Stuart Inman has been a respected and revered friend and colleague for a long time now and is one of those people who has experience and knowledge aplenty. From his earliest involvement with Wicca under the tutelage of Alex Sanders, immersion in Tibetan Buddhism, to becoming one of the foremost exponents of Traditional Witchcraft and a guardian of the 1734 tradition and method, Stuart is an authority on Surrealism and also the magister of the Clan of the Entangled Thicket.

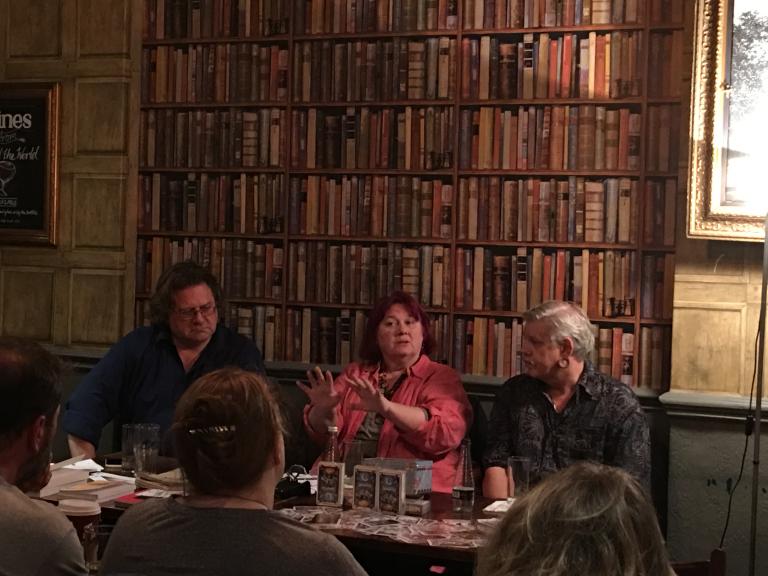

BTPM (By The Pale Moonlight): Thank you for agreeing to be quizzed. I have decided to interview some few individuals who have influenced and inspired me. In addition, these are people whom I believe have much of great value to contribute and the community would benefit from. In sharing a part of your experience and perspective, the world is enriched.

SI (Stuart Inman): Thanks for asking! As for influencing you, the process has been mutual, I have always benefited from discussions with you.

BTPM: Firstly, can you tell us a little bit about your background and foundation?

SI: Well, I grew up in the suburbs of London, a mostly godforsaken place called Feltham. My first intimation of these interests was when I took up yoga, probably aged 13, then two years later I came across two books, Gardner’s “Witchcraft Today” and Maya Deren’s “Divine Horsemen”. From then on there was no stopping me. I tried my first evocation a few months later, using Idries Shah’s “Secret Lore of Magic”. It was probably a more than usually half-arsed attempt to call up Sytry. I didn’t notice any effect at the time, but about an hour later, my body started to tremble uncontrollably and for no obvious reason. I can’t swear that this was the consequence, but given my state of knowledge at the time, if it was, I was probably very lucky I was not more successful!

After that, I discovered the Golden Dawn in Torrens’ little book, W.E. Butler’s “Apprenticed to Magic”, which led to my first ever magical diary, and then Crowley, in one of Symonds’ books, not sure which one now, and Justine Glass’s book on Witchcraft, little knowing it would become important to me many years later. Then I came across “King of the Witches”, June Johns’ biography of Alex Sanders. This was a great turning point for me as I became fascinated by the book, and desperately wanted to meet Alex Sanders, (I was still only 15 when I resolved to do so.) So I left school at the age of 17 and a couple of weeks later went up to London to meet him.

BTPM: Having studied with Alex Sanders, could you share some of your experiences?

SI: Of course, although I’m not sure where to begin. I first visited in July 1971, the week of Jim Morrison’s death. I was invited to an informal meetup in Kensington Gardens that Sunday and from that started to attend open meetings and lectures. In January, Alex asked if I wanted to be initiated and I was in February 1972. Apart from a few months when I was unable to go there, I was a member of the coven until Alex and Maxine broke up in 1973. Not all that long, but very intense. Apart from the Wiccan circles for both esbats and sabbats, there were ‘development circles’ which in retrospect seemed like a mix of spiritualism with something more ’shamanic’ for lack of a better term. Then there were lectures, I remember one sequence on tarot and another based on Iamblichus’ “On the Mysteries”. There seemed to be quite a lot of visits to the pub in-between and we were expected to be able to function in every way after a couple of pints. It wasn’t always easy…

I remember a visit from Walter Johns, who had apparently been Aleister Crowley’s favourite herbalist, and I especially remember that he had Oil of Rhodium; also, the press would occasionally turn up, especially News of the Screws (Ed. News of the World, a notorious British tabloid). Although Alex enjoyed publicity, they were often there covertly, at the open meetings, to report on anything sensational. Alex’s sense of humour could trip him up sometimes, on one occasion he made a joke about chickens which led to a whole expose about animal sacrifices, even though he’s been talking about getting one from the supermarket! A News of the Screws reporter had been at the open meeting and filled a couple of pages with this stuff.

