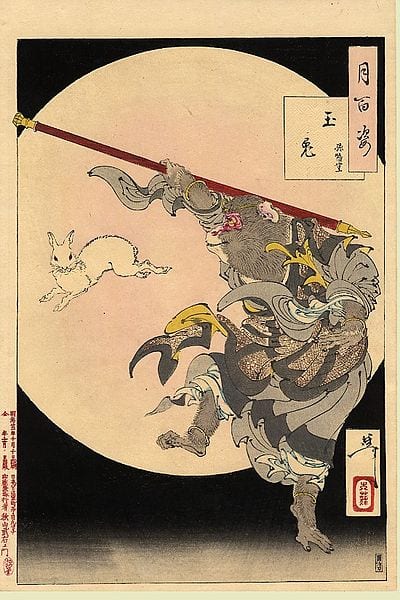

Let me tell you a story… a story of a being somewhere between angel and demon, whose pride aspired to the highest heavens and whose home is the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit, a rebellious King who warred with Heaven and stole the Wine of the Immortals, sharing it with mortals.

There was a rock that since the creation of the world had been worked upon by the pure essences of Heaven and the fine savours of Earth, the vigour of sunshine and the grace of moonlight, till at last it became magically pregnant and one day split open, giving birth to a stone egg, about as big as a playing ball. Fructified by the wind it developed into a stone monkey, complete with every organ and limb. At once this monkey learned to climb and run; but its first act was to make a bow towards each of the four quarters. As it did so, a steely light darted from this monkey’s eyes and flashed as far as the Palace of the Pole Star. This shaft of light astonished the Jade Emperor as he sat in the Cloud Palace of the Golden Gates, in the Treasure Hall of the Holy Mists, surrounded by his fairy Ministers. Seeing this strange light flashing, he ordered Thousand-league Eye and Down-the-wind Ears to open the gate of the Southern Heaven and look out… presently they were able to report, ‘This steely light comes from the… Mountain of Flowers and Fruit. On this mountain is a magic rock, which gave birth to an egg. This egg changed into a stone monkey, and when he made his bow to the four quarters a steely light flashed from his eyes with a beam that reached the Palace of the Pole Star. But now he is taking a drink, and the light is growing dim.’

Ch’êng-ên, Wu. Monkey (Classics) (p. 11). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

In the Chinese classic 16th Century novel Journey to the West, also known by the title of Arthur Waley’s translation Monkey, Wu Ch’êng-ên blends elements of folklore, fable and fairytale with the three great Chinese philosophical traditions of Taoism, Buddhism and Confucianism. Using allegory, the story of Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, follows Monkey as the “…restless instability of genius…” (Arthur Waley). This genius, the relentless aspiration of Monkey, sees our protagonist rise to reach the heights of Heaven beyond the North Star, and his subsequent rebellion. Seen at the time as a reflection of earthly bureaucratic governance, the hierarchy of the celestial palace follows and balances the dynamic of the terrestrial realm, with fairy ministers and Immortals. Having excelled and attained to the position of King and Patriarch over his earthly domain, Monkey conceives of no reason why he should allow destiny, an ordering power of the Immortals, to prevent him from achieving the highest throne in Heaven.

‘Born of sky and earth, Immortal magically fused, From the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit an old monkey am I. In the cave of the Water-curtain I ply my home-trade; I found a friend and master, who taught me the Great Secret. I made myself perfect in many arts of Immortality, I learned transformations without bound or end. I tired of the narrow scope afforded by the world of man, Nothing could content me but to live in the Green Jade Heaven. Why should Heaven’s halls have always one master? In earthly dynasties king succeeds king. The strong to the stronger must yield precedence and place, Hero is he alone who vies with powers supreme.’

Ch’êng-ên, Wu. Monkey (Classics) (p. 74). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

After reaching the Northern Heavens, Monkey is ridiculed and is put in the stables to care for the horses. Irate at the insult, he returns to the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit (Earth) and is immediately in receipt of tribute from two one-horned demon kings who are appointed in the vanguard of Monkey’s army. He requires this army of demons, over whom he is King, as the armies of Heaven are arrived to arrest Monkey, who has styled himself “Equal to Heaven”. After defeating all challenges, Monkey is granted the rank of “Equal to Heaven” and returns to Heaven until, drunkenly, he consumes the elixir of the great alchemical sage Lao Tzu, mythic founder of Taoism, and steals the Wine of Heaven for his mortal subjects. Furious, the assembly of the Heavens gather to capture Monkey.

…the Kings of the Four Quarters… the twenty-eight Lunar Mansions, the Nine Planets, the Twelve Hours, and all the Stars, together with a hundred thousand heavenly soldiers… draw a cordon round the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit, so that Monkey should have no escape.

Ch’êng-ên, Wu. Monkey (Classics) (p. 59). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

After a long series of challenges and battles, Monkey is eventually captured but killing him proves impossible. Recognising the threat Monkey poses, having ceaselessly gained a series of boons, magical powers and objects, including ‘illumination’ or ‘enlightenment’, the Jade Emperor (God) sends to the Buddha for help in restraining the seemingly limitless capacity for this genius to achieve. Tricked by the Buddha, Monkey is imprisoned beneath a mountain.

If this story sounds familiar, it is not surprising. From Prometheus to Odin, we see in Monkey the archetypical trickster god of enlightenment, evolution, the “… restless insatiability of genius…”. In many respects, this story shares with the western mythology of Lucifer, or the fallen and rebellious angels who war with Heaven, as well as those Nephilim who have congress with the Daughters of Men. There is no mistaking a commonality in the folkloric and mythic threads that run throughout the story, with its one difference in that Monkey is not cast as the enemy. Indeed, the allegorical nature of the stories of the Monkey King, Sun Wukong (‘Monkey Awakened to Emptiness’) reveal, perhaps, the hidden depths of the shared myths.

Monkey, in many respects, is symbolic in the East of the mind itself, and the story of Wukong demonstrates the evolution of such in its narrative. Indeed, it is significant that all of Monkey’s magic is attained through the Taoism of his masters, and it is the Buddha nature which finally brings the mind under calm influence (note, not control). The mind, like Wukong, contains limitless capacity for conquering some of life’s most contentious challenges, and at the same time may become prideful and drunk and assume supremacy. The lessons of the Monkey King speak of sovereignty.

Since ancient times, people have likened the mind to a monkey because they truly saw that when the mind is wild and foolish this a tremendous obstacle on the way. If learners can control their mind then the Tao of essence and life can be comprehended.

Liu Yiming (18th c. Taoist master)

Sometimes, we may find inspiration and understanding from unexpected and unlikely sources. The legend of Sun Wukong is summarised here with the hope and intention that there are some few out there who might read it and realise something unique and important to them. Hidden within the magnificent collection of Chinese folktale, mythology, oral tradition, religion and philosophy is a kernel which might be that spark that can bring illumination and Monkey may well share with you, dear reader, a dram of the Wine of Heaven enough to make you drunk.