The annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, this year in Chicago, transpired under surprisingly sunny skies and mild and clement weather. Certainly a good time was had by many. As for me I gave a lecture at the Bible Fest sponsored by the Biblical Archaeology Society on 1 Corinthians 11 and women’s hair and headcoverings entitled ‘A Veiled Threat’, and also the keynote address at the IBR (Institute of Biblical Research), which got a spirited rebuttal from Professor Stan Porter of McMaster.

Below is the lecture itself (without of the footnotes), which I had only 40 minutes to deliver, so I simply gave highlights. See what you think.

‘ALMOST THOU PERSUADEST ME….’ THE IMPORTANCE OF GRECO-ROMAN RHETORIC FOR THE UNDERSTANDING OF THE TEXT AND CONTEXT OF THE NT

“It is time to bring the rhetoric of the apostle and rhetoric of his ancient interpreters together.”— Margaret Mitchell

Some adults have experience with texts but others do not. To the latter a document is just parchment and ink, not a means by which the living voice of an absent friend is known.— John Chrysostom Homily on 1 Cor. 7.2

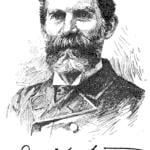

Ben Witherington, III

I was marking a doctoral thesis for the Australian College of Theology recently with the title ‘Preaching the New Testament as Rhetoric’. It was a very fine thesis in many ways, the essence of which was that the text of the NT should be preached with full awareness of what this or that portion of a discourse was originally intended to do rhetorically. Thesis statements of discourses should be preached accordingly, arguments should be preached accordingly, perorations should be preached accordingly, complex rhetorical devices like impersonation in Romans 7 should be identified, explained, and then exposited on, and so on. Ethos, Logos, and Pathos in a discourse must be recognized and dealt with in light of its emotive intent and content. You get the picture.

In other words, this doctoral candidate realized it’s not enough to just recognize and have a nodding acquaintance with what I call the micro-rhetoric of the NT— rhetorical questions, the use of rhetorical hyperbole and the like. Not enough to just recognize the elements of style and literary figures in the NT. You need to know the species of rhetoric used, you need to know where in the argument you are with a particular rhetorical unit, you need to know whether this is an argument for something, or, as in the case of Rom. 9-11 or 2 Cor. 10-13 an argument against something. In other words, not merely for the understanding of the NT, but also for the proper preaching of the NT, you need to be conversant with Greco-Roman rhetoric, the sort you find in lots of places in the NT— particularly in Paul, Luke-Acts, Hebrews, 1 Peter, Jude and I could go on.

“But wait….” I hear a potential debater of this age say, wanting to engage in a rhetorical diatribe with me, “Surely, this is a bridge too far! Small rhetorical devices, fair enough. Recognizing them doesn’t much change the meaning of the text or affect the way I read it. Surely, it’s a bridge too far to argue that Paul or the author of Hebrews or Luke or other early Christians knew and used Greco-Roman rhetoric in detail. Weren’t the first followers of Jesus simple peasants, or fishermen with the smell of bait on their hands? Don’t epistolary conventions adequately explain the architectonic structures we find in, say, 1 Corinthians? Isn’t it over-egging the pudding (as the British would say), to claim that Greco-Roman rhetoric is an essential key to understanding the New Testament? Surely Witherington, ‘thou protesteth too much!’ After all, isn’t this just one more new faddish way to read the NT, and as we all know— “methodological fads come, and methodological fads go.”

Yes, I could compose a rather fulsome diatribe made up of the objections I have heard in the last twenty years to a detailed rhetorical or socio-rhetorical reading of the NT ranging from the sublime to the ridiculous. Time will not allow me to do so now, but we all know who have made and continue to make such arguments, and some of them are at this very IBR session today. If you want to see a representative summary of such arguments see the recent article by Stan Porter and Bryan Dyer in the most recent issue of JETS, though it focuses purely on the Pauline material.

My task this evening is to present to you with some reasons why, if this is indeed your view, you really ought to reconsider. The first portion of the lecture will be devoted to a ground-clearing exercise, in the second part of the lecture you may expect a positive presentation— in other words, preliminary considerations and ‘refutatio’ first, followed by ‘probatio’ second. Finally, as time allows, I will show in some more detail that even very complex rhetorical techniques are in play in the NT.

OBJECTION TO NEW FANGLED METHODS

Nobody likes to be told that the methods one has employed to study the Bible, low these many years, are inadequate, out-moded, short-sighted, or involve major oversights. Of course not. The older you get, the more ‘set in your ways’ you become. So when, someone comes along and says ‘you need to read Aristotle and Quintilian to understand the NT’ understandably there is going to be some push back.

One of the forms the objection takes is the time-honored rebuttal— “This is a new fangled method of interpretation. It does not have a proper long scholarly pedigree. My teachers didn’t use it. Their teachers didn’t use. I can safely ignore it and dismiss it.” If you have ever thought these thoughts or said these things about Greco-Roman rhetoric and the NT, perhaps it’s time for a major rethink and attitude adjustment. Actually this so-called new fangled method is quite old fashioned, as we shall see.

May I just quietly suggest here at the outset that, Part of the problem is the deficiencies of our own modern educations, not the deficiencies of Paul’s or Luke’s education. Most of us in this room, in all likelihood, have not had a classical education in addition to a Biblical one. The longer time has gone, the more I realized I was in a distinct minority among Biblical scholars in having done classics in junior high school, and high school and college, and then through a singular providence of God just happened to be attending the university where George Kennedy, among others, showed up, back at the dawn of time when the earth was still cooling— by which I mean at the beginning of the 1970s when I went to Carolina.

In regard to analyzing the NT on the basis of Greco-Roman rhetoric, let me be clear that this was already the practice of many of the Greek Church Fathers (e.g. Origen, Gregory, Basil and Chrysostom), the most able of which was John Chrysostom. As Margaret Mitchell has shown in great detail in her wonderful book The Heavenly Trumpet Chrysostom knew, and demonstrated over and over again that Paul’s letters were more profound rhetorical discourses than they were letters, and he preached them accordingly and very effectively, using rhetoric to do so. More recently she has shown at length how Gregory of Nyssa and others also interpreted Paul and other parts of the NT rhetorically. So much were early Greek speaking Christians familiar with and using rhetoric to teach the NT that Julian the Apostate had to ban Christians from teaching Greek grammar and rhetoric in the private or even public schools in A.D. 361-63 because he was afraid they would show their students the merits of the rhetoric in the NT! Margaret Mitchell in her most recent monograph stresses “the consistent usage of rhetorical terminology and techniques in patristic exegesis—by Alexandrines and Antiochians alike (and Carthaginians and Cappadocians and others)—has been abundantly documented”. Exactly right. Some NT scholars just haven’t kept up with the increasingly voluminous evidence on this score from classicists and patristics scholars.

In short, there is absolutely nothing ‘nouveau’ about the notion that the NT ought to be analyzed on the basis of Greco-Roman rhetoric. It is a time-honored practice that has produced remarkably helpful results for well over a thousand years. It pre-dates the historical critical method, including modern epistolary analysis, by over a thousand years. In short, whether you fancy form, source, textual, redactional, epistolary, historical, archaeological, reader-response, narratival, higher or lower criticism or some other recent –ism, all these methods are the new kids on the block. Not so historical rhetorical analysis of the NT.

It is an odd thing, that I personally have received the strongest push back against analyzing the NT in a rhetorical way by staunch defenders of Augustine and Luther and Calvin. I say odd because: 1) Augustine’s De Doctrina Christiana set the pattern for studying the NT in terms of Greco-Roman rhetoric for the Western Church, and he was followed in this by 2) Calvin and Luther, and 3) then Melanchthon produced full scale commentaries on the NT analyzing it in terms of its Greco-Roman rhetoric, and even wrote a handbook on classical rhetoric using the NT to illustrate said usage! In short, even in the Protestant tradition, and even in the Reformed and Lutheran traditions there is a very long precedent for analyzing the NT this way. And this brings us to another point raised in the aforementioned article by Porter and Dyer.