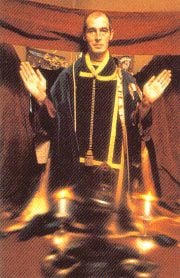

One day, actually Good Friday, Alex asked me to go to a magic shop for him, not an occult store, a place that sold tricks and practical jokes. He wanted a mask, a clear plastic one with a smiling face. A week later it had become the first version of The Aztec, which can be seen in that fire ritual online.

BTPM: Was there a particular part of Alex’s teachings that remains with you or that you feel should be reiterated today?

SI: One of the things that really stuck with me was a series of lectures on Iamblichus. This was basically Alex reading out passages from the Thomas Taylor translation and then explaining what he could. He emphasized how this was a real magical voice from nearly two thousand years ago, a voice of authentic tradition.

BTPM: What drew you from Wicca and towards Buddhism, and what value did you learn from that quarter that you consider relevant to modern pagans?

SI: It’s very complex really; the breakup between Alex and Maxine affected everybody around them. I was feeling quite depressed for a while. Then, as I started to visit Alex in Bexhill, I saw something that repeated itself over several times in a way I’d never seen in London. Too many people were hangers-on, waiting for Alex to do something. They didn’t do magic, they waited for it to happen, for Alex to happen. He hated it, but invited it at the same time. It was flattering and invited his inner showman as much as his inner shaman to perform.

So I felt a kind of disillusionment, partly with Alex, partly with the state of my spiritual life and really, life altogether. Buddhism seemed like a way out, a negation of life, with all that talk of the end of suffering. I found myself reading a load of tantric texts though, which spoke of a fantastic joy of being that seemed very distant to my state of mind.

I discovered a Tibetan Buddhist meditation centre in Essex and booked a weekend there. At the time I was working at the British Library when it was still at the British Museum building in Bloomsbury. In the mornings we had to collect ‘house keys’ to get around the building, and one morning I was in the queue to collect my house key and there was a tall oriental man in front of me who seemed strangely familiar. I realized he was the same man as in the photo of the Lama in the retreat centre leaflet. I introduced myself and found this was indeed Lama Chime Rimpoche. Some months I took refuge with him and started to study Buddhism with some seriousness. Not, I have to say enough seriousness, I was a rubbish student really, I was very serious about it all, but lacked real focus. However Chime became a friend as well as teacher, he was still relatively young, in his mid to late 30s, a snappy dresser. He was also the whole of the Tibetan Section of the British Library and was cataloging a vast number of books and manuscripts, many of which had been looted during the Younghusband Expedition. Curiously, this act of pillage had saved some precious works, thought to have been lost during the Chinese invasion.

I was aware that Tony Visconti was a student of Chime’s , although I never met him, and I remember one day walking to the tube with Chime and seeing a poster for Bowie’s latest album, ‘Lodger’, and Chime saying casually “Oh, David Bowie, he’s a friend of mine”! There’s a lot about that I only learned of when Bowie died and Chime made a very moving video tribute.

I think that what I really learned during that time was something about a world view, not exactly the Buddhist view, in any doctrinaire way, but if you like, some tiny kernel of the view of meditation. It’s neither separated from the world, nor bound to it, somehow both passionate and dispassionate. This became an issue for me several years later, when I suddenly felt the most desperate need to learn meditation properly. I contacted Chime and we arranged that I do very basic Shamatha or Shi-ne meditation under his supervision, which I did faithfully for something over a year before moving on to Vipassana or Lagthong, Insight meditation. This has remained essential to my well-being and has sustained me in difficult times. It has also helped develop and grow my awareness. Here I am reminded of a meditator friend from that time who said the same thing and I pointed out to him that he was possibly the most absent-minded person I knew, to which he retorted “Yes, but without meditation I’d be very much worse.” I now know the same is true of me. If I say my awareness has greatly expanded due to meditation, I don’t mean I’m anything amazing; I just manage to avoid too much idiocy!

