First published in The Hedgewytch, February/Imbol 2013

When the Michaelmas moon was come in with the warnings of winter, Sir Gawain bethought him full oft of his perilous journey. Yet till All Hallows Day he lingered with Arthur, and on that day they made a great feast for the hero’s sake, with much revel and richness of the Round Table

Gawain and the Green Knight, anon.

Pilgrim: Latin peregrinus, ‘beyond country’, coming from afar.

Peregrinatio: Medieval romantic motif using worldly metaphor for spiritual progress.[1]

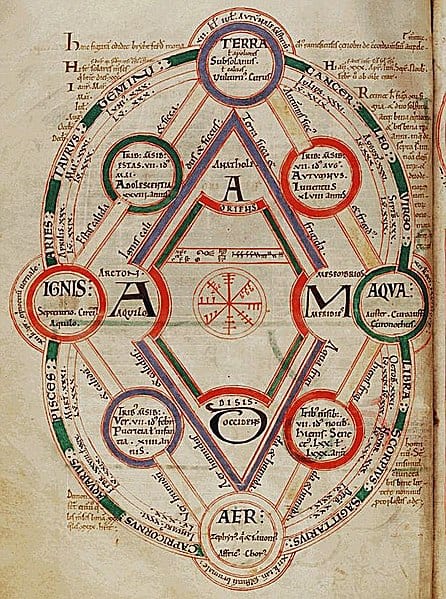

After the glorious summer, “…when Zephyr breathes lightly on seems and herbs…” [2] the cold North wind heralds the solemnity of change as the Saturnine season approaches Arthur’s court. At the feast of All Hallows, the congregation of covenanted knights gathered in their round, made feast and revelry with their Lord Artur. the gathering was sombre, we are told, as Gawain, the grail questing knight, infused with medieval Gnosticism of the Languedoc, spoke to Arthur, his uncle: “Leige lord of my life, leave from you I crave. Ye know well how the matter stands without more words, tomorrow am I bound to set forth in search of the Green Knight.” [3]

Thus commences the journey of our hero, departing as a pilgrim to the Green Chapel (perennially verdant in contrast to the Wasteland that is winter) and dedicated to the quest, committed to fulfilling the promise of the old year – seemingly self-possessed and composed to face the journey before him, destined to lose his head.

This medieval, anonymous poem, a favoured festive tale, outlines the trials of Gawain as he enjoins in a year long voyage to duel with his adversary, the fantastical giant of the Green Chapel. Forging his path upon the seasonal journey, Gawain embarks upon a journey that will end, ultimately, and in his own understanding, his beheading. Temptation besets his smooth passage as the peregrinus, protected by the five points of the pentangle or pentagram, which symbolise the hero’s virtues, bids farewell to his loved ones, his home of kith and kin, leaving behind the mundane world he has known, cared for and protected him in search of fulfilling the promise to the Green Knight; a promise which is a sacred oath in service to his Lord, a journey he must make alone and which will conclude with the loss of the head. For no small purpose does the poet dwell upon all that Gawain must leave behind him, the “…solace of soft summer…” and the comfort of court. Here, we are reminded of what the pilgrim sacrifices in undertaking this pilgrimage to the Green Chapel, those things which cannot be his shield or council during the most demanding part of the quest.