They lament that if I’m right that we need to read the NT in detail in light of Greco-Roman rhetoric, then we’ve been misreading the NT for a long period of time. Actually, this is a yes, and no proposition. Yes, most modern readers of the NT do not read the NT the way the Greek Fathers did, which is to say, in a rhetorically adept and informed way. I’m suggesting we should do so, at least as one important way of fruitfully reading the text.

What I am certainly not saying is that there is little that is helpful and little to learn from epistolary analysis of the NT or various other ways we analyze the NT based on the historical critical method. Me genoito!! What I am saying to those who simply plow any of those familiar historical critical furrows is, that you are simply missing an enormous amount of insights into the NT text, indeed essential clues to the meaning of various texts, by ignoring or dismissing historical rhetorical analysis of the NT. And when you ignore or overlook something that is major or essential, yes it leads to skewed interpretations some of the time. It leads to putting the emphasis on the wrong syllable, so to speak. So, it’s not a case of ‘I’m right, and Porter and Dyer are totally wrong’. I’m saying, that however helpful their methodology is, they are missing out on some essential insights into the NT text and its meanings, and who doesn’t want to more fully and better understand the NT text?

IT’S NOT HISTORICALLY PLAUSIBLE

Perhaps however, your real issue with analyzing the NT on the basis of Greco-Roman rhetoric comes from your analysis of the historical Sitz im Leben of the earliest Christians. The argument goes something like this. ‘Not many of the earliest Christians were among the social elites of society. This means not many of them got what one might call a higher education. After all, none of the writers of the NT go around wearing Tarsus U. T-shirts and bragging about their educational pedigree and prowess. Since they did not have a ‘higher’ education, they would not have known the full taxonomy of Greco-Roman rhetoric and would not have used it anyway, as they were mostly Jews, drawing on the OT for their polemics and arguments’. There are all sorts of historical problems with this analysis of the social situation of early Christians, and I will have to be satisfied with listing some of the more salient ones:

1) From a historical point of view, Hellenization, complete with language immersion and Greek culture had influenced the entire Biblical world, including Galilee and the Roman province of Judaea, for many centuries by the time the very first NT document was written. Martin Hengel demonstrated this a long time ago, and it does not need to be rehearsed here. He even demonstrated that there were schools of Greek rhetoric in Jerusalem in Paul’s day! There is a good reason the whole NT is written in Greek. It was the lingua franca of the Roman Empire, the language that most everyone knew, and knew they needed to know, just as today English is the overwhelmingly dominant language of the Internet.

Language is the gateway into a culture. It is the doorway into an education.

In the NT we have 27 books all of which were originally written in Greek, and all of which reflect not merely Greek diction, but Greek ideas, Greek culture, Greek influence of various sorts, including the influence of Greco-Roman rhetoric. This in no way is meant to deny the obvious Jewish and OT influences as well. To use a trope— the hands are the hands of Virgil, but the voice is the voice of Jacob. Jacob, however, has learned some Greek ways along the way, though of course it’s ‘not all Greek to him’.

2) The notion that early Christianity was led by a bunch of illiterate Jewish peasants is an historical myth. It may seem a pleasant fiction to Dom Crossan and others, but it is a myth. The statement in Acts 4.13 is not claiming that Peter and John were ‘illiterate’. The Greek says they were agrammatoi kai idiotai, which does not mean they were illiterate idiots. It means that they had not studied with the scribes in Jerusalem, nor had an education there. It means they were not ‘initiated’ into the learned ways of those in the Sanhedrin, and thus were not ‘insiders’. Whatever education they had gotten, it had been gotten in Galilee. This does not make them illiterate peasants. What we see here is the typical snobbery of the Jerusalem elites.

I take seriously however the fact that Papias tells us that Peter preferred to teach in Aramaic, and that Mark had to render some of his teachings into Greek in his Gospel. Peter needed help to produce good persuasive Greek discourse in writing. I believe he got it from the likes of Silvanus and Mark. In the former case the help of Silvanus must have been considerable, as 1 Peter reflects Greco-Roman rhetoric in detail. As Papias goes on to add, even Mark felt a need to form his pithy narratives in the form of rhetorical chreia so they would be persuasive.

3) In regard to ancient education in Greek, several points need to be made. Firstly, there were schools and teachers of rhetoric all over the Empire, including some of the more famous rhetoricians right in and around Galilee. Josephus the historian, Theodorus the rhetorician, Meleager the poet, and Philodemus the philosopher all hailed from Galilee and got their training in the Holy Land. Both the ‘grammateus’ and the ‘rhetor’ were teachers and both taught rhetoric and taught rhetorically.

No one who has spent any considerable period of time in Sepphoris and seen the mixture of Jewish piety with Greco-Roman art, architecture, astrological practices, educational practices and the like can doubt that even Galilee was a mixed-language, mixed-cultural milieu where Greek was regularly used. The Greek inscriptions side by side with Hebrew and Aramaic ones in places like Capernaum, Migdal, and Chorazim are clear testimony to the mixed language, mixed cultural nature of the Galilee. If we believe that Jesus actually had private conversations with centurions or even with Pilate, the language that would have been used was surely Greek, though of course Jesus’ and Peter’s dominant spoken language was Aramaic.

My point is this—no significant place in the Roman Empire had escaped the influence of Hellenization, Greek culture and rhetoric, and this includes Galilee and Samaria. Take for example the case of Justin Martyr born around or a bit before 100 A.D. at Flavia Neapolis (ancient Shechem, modern Nablus) in Samaria of Greek parents. He was brought up with a good education in rhetoric, poetry, and history. This he got in Samaria and Galilee. Martin Hengel puts the matter this way: “Judaea, Samaria, and Galilee were bilingual (or better trilingual) areas. While Aramaic was the vernacular of ordinary people, and Hebrew the sacred language of religious worship and of scribal discussion, Greek had largely been established as the linguistic medium for trade, commerce and administration.” It was also the language for those wanting to ‘get ahead’ in life through close association with the elites, such as the Herods, or even the Temple elites in Jerusalem.

4) Rhetorical education began at what we would call the primary school level. It is already present in the progymnasmata, as even a cursory reading of Kennedy on the Progymnasmata (SBL 2003) or Ron Hock and Ed O’ Neil’s fine book The Chreia and Ancient Rhetoric (SBL 2002) will show. When Theon in the first century A.D. began to teach letter writing to his students who were studying the progymnasmata he told them— ‘compose these fictional letters as a rhetorical exercise and in the form of what is called prosopopoiia’.

Furthermore, classics scholars have shown that even brief letters by a Pliny, or a Seneca reflect the structure— proposition, an objection, an argument, and a peroratio, (see Pliny’s Ep. 1.11 and 2.6 and the 13th-15th Epistula morales of Seneca). But long before them, we have the clear example of Demosthenes’ First Epistle that is arranged as a deliberative discourse would be, as J.A. Goldstein long ago demonstrated. My own colleague Fred Long has more recently provided us with a plethora of examples of forensic speeches in epistolary form. If we are talking about later Christian letters Basil’s consolatory rhetoric in letters (Epistle 5, Epistle 6) consists of proem, encomium, and some exhortation with concluding prayers. Here the article of Porter and Dyer overlooks much of the actual historical evidence and precedents of letters in rhetorical form from before, during, and after NT times. It would not take years of study to become adept at rhetorical composition using an epistolary framework. There are clear precedents from during and before the NT era.

We will say more about prosopopoiia at the end of this lecture, if there is time, when we examine how Paul uses it in Romans 7, but we have already noted how this rhetorical technique is even introduced at the beginning of rhetorical training. In any case, you didn’t need to have a higher education to know basic Greco-Roman rhetoric. You could compose rhetorically shaped letters even after an elementary education. And you didn’t necessarily need to have a formal rhetorical education at all to recognize and appreciate the art. Why not?

