This reflection was presented as a weekly Meditation at Phillips Exeter Academy on October 17, 2012. The meditation began with a recording of Paul Simon singing Look for America, from the album: Concert in Central Park.

All my life, in one way or another, I’ve been looking for America, for what it means to be human here. And I gravitate to various kinds of folklore, story telling and rituals, ways in which people survive and share their hope and groaning.

This fall I began to write a blog of reflections about this looking, and about the gospel readings which have been part of my weeks for over three decades now. I chose the name for the blog, The Bite in the Apple, in a sudden burst of inspiration. The name works for me. But then I realized, while everyone in the world knows what the apple is, there are all kinds of assumptions about what it means, and what it means to me will not be apparent to anyone unless I write a bit about it. This, then, is my personal journey into the meaning of Eden, a myth that is woven into the cultural fabric of America.

There’s nothing older than Eden, in human knowing. And about Eden, we know nearly nothing.

In each of us, and I think in every creature, too, there is a dream of an idyllic place, a true home where sorrow and sighing are no more, and where every good thing has root; a place from which we have inexplicably gotten lost. That’s Eden, the longing and the lostness.

The story of Eden is ancient, separated from the world we know. And at the same time it is as close as a heartbeat. Adam and Eve are older than Judaism, older than we can possibly imagine. They live in a time outside history. And they also live inside us, they live in an eternal now.

The tale of Eden has outlasted empires. And been reduced to a children’s story. Yet it is terrifically powerful in cultural battles in our own time. Laws against sex between people of different races or the same gender have their root in Eden. People have been put in prison because of Eden. And men have been excused from responsibility for acting on their sexual urges because of Eden, in the authorized theology of St. Augustine, who wrote the original Eve-made-me-do-it defense, which is official doctrine for Catholics.

The theological doctrine of Original Sin has a history filled with political intrigue, the rise and fall of empires, the buying of votes in church councils, bribes, threats and chicanery.

The best of books describing this is Adam, Eve, and the Serpent: Sex and Politics in Early Christianity, by Elaine Pagels, who teaches at Princeton. You can get it online, and it is a real page-turner, you’ll have a my-G0d-I-can’t-believe-this-guy-is-gonna-get-away-with-this reaction on nearly every page.

Trees

At the center of Eden, where Time begins, is the Tree of Knowledge, which bears the fruit of ultimate desire. Sometimes that desire is called eternal life, and sometimes it is called wisdom. The words are used interchangeably in the story. But wait, you may want to say, I don’t see how . . . and that’s the point. We all have to wait to see how.

In the Christian book of tales, a quite similar place to Eden, called New Jerusalem, exists at the end of time. At its center stands a tree whose roots span four rivers, and whose leaves have the power to heal nations.

In between the first story and the last is a journey marked by trees. In the Jewish Tanach, there are trees as well as animals on the Ark.

In the Book of Numbers there is a parable about trees, in which the lowly mustard bush becomes king over the mighty cedars of Lebanon. The fig tree, an icon for Israel in the Hebrew Bible, figures prominently in the teachings of Jesus, and before he dies he prays in an orchard of fig trees.

Elijah is sheltered by a tree on his wild flight up Mt. Horeb. The Messiah will spring from the stump of the tree of Jesse. The Cross is considered a tree that bears the fruit of Resurrection. The kingdom of heaven is like a tree, Jesus says.

Jeremiah Ingalls of Newburyport, an early New England choirmaster, wrote a shape-note hymn in the 1700s, calling Jesus Christ the Appletree. It’s still sung today. The first verse is:

The tree of life my soul hath seen

Laden with fruit and always green

The trees of nature fruitless be

Compared with Christ the apple tree

Each holy tree bears some kind of wonderful fruit: wisdom and life from the Eden Tree; honesty from the lowly mustard bush; protection for Elijah; food in all seasons from the fig; shelter for all in the kingdom tree; hope from the cross.