As for what’s relevant for modern pagans, I can’t really say, I’m not a pagan! I do think that the basic practice of mindfulness is very useful for anybody, even in its modern, secular and rather sanitized version, as long as it is not too resolutely corporate, and many modern pagans could do with that, or else a kick up the arse, or possibly both. But then so could I, much of the time, so we may yet develop an arse-kicking circle of awareness, who knows?

Can you tell us how you first came into contact with Joe Wilson, founder of the 1734 Tradition of Witchcraft, and give us a little bit of an appreciation of what Joe was like?

SI: We have to fast-forward a few years. It’s the middle to late ’90s and I have changed direction somewhat. Actually, I wasn’t searching for anything at the time, least of all something ‘witchy’, but I came across an essay on the history of Wicca by Julia Day. She made several rather slighting remarks about a man called Robert Cochrane and referred to some letters he wrote to Joe Wilson and some strange business about a secret name of the Goddess that was somehow connected to the number 1734. That night I dreamed that I was on a dark hillside and Robert Cochrane was there with me, trying to tell me the secret name of the Goddess. The next day I was slightly fazed by this at first, but then forgot about it until that night when I had the same dream, but this time he communicated a Name. I prefer not to say what it was, as it still seems private to me, but I can state categorically that it was not a name that would be recognized as the end of a search for that name by the 1734 method!

Anyway, this led me to do some searching online, remember there was much, much less available then, and I came across a practitioner of 1734 in the States, Sandy Kopf, and her husband Doug. She in turn put me in touch with Joe, who was running something called Metista. Most people assumed that Joe no longer had any interest or connection with 1734 by then, although Joe showed how Metista came from the same spiritual root, which was to find your own expression of spirituality, personally and culturally, rather than just scavenge the scraps of other systems. Anyway, I found myself drawn in; I found his ideas fascinating and relevant, not least because he was demanding a critical attitude towards our spiritual understanding, a practical way more than anything, rather than a faith-based one.

Joe himself was quite a character, he had been through most things, including heavy drinking and womanizing, he had been a very heavy smoker, which had left him with COPD. He’d suffered from episodes of crippling depression (there were several attempts at suicide in his youth) and no doubt all these things had affected his reputation in various ways, as well as his ability to sustain an effort to fruition. However, Joe in the late 90s was, in many ways, a wise man. His wisdom was hard-won and the result of coming to terms with his many faults and, in some cases, working with them, making them sources of strength. He was funny, irreverent and utterly dedicated to expressing his path for the benefit of others, he did really think there was something very important in what he was doing.

Metista was based upon the idea of finding your own spirituality, not endlessly borrowing, or stealing from other systems. He took on and developed the idea of cultural appropriation, which has now become a popular, and much misunderstood, catchphrase among the very people he was criticizing back then, the new-age, eclectic wannabees. So there’s this idea that your starting point, your real starting point, might be just to stand there and listen, listen to whatever is there, the wind, the water, birds, and to your own heart. Joe also suggested culturally neutral or generic forms of ritual as a starting point, rather than grabbing at Native American or whatever practices, torn out of context, in order to find one’s own way and to one’s own cultural roots. He made the point that being part Native American doesn’t give one automatic rights over tribal practices that might be very much the property of that people.

At the same time, he was not a cultural purist; he understood that the average American is very much a ‘Mutt’, that complex and mixed cultural heritages are present, and not just in Americans. He researched his own ancestry and found it extremely mixed. Also, his last wife was African-American and a practitioner of Hoodoo, which he was very enthusiastic about and recommended it to me as the nearest to the sort of folk magic he learned as a young man.

The Metista group eventually broke down and a number of us became the core of Toteg Tribe, the final expression of Joe’s philosophy. It is both simpler and more complex than Metista. The name comes from Joe’s group in the 70s and 80s, Temple Of The Elder Gods – TOTEG for short, which seems to have morphed from a 1734 type practice to something based on Native American spirituality. We have to remember that Joe’s insistence on not taking from other traditions willy nilly, and not practicing cultural theft was, in a real sense, trying to make good on his own past where he pillaged most of everything! So Toteg Tribe was, like Metista an attempt at making some kind of restitution. The various clans of the Tribe are free to go different ways, develop their own praxes, in line with the overall Toteg Tribe philosophy.

While all this was going on, Joe was quietly teaching a few people, myself included, the essence of 1734. Many thought he’d abandoned 1734, but it was still close to his heart and he was able to impart something, but it was very different to what he’d done in the 70s, which had a particular ritual format. Now, when I say he was teaching, I have to explain he was not giving lessons as such, but rather provoking us to learn, and that learning was not by rote, but rather a matter of helping us with our own investigations. Later, it became obvious that Joe taught different things to different people. Also, when he often replied to a question “I haven’t the faintest idea!” he sometimes had a very good idea – he knew a lot more than he let on!