5) As Duane Litfin rightly said a good while ago , the Roman Empire was a rhetoric-saturated realm. It was in the education, in public speeches, in the inscriptions, in the Imperial propaganda, and we could go on. Litfin goes on to rightly stress that most of the Greek-speaking persons in the Empire were either producers or avid consumers of rhetoric. There were even rhetoric and poetry contests at the games throughout the Empire. It was a spectator sport in the first century A.D.

If early Christianity really was an evangelistic religion wanting to persuade a Greek-speaking world about the odd notion that a crucified manual worker from Nazareth rose from the dead and was King of kings and Lord of lords, this was going to take some serious ‘persuasion’ and the chief tool in the arsenal of all well known persuaders, orators, rhetoricians in the Greco-Roman world was rhetoric. This was especially so if, as seems likely, the Christian evangelists like Paul had an urban strategy, seeking to begin evangelism in the major cities of the Empire, which is to say the very places where education and rhetoric were most in evidence in the Empire.

6) As Edwin Judge has demonstrated over and over again, large portions of early Christianity, particularly the more Gentile portions were led by several rather remarkably gifted and indeed well-educated persons— persons like Paul, Apollos, Luke, and others. The culture was largely an oral culture, not a culture of texts, and since preaching was going to be the main modus operandi for the spread of the Good News, it needed to be Greek preaching that would persuade various target audiences. The obvious tool was Greco-Roman rhetoric.

There is a reason why Luke in Acts says absolutely nothing about Paul being a letter writer. This is because it was an entirely secondary and surrogate means of communicating the Gospel in the first century, even when it comes to Paul. Indeed, letters were used to convey the messages Paul would have spoken directly to his converts had he been present. They are simply part of a total communication effort that took ‘the living voice’ as primary, and texts as secondary. ‘ [read the intro quote from Chrysostom here]. It is not an accident that the phrase ‘Word of God’ in the NT never once refers to a text— rather it refers to the oral proclamation of the Gospel in Acts and in Paul (see e.g. 1 Thess. 2.13) and in Hebrews, and to a living person (Jesus) in John and Revelation.

7) What about the attempt to point to the book trade as evidence that texts were widespread and there was a considerable culture of texts in the NT world? Porter and Dyer ignore the evidence amassed by William Johnson and other classics scholars who have studied the ancient book trade at length. This was a trade supported by and catering to the Roman elites. It was definitely not a trade that supplied any significant number of ordinary people with all sorts of texts such as the lengthy documents we find in the NT. To use the book trade as an argument for widespread texts or texts being in the possession of a large number of ancient persons, or even as an argument against the largely oral character of the Biblical world, is a dog that just won’t hunt if you actually examine the origins of the book trade in the first century A.D., its audience and its character.

The attempt to minimize the cost of preparing ancient manuscripts of the sort of length we find often in the NT does not work either. Galen is clear enough that only a wealthy person could afford to collect or have real books (not brief business contracts or telegraphic missives). He says to a wealthy friend “I see that you cannot bring yourself to spend your wealth…on the purchase and preparation of books, nor on the training of scribes, whether in shorthand ability or in fine and accurate writing, nor even on lectors who read well…” (de. An. Aff. Dign. Et Cur. 5.48). Notice the taxonomy here— it takes wealth to afford to produce books, to hire scribes, and perhaps most importantly to hire readers. Why would you need a lector if you are functionally literate? Because in most all settings, including in ancient libraries, people read out loud as Johnson demonstrates and a lector had the skills to do it in a rhetorically effective manner, whether in a church meeting or as the after dinner reader or rhetor at a symposium.

William Johnson’s book Readers and Reading Culture in the High Roman Empire, should be required reading for all students of the NT letters. What it shows is that the book trade was just beginning to grow in the first century A.D. and overwhelmingly it served the elites and wealthy of the Empire, not ordinary persons, which is to say, it did not serve many in the early Christian audiences. They were served by hearing NT documents, not primarily by reading them as mute texts.

Notice the distinction in Rev. 1.1-4 between the person who reads out the document (a ‘reader’ in the singular) and those who hear it. The vast majority of texts in antiquity, especially the longer ones written in ‘scriptio continua’ were and had to be read out loud to be made sense of as they lacked separation of words, sentences, paragraphs, and yea verily they had no chapters and verses. These were oral texts. The way you decipher them is by reading them out loud. [display here texts from powerpoint] Consider for example the report Justin Martyr gives us about an early Christian meeting in his day—

On the day called Sunday, all who lived in the cities or in the country

gather together, to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles

or the writings of the prophets are read aloud, as long as time permits,

then when the reader has ceased, the President verbally instructs

and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. (First Apology 65)

Notice the clear distinctions made in this report— there is a reader, a lector, who reads the memoirs of the apostles out loud, there are those from the cities or countryside who gather together to hear him do so, and then there is a different person ‘the presiding official’ who exhorts after the reading. This of course is just like the procedure in the synagogue only in this case the apostolic writings, are treated just like the OT prophets— as a sacred text to be read aloud to the community.

8) Sometimes there has also been push-back against the Greco-Roman rhetorical analysis of the NT on the basis of 1 Corinthians 1-2 to this effect— ‘Paul says he is not going to use lofty words or wisdom but the foolishness of preaching to convict, convince, and convert persons in Corinth and elsewhere. Ergo, he must be renouncing the use of rhetoric’. There are now of course detailed studies of this very text that demonstrate beyond reasonable doubt that Paul is not renouncing Greco-Roman rhetoric. What he is renouncing is sophistry, sophistic rhetoric ‘full of sound and fury but signifying nothing’. Read Bruce Winter’s detailed study Are Paul and Philo among the Sophists on the first batch of sophists and their effect on rhetoric in the first century A.D., or for that matter read my Conflict and Community in Corinth. Margaret Mitchell puts it this way: “[O]ur wordsmith would recast his initial visit using the customary rhetor’s topos: no real wizard with words, indeed (like Demosthenes) trembling in his sandals and out of his natural element…And yet, despite the anti-rhetorical rhetoric, it was inescapably a verbal proclamation, a ‘logos’ and a ‘kerygma’”. In short, Paul is using rhetoric to refute the notion that he was a purveyor of mere verbal eloquence. That is all.

Peter Lampe puts it this way, in discussing this oft-misunderstood passage—“Thus Paul does not rebuff any rhetorical art in general, but the one that specifically tries to invoke pistis in Christ by means of bedazzling and seductive rhetoric.” This is precisely what Paul himself says in 1 Thess. 2.5 using the same terms to critique sophistry as was used earlier by the followers of Plato and Aristotle who themselves used substantive rhetoric to make their points (see Plato Gorgias 463B). The critique of a specific sort of superficial verbal pyro-techniques is intended to clear the way for accepting and understanding more serious rhetoric. It is not an example of rejecting rhetoric altogether (see also Seneca Ep. 45.5;49.5-6;111).

9) Perhaps the most frequent objection I hear to the notion that the NT, and particularly the letters, should be read in light of Greco-Roman rhetoric is that “these documents are letters and conform to the pre-existing epistolary conventions”. Most of us received training to that effect along the way in our Biblical education. But when one actually examines what was the historical educational situation in the Empire in and even before the first century A.D. it becomes clear that epistolary analysis cannot be the sole or even the primary tool for analyzing these documents for a whole variety of reasons. Let me be clear. Yes I think epistolary analysis of the letters of the NT is important. No, it’s not as important as rhetorical analysis of these documents, if the goal is to understand the character and form of these documents between their opening and closing epistolary elements. We should have heeded the blunt remarks of Cicero on this front who stresses that a letter [of the sort we are discussing] is in effect “a speech in written medium” (ad Atticum 8.14.1; cf. Pseudo-Demetrius De elocutione 223).