We mortals have bitten deeply into these fruits, and the taste of them has bitten deeply into us.

Apples

There are four major apple icons I can think of:

Eden’s Apple

the Apple that fell on Isaac Newton’s head

Steve Job’s Apple computer

and the Big Apple, New York City.

And I think they are all related.

They are related the way the science of the heavens is related to geometry and to poetry, and to the history of human experience of dark and light. These four apples have shaped and changed the culture of the western world. All of them are archetypes of experience, and are mythic and real, in their hold upon us.

The Eden Apple, though mythic, could not be more real in its hold upon us.

Newton’s theory of gravity inaugurated the age of science, but his Apple may be a fiction.

Steve Job’s computer has become the icon of our age, and we all live in (and this essay comes to you from) cyberspace, an unreal world that has become our dominant reality.

New York, as the Big Apple, offers all these bites of wisdom, and the consequences of knowledge that Eve and Adam, Isaac Newton, and Steve Jobs tasted. New York holds the dreams of millions, offers a chance to acquire vast knowledge about life and death, and is full of stories about those adventures. As is Eden, always.

And some of the tastes are heavenly. And some of the bites are hell.

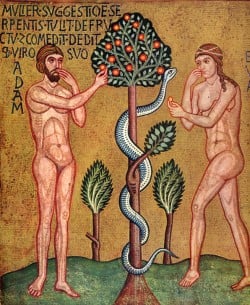

Adam and Eve

used with permission

Eden is a complex creation story, containing a refrain of Godly blessing:

It is good is pronounced over everything: the days, the nights; the heavens, the earth; the trees, the fruits, the creatures.

And so the Original Name of everything is Good.

The human creature, both the man and the woman, are good in a wonderful way: at their creation God says, “male and female we created them, in our own image we created them.”

This litany of goodness opens into a tale about a slithering serpentine tempter, who knows more than humans do. And in this, the Tempter is God-like. Is the Tempter a Trickster figure, who is really part of God?

Is there something in the Garden that was not made by God?

If the answer to that is No, then the Tempter is part of the Good that is the Garden.

If the answer is Yes, then the primary question becomes, Whose Garden Is This?

Knowledge is a precious fruit. It marks the boundary between childhood and adult life. Childhood is replete with gifts, mostly from parent-guided living. Adulthood is not a gift, it is something a child takes hold of and becomes. So, too, knowledge is something taken hold of, not something given. Parents say to their children, Don’t touch the stove! Hot! Hot! But as they grow, children do touch the stove. There is never a day when the parent says, OK, now you may touch the stove. The children decide when.

The way to adulthood, for Adam and Eve and us, has to be a road taken. It cannot be a road not taken. And it cannot be a trip planned for them. In the tale, God speaks the Don’t which will eventually be overcome. In the journey to adulthood, there is no going back. Once a child is weaned, once a child can walk, once a child is sexually mature, there is no going back.

The fruit of knowledge holds sorrow as well as joy, regret as often as delight, hardship as part of wonder. These depths are named by God, after the humans have eaten the apple. Now you will know . . . . St. Augustine views this as a curse. But it may just be wisdom, spoken.

Parents discover heartbreak, hardship and regret, as well as joy, wonder and delight, in their children. Artists learn this in their art, musicians in their music, bakers in their bread, preachers in their congregations, saviors in the souls they love. God learns all these things through us, says the tale of Eden. And this is just part of the way in which wisdom is life and death.

Eating the Apple

In the great paintings of the Fall, the Eating of the Apple is portrayed in a number of different ways. I looked at an immense array when I was choosing an image for my blog.