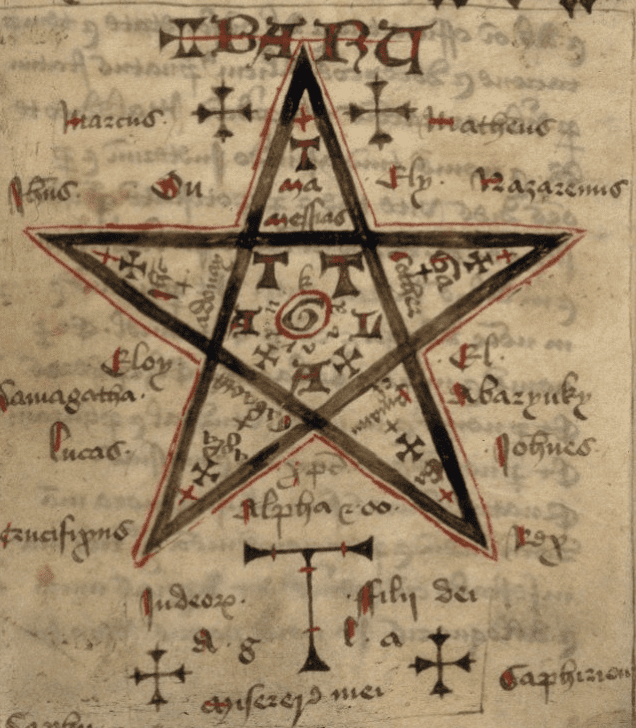

During the preamble to Gawain’s departure, the poet curiously provides us with some discourse upon the symbol by which Gawain places his faith upon his journey of Self and the Green Chapel. This “…symbol of Solomon set ere-while, as betokening truth…”. The pentangle, we are informed, is significant to Gawain as representing an ‘endless knot’, whilst its fivefold nature express his virtue and faith. Such a motif would have been readily identifiable in the medieval mind as correlating with the wounds of Christ, and students of modern Traditional Witchcraft might also be reminded of the five knots and the ‘Round of Life’ expressed by the late magister of the Clan of Tubal Cain, Robert Cochrane [4]. It is, perhaps, interesting to note that the five stages of the Round of Life, when looked upon the ‘endless knot’, suggest the returning soul moving through each stage of incarnation. Paralleling the cycle of the compass knots of five (plus three, as Evan John Jones and Shani Oates observed), the Gawain poet echoes similar themes through detailed expressions of the movement of seasons.

And all these, five-fold, were linked one in the other, so that they had no end, and were fixed on five points that never failed, neither at any side were they joined or sundered, nor could ye find beginning or end. And therefore was on his shield was the knot shapen…

Gawain and the Green Knight, anon.

Now, with particular reference to the passage of seasons and the ‘Round of Life’ upon the Compass, we can see here the symbolism of the journey as being both upon the physical and metaphysical, both occurring as an actual venturing forth from the safety of the mundane, the trappings which support the superficial ego, as well as the greater pilgrimage through a single incarnation upon the manifest plane from birth to death. Gawain’s own pilgrimage is made the more poignant by the ominous fact that the destination for him will likely result in his physical death, although the ‘beheading game’ is a traditional wisdom revelation motif. In this type of story, the wisdom bursts forth from or replaces the hero’s head, as Athena emerging form the cranium of Zeus, superimposing the mundane and profane with the profound, reborn wisdom of the sublimated ego. Thus, the spiritually beheaded dies to the world and sees the Wasteland become the Chapel Perilous. Connections between the Gawain poem and older pagan rituals and themes are rife, most particularly Briciu’s Feast (Fled Bricrenn).

When we think of a pilgrim, we are reminded of medieval folk who left their homes on a spiritual journey, often toward a shrine, Cathedral, or other site of significance, joining with others, perhaps, upon a well trodden path. Some pilgrimages were offered to particular people or saints, such as Thomas Beckett, or to receive a boon, as the healing waters of Lourdes, France, while visions and holy relics drew many travellers. Farther afield, perhaps the greatest pilgrimage in the Christian world medieval world was the quest for Jerusalem, and undertaking such a spiritual journey promised a true cleansing of the soul and washing away of sins, a return to source, a spiritual homecoming in metaphysical terms (Medieval Jerusalem becoming a World Centre, axis mundi, as spiritual navel). Such was the case for the Templar knight William Marshall (1146 – 1219) as well as Robert the Bruce (1274 – 1329) whose last request was that his heart be taken on Crusade to Jerusalem.

In ancient times too, common folk and kings alike made pilgrimage to sacred sites to receive oracular pronouncements and the temple complex at Delphi attracted visitors far and wide who left their hearth with the express purpose of discovery; the principle temple of Apollo famously bearing among its three maxims, the imperative to: Know thy self.