Note that I do not say epistolary analysis is inappropriate or irrelevant. I am simply saying that: 1) it should not be the dominant much less the sole literary way we analyze these documents; and 2) epistolary conventions and forms are not what shapes the vast majority of these documents which are rightly called letters. In other words, even the letters in the NT are more shaped by rhetorical than by epistolary conventions. In any case, we must bear in mind that pseudo-Libanius’ epistolary handbook dates to the 4th century A.D. and as for pseudo-Demetrius, it may come from the latter half of the first century, but we have no evidence it was widely used by tutors and schools in that era, in contrast to the teaching of rhetoric.

10) As an aside, I must mention that some of the documents we have identified as NT letters do not appear to be letters at all. For example 1 John is a rhetorical sermon or homily. It has no epistolary features at all—even at the beginning or end of the document. Hebrews is a sermon, which has an epistolary conclusion because it is sent from a distance. But if we ask what is really shaping this document’s structure, it is not epistolary conventions or structures. I could go on and on, but this is enough to show that the usual objections to finding rhetoric in the NT in detail do not stand up to close historical scrutiny. They just don’t.

11) By the same token the actual NT evidence does not support mainly treating these NT letters as like the private communications of Cicero to Atticus. To take but one example, Philemon is a deeply personal discourse, but it is in no way private—written to Philemon, his family, and ‘the church which meets in his house’. What we have in the NT, almost without exception are communications composed for groups of people meant to be read out loud to groups of people (the Pastorals and 3 John being possible exceptions). They are not documents meant for private individuals to quietly read at their leisure, and as such they are not much like the vast majority of ancient letters on papyri we know about.

Chris Forbes rightly concludes “Paul’s congregational letters…are a remarkably isolated phenomenon in their cultural context. This is true both at a purely literary level and in terms of the social context that generated them….Paul’s letters were not written to be read, but to be performed. As such they function as speeches, as rhetoric, every bit as much as they function as conventional letters.” Recently Craig Keener sent me the following references:

Cf. Epict. Diatr. 1.1: starts “Arrian to Lucius Gellius,” and then introduces the discourses.

–Cf. the history, 2 Macc 1:1-6—epistolary prescript for a historical work. 2 Macabees 1:1-2:32, prologue; esp 1:1—specifically epistolary.

–Aune, Literary Environment, p. 240: Rev is the only apocalypse “framed by epistolary conventions, for the pseudonymity of other apocalypses would necessitate a fictional receiver as well as sender.”

–Cf. Cicero Brutus 2.11 (LCL pp. 24f): Cicero tells Atticus that his presence “lightens my care, and when absent too you afforded me great solace. For your letters first restored my spirits” (LCL p. 25 note c—these “letters,” litteris, are really “treatises dedicated to Cicero”).

12) Here it may be useful to point out one final red herring. Sometimes you will hear the opponents of rhetorical analysis of the NT, particularly the letters, say something like this: “If you read the various scholarly rhetorical analyses of these documents when it comes to species or invention or arrangement, there is no consensus of opinion even on a document as short as Philippians. Some say it’s epideictic, some say its deliberative, and the particulars of the rhetorical arguments or units are analyzed variously.” While there is some truth to this (though over time there has been more and more of a consensus about Philippians or Hebrews or Galatians), I would simply point out that there is no consensus about epistolary analysis of these documents either!

Where the prescript begins, what the function of the greeting or the body middle is, where the postscript starts, what the function of the signature is— frankly there are as many opinions on these things among scholars on any given letter, as there are about the rhetoric of these same documents. In short, lack of clear scholarly consensus about the arrangement of the rhetoric or its species in a given case is no argument against rhetorical analysis of the document any more than a lack of consensus about the epistolary analysis is. It has been well said that if you put five scholars in a room six opinions emerge on any given subject. Yea verily.

PROBATIO— THE CASE FOR RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE NT

A few basic reminders about ancient education are in order at this juncture. There are now numerous studies about education in the Biblical world that make clear beyond reasonable doubt that rhetoric was an essential part of education at all three levels, all over the Empire. There were no schools of letter writing in Paul’s day, but there were both schools of rhetoric and rhetoric in more general schools. When one learned from even an individual tutor or a grammateus, rhetoric was part of the basic education, particularly for males who would have to speak in various public settings and forums and needed to know how to do it effectively. Rhetoric had been a part of education from the time of Aristotle, whereas the writing of what came to be called letter essays, letters with extended profound philosophical or theological content in Greek or Latin was mostly a much more recent practice in the Roman world, dating to the time of Cicero.

It is true enough that by the time we get past the NT era into the second and third and fourth centuries we begin to have letter-writing handbooks by pseudo-Libanius and others. Notice however that letter writing is not yet a staple, broadly-used, part of any education in the Empire during the time when these NT documents were being written. It was a discipline in the process of being developed during the NT age. The later detailed taxonomy of pseudo—Libanius in which he parses out numerous different types of letters (ambassadorial, friendly etc.) does not seem to have yet existed in the First Century A.D. Therefore, use of such detailed epistolary taxonomies runs the danger of clear anachronism. Reading into the text of later categories.

The chief help that knowing about ancient letter writing gives us in analyzing the NT is in discussing the epistolary prescripts and greetings and postscripts of the NT letters. That is all. So far as I can see, there was no epistolary convention to offer a thanksgiving or blessing prayer at the beginning of an ancient letter. I have read a lot of ancient letters and they do occasionally include a health wish at some juncture, but that is not a thanksgiving or blessing prayer or prayer report either in length or in character. And as for the amazing range of arguments that show up in the Pauline corpus and elsewhere in NT letters after opening pleasantries, epistolary conventions help us with them hardly at all. In other words, we get little or no help in analyzing the bulk of the material in NT letters on the basis of ancient epistolary forms and practices. It is striking to me that almost all the typical formulae pointed out in NT letters by various NT scholars as stereotypical epistolary ways to introduce a new topic (e.g. ‘I want you to know…’ or ‘I appeal to you…’) are in fact discussed by Quintilian as classic ways to introduce rhetorical topoi in discourses (see Inst. 4.2.22)! I would simply remind you that there was no ancient epistolary category called ‘the body middle’ introduced by such formulae. There just wasn’t.

One of the things we have to do from time to time is unlearn some things, in light of further evidence. We need to unlearn some of things we were told was true about NT letters in form critical studies and manuals and books and monographs. We need to unlearn them because the NT writers were mostly not writing according to those sorts of later conventions. We need to unlearn them because they are anachronistic and not all that helpful in studying the NT in its original historical contexts, including its rhetorical context.

Re-reading some of the things I was taught at Harvard and Durham and Princeton and elsewhere about Formgeschichte I now shake my head and realize I have to leave them behind, or place them under the heading— ‘not so much’. If we really believe ‘a text without a context is just a pretext for whatever we want it to mean’ then a premium must be placed on reading the NT with as little anachronism as possible, reading it in a historically responsible way. Why would we not listen to Papias when he tells us that Mark composed his Gospel according to the rhetorical form known as the ‘chreia’? Sometimes we do not listen because we do not have ears trained to hear the rhetorical overtones.