In the great paintings of the Fall, the Eating of the Apple is portrayed in a number of different ways. I looked at an immense array when I was choosing an image for my blog.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, whose image I chose, paints the Eating of the Apple as an intimate moment, Adam with his arm around Eve, Eve holding the apple up to him as they share this meal. But others show the apple in the Serpent’s mouth and the serpent putting it into Eve’s. Or Eve pushing the apple at an alarmed Adam. Or Adam and Eve greedily grabbing apples with both hands, from opposite sides of the tree, not looking at each other at all. Or Eve in ecstasy as the serpent wraps around her naked body, while Adam, still innocent, looks blankly on. In some paintings Adam and Eve stand far apart, in others, close together. In some, she is near the serpent, he is alone.

And there is even a stylized image found in both Roman and Greek art, of two handsome men who look much alike, one is Adam, you know him by his nakedness, the other handsome fellow has a brown beard and brown robe, and they are smiling into each other’s eyes while the robed one touches an apple. They stand close together, while Eve, in these images, stands apart from them, and does not look at them. She looks like Fran the Robot in the insurance commercials, with her switch off. She’s just not part of the action. Well, what’s this image?

In Rome, the captions say it is God warning Adam about the tree. But that isn’t a convincing caption, because both men are smiling gently at each other. And in Greece, a several centuries older Christian culture, and a much more tolerant form of Christianity, the robed man is said to be Jesus Christ. What’s he doing in the Garden? And why is he smiling on Adam while touching an apple? Is he promising he can fix it, don’t worry? Or saying he is the wisdom of the tree?

Neither of these captions is convincing, and both are surely later guesses.

These paintings are about desire. And the Apple is about desire. Whoever the robed man is, it seems that the conservative line, Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve, is not, in fact, the way the story has always been visually presented in altar art.

Adam and Eve in America

James Carroll, in his book Jerusalem, reports that the immigrants who filled the ships that filled America held the dream of the New Jerusalem, the reclaimed Eden, so powerfully that nearly 200 cities and towns are named New Jerusalem, most commonly in the shortened form of Salem, which means peace in Hebrew and in Arabic. From Salem MA and Salem NH to Salem OR, settlers desired not just a new chance, but a better world to live in. And these settlers ranged from Puritans to Sweet Betsy from Pike.

James Carroll, in his book Jerusalem, reports that the immigrants who filled the ships that filled America held the dream of the New Jerusalem, the reclaimed Eden, so powerfully that nearly 200 cities and towns are named New Jerusalem, most commonly in the shortened form of Salem, which means peace in Hebrew and in Arabic. From Salem MA and Salem NH to Salem OR, settlers desired not just a new chance, but a better world to live in. And these settlers ranged from Puritans to Sweet Betsy from Pike.

In the midst of all this fever for redemption through migration, Adam and Eve came to America, too. Serious academics in the literary field have written about the American Adam for years. For whatever reasons, Adam and Eve split up before they stepped ashore (now there’s an American experience, in fact one of the very first freedoms: the Puritans enacted the first divorce law in the western world a short 8 months after landing in Boston.)

Adam has walked through America alone in all manner of guises. He’s become a stock character in our literature, TV series, and films. He is not tied down, no wife and kids. He is Natty Bumppo, living in the wilderness outside the settlements of British and Natives. He is Huckleberry Finn and he is also Jim, rafting the Mississippi river between towns where this cross-race friendship would still not be allowed.  He is the Lone Ranger, naming injustice, and an endless array of detectives, FBI agents, CSI investigators, and recently Patrick Jane and Castle, non-violent police advisors with special wisdom for naming good and evil.

He is the Lone Ranger, naming injustice, and an endless array of detectives, FBI agents, CSI investigators, and recently Patrick Jane and Castle, non-violent police advisors with special wisdom for naming good and evil.

In all of this, Adam keeps his Original Job, tending the Garden of Good and Evil. He has some real flesh, too, men who’ve ingested the apple of knowledge: Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Thomas Edison, Andrew Carnegie (who built libraries all over America), all these men are icons of wisdom. Martin Luther King, Jr, used his bites of wisdom to bring freedom to the oppressed, and is perhaps the best American Adam of all, though some, especially here in NH, see him as the Serpent in the story, tempting people to break rules and eat what they should not be eating.

