ” (Greek: Christos) retained the sense of “Messiah,” correcting an earlier scholarly view that the term had become an empty name for Jesus.

[xv] See my discussion of Pauline Christianity in my book, Lord Jesus Christ, 79-153; and my more concise treatment, L. W. Hurtado, “Paul’s Christology,” in The Cambridge Companion to St. Paul, ed. James D. G. Dunn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 185-98.

[xvi] Larry W. Hurtado, “Pre-Existence,” in Dictionary of Paul and His Letters, ed. G. F. Hawthorne and R. P. Martin (Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Press, 1993), 743-46.

[xvii] Charles A. Gieschen, Angelomorphic Christology: Antecedents and Early Evidence, Arbeiten zur Geschichte des Antiken Judentums und des Urchristentums, no. 42 (Leiden: Brill, 1998), argued that early Christians appropriated “angelomorphic” language and motifs in articulating the heavenly status and glory of the risen Jesus, but, he emphasizes, this did not amount to treating Jesus as an angelic being. Cf. Bart D. Ehrman, How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2014), e.g., 250-51, who gives a confused representation of matters.

[xviii] The mythicist attempt to make Paul’s reference to Jesus’ crucifixion by “the rulers of this age” (1 Cor 2:7-8) into some kind of heavenly event is bizarre. All else in Paul’s letters confirms that he knew Jesus’ crucifixion as an earthly, historical event, and the “rulers” here are likely those under whose authority it was carried out. If, however, “the rulers” (archontes tou aiwnos toutou) designate spiritual beings, the statement would reflect the view (well attested in Jewish and early Christian sources) that spiritual forces are behind the earthly rulers, acting through them. But there is no basis for making the event something that took place solely in some spiritual realm apart from earthly history.

[xix] Contra Carrier’s ill-informed claim, the Greek verb ginomai is frequently used in various Christian and non-Christian texts to mean “born.” There is nothing in Paul’s statement to justify Carrier’s strange claim that it portrays something other than a normal birth. Any lexicon will confirm this: e.g., The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek, ed. Franco Montonari (Leiden: Brill, 2016), s.v. γινομαι.

[xx] As a devout believer in the one God, in Paul’s view, Jesus’ death was for redemptive purposes, and Paul could therefore also refer to God having sent Jesus for redemptive death, or having “handed him over” for redemptive death, as in Romans 3:21-26; 4:24-25.

[xxi] The term “brothers” (of fellow Christians) is a frequent intra-group designation in the NT, but “brothers of the Lord” is not. For a thorough study of this and other terms, see now Paul Trebilco, Self-Designations and Group Identity in the New Testament (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).