The documents we have in the NT were primarily meant to be heard, not to be studied as written texts. These are oral texts. No, the phrase ‘oral text’ is not an oxymoron, like, say, the phrase Microsoft Works. Neither Jesus nor the writers of the NT insist– ‘let those with two good eyes, read this’. Most eyes could not read in the NT era according to even the most generous of literacy studies of antiquity. And even the two references in the NT to ‘a reader’ (singular) in Mk. 13.14 or in Rev. 1.3 distinguish between the ‘reader’ (in this case the lector who read it out loud to the congregation) and the hearers. Listen again to Rev. 1.3— ‘ blessed is the one who reads aloud the words of the prophecy and also blessed are those who hear…’

This is one of the primary reasons finding gigantic chiasms in the letters of the NT simply doesn’t work. Big chiasms have to be seen. You can’t pick them out by listening to a linear reading out of a document. Yes an A,B.B,A structure can be aurally discerned if it spans a few verses. The alert ear can pick that out. But frankly Grand Canyon-sized chiasms (or is it chasms?) like one reads about in Ken Bailey’s recent Paul through Mediterranean Eyes tell us far more about the considerable creativity of Ken Bailey than about Paul’s letter to the Corinthians. Giant chiasms are like beauty— they are in the eyes of the beholder. Not so with rhetorical structures in the NT documents. Listen to Duane Watson’s word of caution on this matter:

The chiasm has rightly been seen as structuring individual verses and blocks of texts. However I doubt that chiasm structures entire Pauline epistles (as has been argued for Philippians) especially if it is concluded that Greco-Roman conventions have played a significant role in their construction. Greco-Roman rhetoric did not discuss chiasm and certainly not as an organizing principle of larger works. Besides, the conventions in play for invention and arrangement make chiasm a very difficult form of arrangement to maintain. Greco-Roman rhetoric, as it is incorporated into a speech or a document, is based on a linear unfolding of a series of topics and propositions guided by the exigencies of a rhetorical situation. This approach makes a chiastic arrangement for an entire epistle extremely difficult and unlikely.

Exactly right. But we could have come to the same conclusion simply on the basis that these are oral and aural discourses, meant to be heard by all, not primarily meant to be read except by the lector and a few well-educated Christians in the audience. These were oral texts that HAD, in the first instance, to be read out loud to make sense of where thoughts and sentences and rhetorical units started and stopped. I would suggest this is why Paul entrusted his letters to trustworthy co-workers like a Timothy or Titus or Phoebe, who already knew the contents of the letter they would deliver upon arriving somewhere. And by ‘deliver’ I mean not merely hand over to the literate in a church, but orally deliver upon arrival, just as a herald would read out an ambassadorial letter to the recipients upon arrival.

It helped if a document was composed on the basis of a basic structure of a Greek speech— exordium, narratio, propositio, probatio, refutatio, peroratio. It helped because people already knew this basic Greek speech structure all over the Empire. They knew how to listen for the thesis statement, listen for the final summing up, brace themselves for the ‘sturm und drang’ of a peroration like we find in Ephesians 6. They could listen with anticipation. They knew that most discourses (i.e. the non-epideictic ones) would involve both arguments for and against some key theme or thesis or theses. Even those who could not read a discourse had heard so many of them that they regularly could pick out the parts, and knew what to anticipate, in the same way a child who hears a story today that begins ‘once upon a time…’ can well expect that before they fall asleep they will hear ‘and they all lived happily ever after’ by nodding off time.

Our problem is that we have studied these NT documents as if they were indeed like modern texts. We’ve studied them in the first instance primarily in English. And yet a third of the rhetorical force of a Greek discourse is lost in translation—all the assonance, alliteration, rhyme, rhythm and a host of other oral and aural effects are lost to us unless we have very clever translators indeed.

The recent detailed studies about how ancient manuscripts were composed (see H. Gamble and L. Hurtado), how the book trade arose (see William A. Johnson), and what the characteristics were of an ancient oral culture where literacy at best was about 20% in some quarters, need to inform the way we read the NT. So, I will say again, the NT is full of oral documents. And when we analyze them as oral documents (meant to be read out loud and heard), the light begins to dawn that they are also most profoundly, rhetorical documents, meant to persuade persons about Jesus Christ, meant to preach. Here the Good News friends— the NT is already preacher friendly and preaching ready. It is not merely the basis for the preaching— it contains the preaching or persuasion!

MACRO RHETORIC REVISITED

Since the proof of the pudding is in the eating, it is now time to demonstrate the macro-rhetoric of the NT in some detail. Let’s start with the issue of ethos, logos, and pathos. Any good rhetorical discourse, whether it was deliberative, forensic, or epideictic had to attend to the issues of ethos, logos, and pathos. This was not an issue of micro-rhetoric here or there, but of the macro-structure of the discourse. At the outset of a discourse the issues of authority, establishing rapport with the audience, and attention to what could be called the more surface emotions needed to be attended to. This was in turn followed by a series of arguments (if we have deliberative or forensic rhetoric), or a series of illustrations or displays of things praiseworthy or blameworthy (if we have epideictic rhetoric). All three species of rhetoric concluded with a final harangue, which could involve a summing up of previous arguments, an appeal to the final argument, and in any case the arousing of the deeper emotions such as love and hate. This threefold pattern can be readily found in Paul’s letters, in Hebrews, in 1 Peter, and elsewhere in the NT. It can also be found in the speech summaries in Acts which Luke reports.

A few points of elucidation are crucial. Firstly, as scholars have often noted for reasons they did not fully grasp, Paul in his opening prayers often uses them as a preview of coming attractions in the following letter. Themes that will be played out and dealt with in what follows are mentioned in passing, up front, in these thanksgiving or blessing prayer reports. Why?

It was not an epistolary convention to offer such extended prayers at the beginning of a letter, much less to use them as an occasion to thank the deity for things that would later be discussed or even critiqued at length in the discourse. This is not an epistolary convention at all. A bare perfunctory health wish (‘trust you are well’) is not the same thing as these prayer reports.

IT IS however a rhetorical convention to both establish rapport with the audience at the outset, and while doing that, intimate what the following arguments will in part be about. In other words, Paul is using these prayer reports as exordiums coming as they do normally just after the opening prescript and greeting. Let’s take an example from 1 Corinthians.

I always thank my God for you because of his grace given you in Christ Jesus. 5 For in him you have been enriched in every way—with all kinds of speech and with all knowledge — 6 God thus confirming our testimony about Christ among you. 7 Therefore you do not lack any spiritual gift as you eagerly wait for our Lord Jesus Christ to be revealed. 8 He will also keep you firm to the end, so that you will be blameless on the day of our Lord Jesus Christ. 9 God is faithful, who has called you into fellowship with his Son, Jesus Christ our Lord.

What you notice immediately about this if you already know what’s coming in 1 Cor. 12-14 is that Paul is mentioning some of the very things that are causing the most problems in Corinth— namely their abundant speech and knowledge gifts which they are using in unloving ways. My students call this the sucking up part of the discourse. Paul praises them for the very things they are most enamored with, but which are giving Paul ‘agita’, as the Italians would say. The exordium is meant to function this way, establishing rapport so the audience will be well disposed to hear what follows. Paul is a master at accomplishing this even in a largely problem solving discourse like 1 Corinthians.

What follows this is: 1) the thesis statement in vs. 10, and 2) the brief narration of facts relevant to the following arguments. Again, there was no epistolary convention to state a thesis or proposition and then narrate some pertinent facts. This is a rhetorical convention. And yes, there was some flexibility in how one arranged these things.

Epideictic rhetoric did not require a proposition (and we do not have one in Ephesians) nor a narration of pertinent facts, but these were very important in forensic rhetoric and deliberative rhetoric, though it was fine if the thesis statement came after the narration or before it. The architectonic structure of a speech had some flexibility, and it was also o.k. to mix rhetoric— so for example we have an epideictic interlude in 1 Corinthians 13 in the midst of a basically deliberative discourse. All these things are explained in great detail in the rhetorical handbooks, and Quintilian’s helpful summary of Greek and Latin rhetoric offered towards the end of the first century A.D. shows how these conventions could be used and had evolved over time.

Furthermore, we are increasingly having detailed comparisons done between actual ancient rhetorical speeches and what we find in the NT, not relying just on information from the rhetorical handbooks. Margaret Mitchell set the benchmark for this sort of survey in her doctoral dissertation published in 1991. Fred Long has produced copious evidence on this score. To give but one further example, I have a doctoral student comparing the consolatory rhetoric of 1 Thessalonians, an epideictic discourse, with ancient funeral orations. The results that he is producing are very fruitful in helping us see exactly what Paul is trying to achieve in 1 Thessalonians.