There must be others. Who would you name?

Eve, too, got off the boats, and has survived in America on her own. She has retained her sexiness, her smartness, her power to persuade, and her goodness. I think she is Scarlett in Gone With the Wind, Dorothy in Oz. She is Amelia Earhart,  Marilyn Monroe, Helen Gurley Brown and Oprah, each of whom is part fiction and part real, and each of whom lives by her wits, has bitten into the apple of forbidden experience, and breaks open our thinking by the way she lives.

Marilyn Monroe, Helen Gurley Brown and Oprah, each of whom is part fiction and part real, and each of whom lives by her wits, has bitten into the apple of forbidden experience, and breaks open our thinking by the way she lives.

In America, Eve saves the farm and navigates changing worlds. She seduces slithering political serpents in every industry, which gets her through closed doors – and then many women follow along behind her. And she gets special knowledge and power by taking things she is not supposed to take – shoes, money, men, fame, control.

She is outrageous and she opens the doors of our closed world to new experiences.

Eden in America

I heard the writer Margaret Atwood say that the American longing for Edens is evident in the proliferating theme parks that dot the country, offering fantasy escapes.

But I think there is a deeper and wiser way that Eden lives among us. About ten days ago I was lucky enough to get to the New Yorker Festival, where I saw a pre-release screening of the movie, Cloud Atlas. In the film six stories are interwoven, and they take place over 300 years, from the mid – 1800s to the future, a hundred and fifty years from now. Each of these stories is a tale of The Fall, and each of them takes place in the fullness of an era which is a like a ripe garden.

In each era temptation comes to an Adam or an Eve in the form of someone who is forbidden, despised, horribly bound. The forbidden are people we all know. A slave, in the 1840s. A young gay man, living in the Edwardian era. An older man who has been tricked into a home for the demented in our own era, and is a prisoner there. A young black entertainment reporter who trips over dangerous information and her life is on the line because of it, in our own time. A cloned Korean worker who is sexually abused in a future world, a staple nightmare of sci fi. A man and woman in a post-Apocalyptic garden world, the man from survivors who have become primitives, the woman from a highly advanced society – both societies are endangered, and they are forbidden to interact. In each tale a bond of love forms, and the Adam or the Eve, in the strength of this love, takes a risk that is huge, sometimes involving serious injury and sometimes costing their life, in order to leave that world and save the one they love. Love pushes them to the borderland, and urges them to move on, into a new time.

This is what the Eden tale does – it propels us out of our comfort zone, fortifies us for a journey into an unknown time and a new world, and helps us claim one another in a journey that will sustain us in the long search for freedom.

Graceland

Paul Simon’s Graceland is a national anthem for our search for Eden, our search for grace and freedom. Here are the words:

Graceland

in Memphis Tennessee

I’m going to Graceland

Poorboys and pilgrims with families

and we are going to Graceland

My traveling companion is nine years old

He is the child of my first marriage

But I’ve reason to believe

We both will be received

In Graceland

She comes back to tell me she’s gone

As if I didn’t know that

As if I didn’t know my own kid

As if I’d never noticed

The way she brushed her hair from her forehead

And she said losing love

Is like a window in your heart

Everybody sees you’re blown apart

Everybody sees the wind blow

I’m going to Graceland

Memphis Tennessee

I’m going to Graceland

Poorboys and pilgrims with families

And we are going to Graceland

And my traveling companions

Are ghosts and empty sockets

I’m looking at ghosts and empties

But I’ve reason to believe

We all will be received

In Graceland

There’s a girl in New York City

Who calls herself the human trampoline

And sometimes when I’m falling, flying

Or tumbling in turmoil I say

WHOA, so this is what she means

She means we’re bouncing into Graceland

And I see losing love

Is like a window in your heart

Everybody sees you’re blown apart

Everybody feels the wind blow

In Graceland