BTPM: How did you come inherit some of the Virtue of 1734 and can you explain a little about what that means?

SI: It’s an odd little story and not entirely straightforward. I was not made the Virtue-holder for all of 1734, the way Shani (Oates) was for the Clan of Tubal Cain, for instance. Joe knew he only had a short time left and, in creating Toteg Tribe, he also appointed a number of people as ‘Doyens’, elder of the tribe, and one day a certificate arrived in the post, declaring me one of the Doyens! I’d never had such a certificate before, but it allows me to perform weddings and funerals within the Toteg Tribe tradition.

To be absolutely clear, this is not the passing of the 1734 Virtue! I mention it as something comparatively official, documented and exoteric, while what Joe did about 1734 was quite different. He had already declared that nobody could be in charge of 1734, and attempts to be more 1734 than thou were, if anything, proof that one was not 1734 at all. He regarded it as being too diffuse a phenomenon to be simply regarded as a tradition that anybody could be in charge of. At the same time, he was concerned that his own stream within the broader 1734 family could be lost, diluted, falsified, so he asked three people, Aisling, Kaerwyn and myself, to act as ‘Guardians’- really to explain what 1734 is in essence and to defend it against falsification. It is sometimes hard work as people often don’t even bother to read up on 1734 before making pretty baseless and either ignorant or malicious statements about it, there’s a good number of such things on the internet.

So, I have never regarded my appointment as a Guardian of 1734 as any kind of final authority, I was one of a small number of people who ‘got it’ and to whom was passed a little gift of spirit. Think of it like the leavening in bread or a little dollop of yoghurt culture that you have to add to the right ingredients to make your own bread or yoghurt. That enabled me to eventually found the Clan of the Entangled Thicket and become its first Magister.

BTPM: There has been a great deal of misunderstanding and assumption regarding 1734 and its relationship to Witchcraft and Wicca. Getting to the meat of the matter, and as a guardian of the tradition, can you summarise what 1734 is, what it means and how it relates to witchcraft?

SI: Certainly; the essence of 1734 is a Mystery Tradition in three modes. The first is 1734 as a method, simply using the methods of poetic induction to gain insight. Secondly, as a system, to work with it systematically, to develop one’s own path from that. This is very difficult, but possible to do without a teacher. Normally one needs at least a mentor to help or inform one; else the siren call of the Lapwing too easily misleads us. Thirdly, actually as a tradition, we can’t really say it is an initiatory tradition in the conventional sense, but it contains several clans and covens that are free-standing traditions within the 1734 fold.

As to how it relates to witchcraft, that very much depends on one’s definition of witchcraft. It is essentially different to Wicca for instance, it has a mystical dimension lacking in mere ‘kitchen witchery’. I’m not too bothered if somebody wants to deny it as being witchcraft, as it is certainly a mystical and poetic Craft of great potency.

BTPM: What would you say are the core philosophies and/or practices which determine 1734 method?

SI: I tried to put this in a nutshell once, and came up with “Poetic induction into the Mysteries and entry into the Dimension of Silence.” I think that still stands, but it does require a bit of explanation. That first part, everybody knows that the seeds were sown through Joe Wilson’s correspondence with ‘Robert Cochrane’ – Roy Bowers, the founding magister of the Clan of Tubal Cain. Joe used the Letters as examples, this has sometimes led to misunderstandings. I remember somebody saying rather dismissively “Six letters isn’t much of a tradition”! And they’d be right if that’s all 1734 was, but you have to get it into your head that the “Cochrane Letters” don’t constitute a grimoire or Book of Shadows, they are not a big secret, but a series of letters written to a near stranger. They represent a way of looking, seeing and thinking, and once read away from their original context, they allow a way into that mode of being, which is essentially poetic. Now, by poetic I mean ‘poesis’ which is the heart of all creativity, rather than writing verse.

BTPM: Can you clarify the significance of the Robert Cochrane letters with regard to 1734?