That there are arguments in many of the NT letters, few scholars would dispute. It is not just Paul who was disputatious among the NT writers. What is less well known is that the arguments in, say, Romans are arranged in a particular rhetorical way. In Romans Paul uses the rhetorical method known as ‘insinuatio’. He realizes that the bone of contention in Rome is Jews, Jewish Christians, and among other things the place of Israel in God’s larger salvific plans.

The wise rhetorician will then delay dealing with the bone of contention until he has established not merely rapport, but considerable common ground with the audience so they will listen patiently to the more difficult arguments. Romans 9-11, far from an after-thought, is Paul coming to the point of refuting certain erroneous assumptions about Israel, about its future, about whether Jews have been abandoned by God and replaced by Gentiles, about whether God keeps his promises or not. Romans is a powerful discourse from stem to stern about the righteousness and justice of God and the setting right of human beings, a theme enunciated in the proposition in Romans 1.16-17.

We could walk through the letters of the NT, one after another, and I could point out not merely the rhetorical devices but the varieties of macro-rhetoric used in each case, but I have already done this in a whole series of commentaries, and I see no need to belabor the point here. Lest however we think that rhetoric is only occasionally helpful here and there in the NT in understanding the structure of the discourse, and particularly with Paul and Hebrews and 1 Peter, and Jude etc., I would like to stress that rhetoric helps us in another way as well, in dealing with the big question of why, for example, the language, grammar, syntax of discourses like Ephesians and Colossians differs significantly from Paul’s earlier letters.

We could have avoided dealing with all of those long and lugubrious arguments about how those two letters couldn’t possibly be by Paul because they sound different, have different sentence structures, use different vocabulary and so on had someone paid attention to the fact that these letters are written according to the style of Asiatic rhetoric, the most verbose and hyperbolic form of first century rhetoric. This was entirely appropriate since Paul was writing to the very region where such a rhetorical style was most popular and had originated—- the province of Asia. Paul as a skillful rhetorician was able to vary his style according the audience, and he does so in these documents. Twenty-six line long sentences with lots of adjectives and even some redundancies are no problem in Asiatic rhetoric, as anyone who has read the verbose Nimrud dag stele, in praise of a ruler, will know. As Luke Johnson has said in various of his commentaries, changing of style was a common rhetorical tactic to be persuasive to differing audiences. It’s not a matter of different authors. It’s a matter of flexibility in rhetoric.

Just how well some of the NT writers knew Greco-Roman rhetoric could be demonstrated at length by various samples—- say the famous Hall of Faith epideictic display in Hebrews 11, or the parade example of epideictic the appeal to the virtue of love in 1 Cor. 13, but I want to talk about the ability of someone like Paul to use complex rhetorical figures and techniques such as ‘impersonation’ where one speaks in the voice of another person. The more one studies the NT, the clearer it becomes that various of the NT writers knew rhetoric extremely well and in detail, and were not afraid to use it at length.

As for brother Paul, it will be well here to pass on the conclusions of others. In his seminal essay on Paul’s rhetorical education, and after examining Paul’s use of diatribe, apostrophe, and prosopopoiia especially in Romans, Stan Stowers concluded as follows: 1) Paul had instruction from a grammaticus; 2) he had further study in letter writing and elementary rhetoric, and 3) this included progymnasmatic exercises. Coming at it from the angle of social location, J. Neyrey’s study of Paul’s style and rhetorical finesse concluded that Paul had a tertiary level education that included both rhetorical and philosophical training. Ron Hock came to the very same conclusion based on his examination of Paul’s use of invention and arrangement in the undisputed Paulines. It is time for us to give the apostle to the Gentiles his rhetorical due, not least because it affects the way we interpret a great deal of what Paul says in his rhetorical letters.

RHETORIC ON FULL DISPLAY

Romans 7 demonstrates not only Paul’s considerable skill with rhetoric, but his penchant for using even its most complex devices and techniques. This text proves beyond a reasonable doubt that Paul did not use rhetoric in some purely superficial or sparing way (e.g. using rhetorical questions). To the contrary the very warp and woof of his argument here reflects, and indeed requires an understanding of, sophisticated rhetorical techniques to make sense of the content of this passage and the way it attempts to persuade the Roman audience.

‘Impersonation’, or prosopopoiia, is a rhetorical technique which falls under the heading of figures of speech and is often used to illustrate or make vivid a piece of deliberative rhetoric (Inst. Or. 3.8.49 cf. Theon, Progymnasta 8). This rhetorical technique involves the assumption of a role, and sometimes the role would be marked off from its surrounding discourse by a change in tone or inflection or accent or form of delivery, or an introductory formula signaling a change in voice. Sometimes the speech would simply be inserted “without mentioning the speaker at all” (9.2.37). Unfortunately for us, we did not get to hear Paul’s discourse delivered in its original oral setting, as was Paul’s intent. It is not surprising then that many have not picked up the signals that impersonation is happening in Rom. 7.7-13 and also for that matter in 7.14-25.1

Quintilian says impersonation “is sometimes introduced even with controversial themes, which are drawn from history and involve the appearance of definite historical characters as pleaders” (3.8.52). In this case Adam is the historical figure being impersonated in Rom. 7.7-13, and the theme is most certainly controversial and drawn from history. Indeed, Paul has introduced this theme already in Rom. 5.12-21, and one must bear in mind that this discourse would have been heard seriatim, which means they would have heard about Adam only a few minutes before hearing the material in Rom. 7.

The most important requirement for a speech in character in the form of impersonation is that the speech be fitting, suiting the situation and character of the one speaking. “For a speech that is out of keeping with the man who delivers it is just as faulty as a speech which fails to suit the subject to which it should conform.” (3.8.51). The ability to pull off a convincing impersonation is considered by Quintilian to reflect the highest skill in rhetoric, for it is often the most difficult thing to do (3.8.49). That Paul attempts it, tells us something about Paul as a rhetorician. This rhetorical technique also involves personification, sometimes of abstract qualities (like fame or virtue, or in Paul’s case sin or grace– 9.2.36). Quintilian also informs us that impersonation may take the form of a dialogue or speech, but it can also take the form of a first person narrative (9.2.37).

Of course since the important work of W.G. Kűmmel on Rom. 7, it has become a commonplace, perhaps even a majority opinion in some NT circles that the “I” of Romans 7 is not autobiographical.2 This however still did not tell us what sort of literary or rhetorical use of “I” we do find in Rom. 7. As S. Stowers points out, it is also no new opinion that what is going on in Rom. 7 is the rhetorical technique known as ‘impersonation’.3 In fact, this is how some of the earliest Greek commentators on Romans, such as Origen, took this portion of the letter, and later commentators such as Jerome and Rufinus take note of this approach of Origen’s.4 Not only so, Didymus of Alexandria and Nilus of Ancyra also saw Paul using the form of speech in character or impersonation here.5

The point to be noted here is that we are talking about Church Fathers who not only know Greek well but who understand the use of rhetoric and believed Paul is certainly availing himself of rhetorical devices here.6 Even more importantly, there is John Chrysostom (Homily 13 on Romans) who was very much in touch with the rhetorical nature and the theological substance of Paul’s letters. He also does not think that Romans 7 is about Christians, much less about Paul himself as a Christian. He takes it to be talking about: 1) those who lived before the Law; 2) and those who lived outside the Law or lived under it. In other words, it is about Gentiles and Jews outside of Christ.