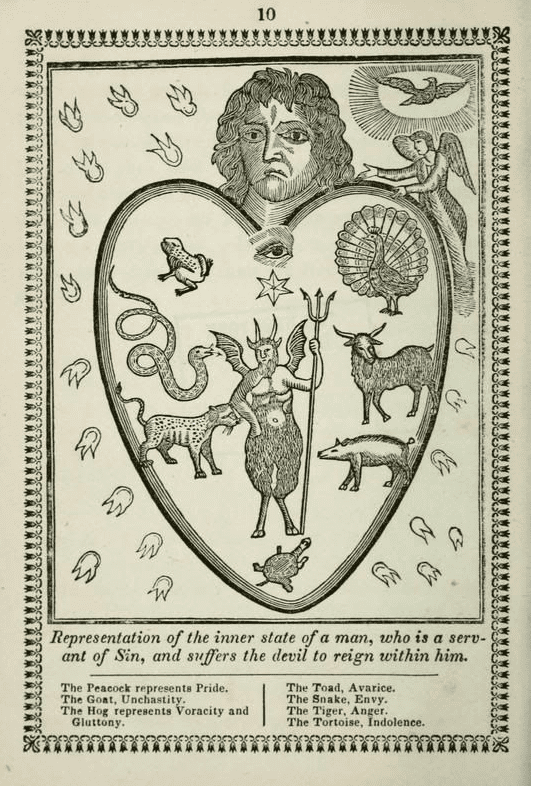

The motif of the piglrim, peregrinatio, is a recurring theme in medieval prose romance, including the other anonymous and somewhat Gnostic 14th Century poem, Pearl; which is sometimes accredited to the same author as Gawain. Other literary examples include most obviously Chaucer, Danté and Bunyan. the allegorical symbolism of the peregrinatio brings awareness of the trials of everyone’s journey through life and transition from worldly to spiritual awareness, a movement from transgression to transcendence. Temptation often comes in the form of the flesh, trappings of worldly desire and frequently within the underlying Christianised prose it is the province of the Devil as adversary (literally ‘turned toward’) and the tempter [6]. The hero in medieval works that incorporated the peregrinatio, or pilgrimage, as its foundation theme often emphasised the preference given to three cardinal virtues and the attainment and understanding of Faith, Hope, and Charity. There is a ritualistic element to some such tales. Here, it is to be remembered that the story is allegorical and the inevitable confession of the hero is more truly an acknowledgement of his transgressions upon the path and reconciliation within the Self. Gawain, in the end, is his own harshest judge. There is, in the pilgrim, a movemement from a naivety and immaturity through to maturation, wisdom and the possibility of death, each knot within the five staged Round of Life.

The underlying objective of any pilgrimage is to undertake a journey in order to achieve some spiritual or mystic purpose. In the instance of Gawain, it is the fulfilment of a promise committing him to his destiny, under the unseen hand of Morgaine le Fey as harbinger of Fate. The poetic theme here is indicative of our own journey teaching us that we can commit to fulfilling the Round of Life with awareness of Fate, Herself the very author, present at every turn, concealed until the revelatory moment. The path and trials define, determine and forge the journeyman, as important as the actual destination itself. Indeed, the path is in many ways the destination revealed, it is in the five knots, or virtues of Gawain, that it is defined. As the pentangle, the ‘endless knot’ becomes a symbol of infinity, with the addition of three further knots completing the ouroboros serpent, twisted in a figure eight, devouring its own tail.

The purpose of the pilgrimage is relevant to cultures across the world and spanning time. Some Native Amerindians used pilgrimage as an individual journey, undertaken alone, as a part of a rite of passage, culminating in a vision which they will take back to the tribe or clan. Ultimately, the basis of pilgrimage as a rite of passage is that it is performed without accompaniment or support from the trappings of the ego; it is a voyage away from the profane and mundane. Here, then, the pilgrim is tested along the way in a battle of wits and virtue with the Self as arbiter. Here, we encounter the Adversary, disguised as inertia, doubt, guilt, self-pity, and loathing, our only solace to be found in, and the overcoming of, Fate. Gawain’s temptation is that of the flesh, analogous with desire as opposed to necessity [7], symbolic of physical and carnal desire, later fear of dying, clothing a more subtle message concerned with the wants of the ego self.

Peregrinari pro Christ (Pilgrims for Christ), as called White Martyrs, refer to those few, especially in Celtic Christianity, who undertook a world pilgrimage, following an ascetic life and trusting in Providence to provide for all their worldly needs while steering their journey, with no fixed or preconceived physical destination. Rather, a spiritual position becomes the locus of the pilgrims’ progress.

At the end of Gawain’s pilgrimage, he arrives at the Green Chapel and faces his Fate at the hands of the Green Knight, that verdant giant of nature. But, standing at the hinge of the year, he receives three symbolic strikes and finds that none is fatal. Instead, it transpires that the Green Knight is neither the adversary, as expected, nor the Devil. In actuality, Fate in the guise of Morgaine le Fey, is the force behind both the entire game and each of Gawain’s preceding trials, and the struggle was not, in fact, with the Green Knight but his own moral compass. In the end, it was the Devil he knew that was his tormentor, struggling with his self and his own fears. This was Gawain’s greatest challenge upon the journey and by which he was tested – his own actions informing whether or not he lost his head.

As in the monmouth outlined expertly by Joseph Campbell (1904 – 1987), the return to the normal world sees the hero re-emerge fro the dark cavernous winter with the boon. Through his journey, moving ever toward the fateful duel, the hero is changed, returning to the mundane, allegorically defined as Arthur’s Court (the mythological panoply of stars governed by the Great Bear, Arthur ,and his zodiacal Round Table), shaped, moulded and transformed, renewed, and reborn.

Occasionally, we may take repose upon our own journey to allow the effects to filter through, a profound pause after peregrination during which time the alchemical distillation settles into clear waters once more. The path we tread may, at times, seem fraught and crooked, yet clarity comes when we, once again, as the pilgrim, fully adept that the way can be made, in fact, straight and true.

- Berger, Sidney E. Gawain’s Departure from Peregrinatio

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, anonymous, trans. Jessie Weston

- ibid.

- Described in the Robert Cochrane Letters.

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, anonymous, trans. Jessie Weston.

- For more on the Adversary, the Book of Job clearly demonstrates the ‘Satan’ as a high angel of Yahweh and the agent through which Faith is measured on God’s behalf.

- Recall Robert Cochrane’s Witch Law