SI: Yes, they are indeed an essential part of 1734, and anybody who is serious about 1734 would be required to attempt to solve at least some of the riddles, questions and symbols in the Letters, but it has to be realised that our answers might not be the same as each other’s and might differ from how they’d be understood in the Clan of Tubal Cain. Most of these are not, shall we say, objectively true, nor merely a wholly subjective insight. Roy Bowers was using The White Goddess extensively in his letters to Joe, and that’s a notoriously unreliable book! After a session with it, Jane and I usually refer to Graves as “Mad Bob” – the rate he makes up stuff is extraordinary! So you are not going to that source for objective facts, but it has a way of thinking, of making connections, that is poetic and magical and it is a kind of initiation into that mindset. However, it requires one more element: discrimination. Otherwise we spend our entire lives running after the trickster Lapwing, englamoured, and mistaking the pretty things on the way for genuine insight. We need the poetic vision, but also a reality check.

BTPM: Can anybody claim to be 1734, or is it an initiatory tradition alone?

SI: I’m very aware that you wrote this question before I wrote a previous section, above, which goes some way to explain this! But it is worth restating and clarifying. Anybody who does the work and gains the insights can claim to be working 1734, I don’t think they should get too hung up on whether they are ‘real 1734’ – Joe was dismissive of people’s trying to be ‘more 1734 than thou’. 1734, taken as a whole, is quite a mixed bag, but within it there are traditions that go back a fairly long way and have their distinctive way of working. My own clan, The Clan of the Entangled Thicket, is a baby by comparison, but seems to be maturing nicely. Remember that, for a tradition to be a tradition, it has to be handed on; otherwise maybe you are working the 1734 system, which is no bad thing.

BTPM: In what way did Joe’s mentors ‘Sean’ and Ruth Wynn Owen influence 1734?

SI: Well, Sean was the person who first brought Joe to this vision. It fitted very well with what Roy taught him. It’s interesting that Sean actually kept the original of the first ‘Cochrane Letter’ to Joe. Joe thought it had been destroyed, and it was only a very few years back that we discovered a cache of things Joe had sent to Sean, they’d been kept and were sent to one of us by Sean’s widow. I had a brief, but fascinating correspondence with her, and found that her recollection of Sean was very similar to Joe’s. So Sean contributed a fascination both with The White Goddess and things Celtic, a load of family lore, that probably included some of the folk magic he practiced, and a spiritual stance gained from his friendship with Native Americans.

Ruth provided both a sharper focus for that Celtic lore and a firmer grasp of ritual, especially as it could be applied to the seasons. She also contributed to the ethos of 1734, when I read some of her aphorisms I recognized exactly what Joe was about in them. I’d love to know more about her, but what is available is somewhat limited.

BTPM: You have studied with two of the most influential teachers and founders of traditions in modern witchcraft and Wicca. In what way do they differ and how, if at all, are they similar?

SI: Alex and Joe were simultaneously very different and in some ways quite similar. They both had something of the rascal about them, which was both a good thing as it did away with pomposity and a rather darker thing in some ways. Alex’s love of publicity could very much obscure the serious attitude he had towards magic, he really lived magic. As did Joe, but in a different way, he was far less ritualistic about it. Because Alexandrian Wicca and 1734 were such different things it can be difficult to compare them directly, but both had an openness of approach to teaching magic, a depth of knowledge that many failed to spot, and both are coming to a point where they are being reassessed by new generations of witches and magicians.

BTPM: Finally, how do you remember Alex Sanders and Joe Wilson and how do they continue to make their presence known to you?

SI: In both cases, I remember them fondly and respectfully. I rather lost faith in Alex at one point and felt he’d lost his way a bit, something confirmed by Maxine (ed. Sanders), but he was still more of a consummate magician than many of his critics in those difficult last years. With Joe it was very different, as I was talking to him on the phone two or three times a week for four years (after an initial period when our discussions were entirely by email) so, although I got to know him reasonably well, so that I thought of him as both teacher and close friend, paradoxically, I never met him in the flesh. I last spoke to Joe a couple of days before he died, in Alex’s case, I’d been out of touch for a long time and renewed contact shortly before his death, but he died before I could visit him.

Both seem very present in my life and at each Hallows they are both remembered. In different ways they are a part of what I am, and sometimes my work seems like a dialogue with them. This has sometimes been a surprise to me with Alex, as my path emerges from my time studying with Joe. But while 1734 is so different to anything taught by Alex, I’d never have got there without his teaching and inspiration. I remain grateful for having known him. My debt to Joe is slightly different as he pushed me towards teaching and being ‘out there’ and being willing to lead rather than just being a follower, but he reshaped my idea of spirituality and of magic as well, so what I am, the best of me, I owe in part to both of them.

BTPM: Thank you for taking the time to be a part of this interview.

SI: Thank you, it has been fascinating for me to undergo such a reassessment. It’s also been hard work!