But I would want to stress that since the vast majority of Paul’s audience is Gentile, and Paul has as part of his rhetorical aims effecting some reconciliation between Jewish and Gentile Christians in Rome7, it would be singularly inept for Paul here to retell the story of Israel in a negative way, and then turn around in Rom. 9-11 and try and get Gentiles to appreciate their Jewish heritage in Christ, and to be understanding of Jews and their fellow Jewish Christians. No, Paul tells a more universal tale here of the progenitor of all humankind, and then the story of all those ‘in Adam’, not focusing specifically on those ‘in Israel’ that are within the Adamic category.8 Even in Rom. 7.14-25, Paul can be seen to be mainly echoing his discussion of Gentiles in Rom. 2.15 who had the ‘Law’ within and struggled over its demands.9

What are the markers or indicators in the text of Rom. 7.7-13 that the most probable way to read this text, the way Paul desired for it to be heard, is in the light of the story of Adam, with Adam speaking of his own experience?34 Firstly, from the beginning of the passage in vs. 7 there is reference to one specific commandment– ‘thou shalt not covet/desire’. This is the tenth commandment in an abbreviated form (cf. Ex. 20.17; Deut. 5.21). Some early Jewish exegesis of Gen. 3 suggested that the sin committed by Adam and Eve was a violation of the tenth commandment.35 They coveted the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

Secondly, one must ask oneself, who in Biblical history was only under one commandment, and one about coveting? The answer is Adam.36 Vs. 8 refers to a commandment (singular). This can hardly be a reference to the Mosaic Law in general, which Paul regularly speaks of as a collective entity. Thirdly, vs. 9 says ‘I was living once without/apart from the Law’. The only person said in the Bible to be living before or without any law was Adam.

Fourthly, as numerous commentators have regularly noticed, Sin is personified in this text, especially in vs. 11 as if it were like the snake in the garden. Paul says ‘Sin took opportunity through the commandment to deceive me’. This matches up well with the story about the snake using the commandment to deceive Eve and Adam in the garden. Notice too how the very same verb is used to speak of this deception in 2 Cor. 11.3 and also 1 Tim. 2.14. We know of course that physical death was said to be part of the punishment for this sin, but there was also the matter of spiritual death, due to alienation from God, and it is perhaps the latter that Paul has in view in this text.

Fifthly, notice how in vs. 7 Paul says I did not know sin except through the commandment. This condition would only properly be the case with Adam, especially if ‘know’ in this text means having personal experience of sin (cf. vs. 5). As we know from various earlier texts in Romans, Paul believes that all after Adam have sinned and fallen short of God’s glory. The discussion in Rom. 5.12-21 seems to be presupposed here. It is however possible to take egnon to mean ‘recognize’— I did not recognize sin for what it was except through the existence of the commandment. If this is the point, then it comports with what Paul has already said about the Law turning sin into trespass, sin being revealed as a violation of God’s will for humankind. But on the whole it seems more likely that Paul is describing Adam’s awakening consciousness of the possibility of sin when the first commandment was given. All in all, the most satisfactory explanation of these verses is if we see Paul the Christian re-reading the story of Adam here, in the light of his Christian views about law and the Law.39

Certainly one of the functions of this subsection of Romans is do something of an apologia for the Law. Paul is asking, is then the Law something evil because it not only reveals sin, but has the unintended effect of suggesting sins to commit to a human being? Is the Law’s association with sin and death then a sign that the Law itself is a sinful or wicked thing? Paul’s response is of course ‘absolutely not’! Vs. 7 suggests a parallel between egnon and ‘know desire’ which suggests Paul has in view the experience of sin by this knower. Vs. 8 says sin takes the Law as the starting point or opportunity to produce in the knower all sorts of evil desires.40

Stowers reads this part of the discussion in light of Greco-Roman discussions about desire and the mastery of desire, which may have been one of the things this discourse prompted in the largely Gentile audience.41 But the story of Adam seems to be to the fore here. The basic argument here is how sin used a good thing, the Law, to create evil desires in Adam.

It is important to recognize that in Rom. 5-6 Paul had already established that all humans are ‘in Adam’, and all have sinned like him. Furthermore, Paul has spoken of the desires that plagued his largely Gentile audience prior to their conversions. The discussion here then just further links even the Gentile portion of the audience to Adam and his experience. They are to recognize themselves in this story, as the children of Adam who also have had desires, have sinned, and have died. The way Paul will illuminate the parallels will be seen in Rom. 7.14-25 which I take to be a description of all those in Adam and outside of Christ.43

Paul then is providing a narrative in Rom. 7.7-25 of the story of Adam from the past in vss. 7-13, and the story of all those in Adam in the present in vss. 14-25. In a sense what is happening here is an expansion on what Paul has already argued in Rom. 5.12-21. There is a continuity in the “I” in Romans 7 by virtue of the close link between Adam and all those in Adam. The story of Adam is also the prototype of the story of Christ, and it is only when the person is delivered from the body of death, it is only when a person transfers from the story of Adam into the story of Christ, that one can leave Adam and his story behind, no longer being in bondage to sin, and being empowered to resist temptation, walk in newness of life, as will be described in Rom. 8. Christ starts the race of humanity over again, setting it right and in a new direction, delivering it from the bondage of sin, death, and the Law. It is not a surprise that Christ only enters the picture at the very end of the argument in Rom. 7, in preparation for Rom. 8, using the rhetorical technique of overlapping the end of one argument with the beginning of another.44

Some have seen vs 9b as a problem for the Adam view of vss. 7-13 because the verb must be translated ‘renewed’ or ‘live anew’. But notice the contrast between ‘I was living’ in vs. 9a with ‘but Sin coming to life’ in vs 9b. Cranfield then is right to urge that the meaning of the verb in question in vs. 9b must be “sprang to life” 45 The snake/sin was lifeless until it had an opportunity to victimize some innocent victim, and had the means, namely the commandment, to do so. Sin deceived and spiritually killed the first founder of the human race. This is nearly a quotation from Gen. 3.13. One of the important corollaries of recognizing that Rom. 7.7-13 is about Adam (and 7.14-25 is about those in Adam, and outside Christ), is that it becomes clear that Paul is not specifically critiquing Judaism or Jews here, any more than he is in Rom. 7.14-25.

Vs. 12 begins with hoste which should be translated ‘so then’ introducing Paul’s conclusion about the Law that Paul has been driving toward. The commandment and for that matter the whole Law is holy, just, and good. It did not in itself produce sin or death in the founder of the human race. Rather sin/the serpent/ Satan used the commandment to that end. Good things, things from God, can be used for evil purposes by those with evil intent. The exceeding sinfulness of sin is revealed in that it will even use a good thing to produce an evil end– death. This was not the intended end or purpose of the Law. The death of Adam was not a matter of his being killed with kindness or by something good. Vs. 13 is emphatic. The Law, a good thing, did not kill Adam. But sin was indeed revealed to be sin by the Law and it produced death This argument prepares the way for the discussion of the legacy of Adam for those who are outside of Christ. The present tense verbs reflect the ongoing legacy for those who are still in Adam and not in Christ. Rom. 7.14-25 should not be seen as a further argument, but as the last stage of a four part argument which began in Rom. 6 being grounded in Rom. 512-21, and will climax Paul’s discussion about sin, death, and the Law and their various effects on humankind.

It will not be necessary for us to go into as much depth with Rom. 7.14-25 as we have with the tale of Adam in 7.7-13. Rather we will focus on the points of rhetorical significance that should have guided the interpretation of this text all along. Firstly, once it is realized that there is a fictive ‘I’ being used in 7.7-13, to create a ‘speech in character’ then it requires a change of rhetorical signals at 7.14 or thereafter if that were to cease to be the case in 7.14-25. We have no such compelling evidence that Paul is now using ‘I’ in a non-fictive way in these verses now under scrutiny. There is, it is true, a change in the tenses of the main verbs, here we have present tenses, signaling that Paul is talking about something that is now true of someone or some group of persons, but it must be some group that has an integral connection with the ‘I’ of 7.7-13.

Fortunately Paul had already set up such a link in Rom. 5.12-21, in particular at the outset of that synkrisis or rhetorical comparison—one man sinned and death came to all people, but not just because he sinned but also because they all sinned. The link has been forged, and we see here how it is played out as Adam’s tale in 7.7-13 leads directly to the tale of all those who are in Adam in 7.14-25. Kasemann puts the matter aptly: “Egō [here] means [hu]mankind under the shadow of Adam: hence it does not embrace Christian existence in its ongoing temptation…What is being said here is already over for the Christian according to ch. 6 and ch. 8. The apostle is not even describing the content of his own experience of conversion.” This comports completely with Rom. 7.5-6 where Paul contrasts what the audience once was before they became Christians, and what they are now— free in Christ. It comports as well with what Paul stresses in Rom. 8.1-2 where he tells us that the Spirit has already set the believer free from the law of sin and death.

