Poetry is a dying art. Few people write it, read it, or would even know how to if they tried. It requires a heart, an imagination, and the ability to sit within a tension.

In today’s sound-bite culture people have lost the essential ability to live within a poem

This is a deeply tragic cultural illiteracy.

Being unable to dwell in poetry means you are unable to dwell in the world of the Bible because so much of the Bible is poetry.

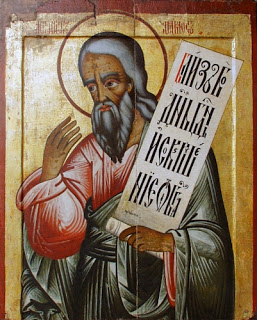

Obviously there are poems that make up the Psalms, but poems also are scattered throughout almost every book of the Bible in one way or another. The prophets are almost entirely written in poetic form and some of the deepest theology in the the new Testament is created employing forms of parallelism in the Greek text that dwell on the rich heritage of Hebrew Poetry (look at Philipians 2 for example).

Jesus himself used poetry more then any other source to frame and define his action to the Jewish world he inhabited.

Like I said, understanding poetry is essential to understanding the Bible.

I have had difficulty learning how to read poetry poetry in the Bible. For many years I struggled just to get a grip on what the prophets were saying. It’s a deep well that it’s hard to master completely, but in reading about poetry I have the paradigm of Parallelism as a great starting place to begin.

Parallelism is at the heart of much of Hebrew Poetry.

What parallelism basically means is that one line of poetry has a direct relationship with another line of poetry, and must be read in that relationship in order to be understood.

The meaning of the passage is not just in the lines themselves but in the tension created between the two lines. It’s like creating a perception of depth by seeing a truth through both eyes.

Parallelism can function in a number of ways. My teacher, Bob Hubbard, helped me to understand this better using the symbols =

If a line of poetry is = to the line that follows it then the parts of the lines are interchangeable. The second line ECHOES the first line.

An example of this kind of poetry can be found in Amos 8:10

- I will turn your feasts into mourning

- and all your songs into lamentation;

- Will not the day of the LORD be darkness,

- not light–pitch-dark, without a ray of brightness?

If a line of poetry is < to the line that follows it. The first line is used to introduce the second line, and the second line expands or completes the first line.

This can be used to continue the first line, compare something in the first line, intensify something in the first line, so specify something in the first line (this can be spatial, explanatory, for dramatic effect, or give the purpose of the first line).

- Jeroboam will die by the sword,

- and Israel will surely go into exile, away from their native land