It is telling that most of the Church Fathers thought as well that Paul was adopting and adapting the persona of an unregenerate person, not describing his own struggles as a Christian. Most of them believed that conversion would deliver a person from the dilemma describe here, deliver them from the bondage to sin or the law of sin and death, as Rom. 8.1-2 puts it. But what about the reference to the struggle with the ‘law of the mind’ here? Does not that suggest a person, perhaps a Jew, under the yoke of the Mosaic Law? While not an impossible interpretation of the struggle described here, there is a better and more likely view if we are attentive to the rhetorical signals of the whole document. In Rom. 2.15 Paul is quite explicit that Gentiles not beholden to the Mosaic covenant or its Law, nonetheless have the generic law of God written on their very hearts, and therefore they do from time to time do what God requires of them.

Notice that the struggle described in Rom. 7.14-25 is between a law residing in one’s mind, and a quite different ruling principle residing in one’s ‘flesh’ or sinful inclinations. Nothing is said here about rebellion against a known external law code, nor is the book of the Law nor Moses mentioned here. Remember too, that it was said that even Adam himself had a singular commandment of God to deal with, well before Moses, such that when Adam violated that one commandment sin and death reigned from Adam to Moses, even prior to the existence of the Mosaic code (Rom. 5.14). Notice the difference between Rom. 7.14-25 and debates in Rom. 2-3 with the Jewish teacher over the meaning of the external Law code.

It is thus most likely that we have here a more generic description of the condition of those who are in Adam, and are fighting but losing the battle with sin in their lives. The only way out of their dilemma is deliverance. Paul is speaking as broadly as he can in this passage, addressing the human plight outside of Christ in general, and is not singling out Jews for special attention here. That would have been rhetorically inept in any case since the great majority of his audience for Romans is likely Gentiles (see Rom. 11.13).

We must bear in mind as well, that we are dealing with a Christian interpretation of a pre-Christian condition. Paul does not assume that this is how either Gentiles or Jews themselves would view the matter if they were not also Christians. But clearly Gentiles could relate to this discussion. For example, Ovid, in his famous work Metamorphoses 7.19-20 speaks in very similar terms of the struggle with sin: “Desire persuades me one way, reason another. I see the better and approve it, but I follow the worse.” Even closer is the words of Epictetus—“What I wish, I do not do, and what I do not wish, I do.” (2.26.4). Paul has not traipsed into terra incognita for his largely Gentile audience, rather he is standing on familiar ground. The effect of law, law of any sort, on a fallen human being, whether the law of the heart, or the law in a code, is predictably the same, in Paul’s view.

In the earlier parts of Romans, and especially in Rom. 2-3, Paul was resorting to the rhetorical device of the diatribe—a rhetorical debate with an imaginary interlocutor. Rom. 7.7-25 has just a taste of that at Rom. 7.25a where Paul himself, in his own and most pastoral voice responds to the heart cry of the lost person—“Who will deliver me from this body of dead?” His answer is swift and powerful—“Thanks be to God – through Jesus Christ our Lord!” What was lost on Luther is that the voice in vs. 25a is not the same voice as the one which preceded it, or indeed which follows it in 25b. What was lost on Augustine is that this is not Pauline autobiography however well it may have suited Augustine. It is to Augustine and Luther that we owe being led down the wrong garden path in the interpretation of this text, and in some cases led to a wrong view altogether of Pauline anthropology.

At the end of Romans 7, Paul is following a well known rhetorical technique called chain-link, or interlocking construction, which has now been described in detail, with full illustration of its use in the NT by Bruce Longenecker. The basic way this technique works is that one briefly introduces the theme of the next argument or part of one’s rhetorical argument, just before one concludes the argument one is presently laying out. Thus in this case Rom. 7.25a is the introduction to Rom. 8.1 and following where Paul will once more speak in his own voice in the first person. Quintilian is quite specific about the need to use such a technique in a complex argument of many parts. He says that this sort of close-knit ABAB structure is effective when one must speak with pathos, force, energy, pugnacity (Inst. Or. 9.4.129-30). He adds “We may compare its motion to that of men, who link hands to stead their steps, and lend each other their mutual support” (9.4.129). Failure to recognize this rhetorical device where one introduces the next argument before concluding the previous one, has led to all sorts of misreadings of Rom. 7.14-25.

As Longenecker goes on to stress, this reading of Rom. 7.25a comports completely with the thrust of what has come immediately before Rom. 7.7-25 and what comes immediately thereafter. He puts it this way: “Paul has taken great care to signal the transition from Romans 7 to Romans 8: first by contrasting the ‘fleshly then’ and the ‘spiritual now’ in 7.5-6 two verses which provide the structural foundation for the movement from 7.7ff. and 8.1ff., and second, by introducing the ‘spiritual now’ in 8.1 with the emphatic ‘therefore now’ (ara nun). Such structural indicators are strengthened further by the intentional inclusion of a thematic overlap in 7.25….Since in Paul’s day chain-link construction was not an uncommon transitional device in assisting an audience…the placement of 7.25 within its surrounding context would not have been unusual or confusing. It would not have been seen as a structural anomaly requiring either textual reconstruction…or psychological explanation. Instead it would have been seen as a transition marker used for the benefit of Paul’s audience.” As an aside it is worth saying that Origen offers this same sort of analysis on Romans 7 as ‘impersonation’ back in hoary antiquity.

In short, if Paul can go to these sorts of lengths to use rhetorical conventions to convict and persuade a Roman audience that he has not even met, we may be sure that it is a mistake to under-estimate what was rhetorically possible for Paul and other writers of the NT. Not all of them had Paul’s skills and finesse. But almost all of them had some knowledge and made some use of not just micro-rhetoric but also macro-rhetoric, and it is high time we were in more agreement with Origen and Chrysostom and Jerome and Melanchthon and others on this score.

AND SO??

What I have sought to show in this lecture is that one ignores Greco-Roman rhetoric at one’s peril if one wants to understand the NT. It is not enough to have a nodding acquaintance with minor rhetorical devices and how they work, say the negative rhetorical questions at the end of 1 Cor. 12 all of which require the response no. (‘Not all speak in tongues, do they? Not all prophesy do they?). If you want to understand how Paul’s arguments work (why he appeals, for example, first to experience, then to Scripture then to customs and traditions in that order in both Gal. 3 and 1 Cor. 11), why they are arranged as they are, or why there is so much redundancy (i.e. amplification) in 1 John, or why there is so little future eschatology in Ephesians (its epideictic rhetoric— the focus is on what can be praised in the present), or why the Pastoral Epistles have been wrongly called disjointed ethical snippets (answer—because Dibelius and his followers failed to notice what we have is enthymemes in the Pastorals, and you have to supply the missing member of the syllogism), or why the so-called pronouncement stories in Mark are really classic rhetorical chreia, as Papias said in the first place, or why Luke’s prologue in Lk. 1.1-4 takes the form it does, or why the speeches in Acts take the rhetorical forms they do, or why ‘synkrisis’ is used so eloquently and powerfully in Hebrews, then its time to give rhetoric its due. And it’s time for me to use the rhetorical trope the author of Hebrews uses in Hebrews 13 when he says ‘In conclusion, I have spoken to you briefly…..’

In Paul’s famous rhetorical tour de force speech in Acts 26, given before Agrippa and Festus, there comes a juncture where Festus interrupts and exclaims: “You are out of your mind. Too much learning is driving you insane.” I thank you for not interrupting this ‘brief’ lecture with that interjection this evening. ☺ In closing, I rather hope instead you will reply along the lines of King Agrippa— “almost thou persuadest me to become a Christian” or in this case “a Christian rhetorician.” Thank you very much.