A Brief History of Free Will in Witchcraft

The Italian Basilica at Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, is home to some remarkable Byzantine art depicting various scenes of Christian tradition. Dating to the 6th Century, one mosaic depicts a scene from Matthew 25:31–46, ‘Christ separates the sheep from the goats’. Either side of the Christ figure are seated two angels, one on the right-hand, ‘dextral‘, coloured radiant blue while the angel on the left, or ‘sinister‘, is distinct in bright red. This is sometimes thought to be among the earliest extant depictions of the angel who would become, through the Middle Ages, the Devil.

“Maximus Confessor (580 – 662 CE)… argued that… The Devil’s being is good; his evil results from an ignorant misuse of Free Will… We sin of our own Free Will…”

Lucifer, The Devil in the Middle Ages, JB Russell, p.36

Modern witchcraft, following the speculative work of anthropologist and folklorist Margaret Murray, often equates a sympathetic notion of the Devil with pre-Christian, or folkloric pagan, concepts of God. The idea that the devil is a demonised pagan deity, or amalgam of pagan ideas, manifesting as a recurrent and suppressed religion linking to antiquity, has been seen to be questionable, and yet it persists in Neopaganism.

The question of the principle agent of evil goes hand in hand with the problem of evil itself. This can only be approached from the perspective of the Christian worldview from which our culture finds its foundations. The early theologians and philosophers, such as Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (5th – 6th C), examined through a distinct and theurgical approach to understanding deity, influenced principally by Neoplatonism and, perhaps, Gnosticism , through emanations from the One, the Good. This proposes a transcendent and immanent God who is omnipotent and omnipresent. That is, all is from God, being the realisation of the Good, and all is a part of God. Furthermore, all things yearn to reunite with its origin and finds desire in God.

This is a very rough synopsis, but it is necessary as it leads to the inevitable question of evil: if all is an emanation of God, created by and contained within the ever-present realisation of God, why do bad things happen in the world?

For those early Christian theologians, we find the defining of evil was a difficult conundrum and thinkers such as Dionysius obviously didn’t prefer either of the two obvious conclusions: either God was not all powerful and all knowing, or alternatively we allow for a Dualism as found in Zoroastrianism. Instead, one solution is that evil is the absence of Good, it is the barren land where God is lacking, the void, non-being.

One of the more prevalent solutions to the problem of evil is resolved with explanation of misuse of Free Will, which is present within the Fall of both Man and Devil. This ‘Augustinian theodicy’ has its origin with Augustine of Hippo (AD 354–430), was further considered by Thomas Aquinas (AD 1225 – 1274), and was most recently reworked in the 20th Century by Alvin Plantinga in his 1977 work God, Freedom, and Evil. In his lifetime, Augustine had his theodicy challenged in public debate by a Manichaean called Fortunatus. Fortunatus argued that Augustine’s solution of Free Will does not let God off the hook for evil as it was God, in Christian doctrine, who gave mankind Free Will. Wherever you stand on this, the fact remains that freedom of the individual Will is implicated, and the ability to discern and choose is the key. This, however, does not necessarily lead us to evil, as we shall hopefully demonstrate.

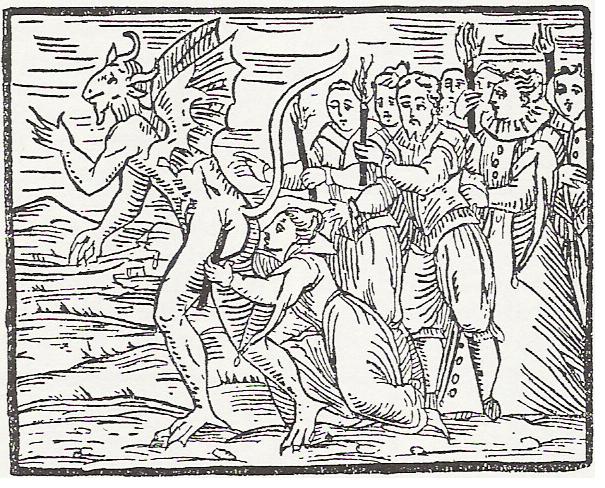

In the diabolism of the witchcraft trials, a common feature is the invitation by the Devil to renounce God and sometimes be baptised anew. This demonstration of Free Will was seen as evil in electing to exercise the will and not follow faith in God. Here we have a curious thing in that using Free Will to follow the edicts of faith, the demonstration of a nature desirous of God, means fulfilling societal expectations and cultural conditioning. This blindly following the herd, looks very much like NOT exercising will at all. Thus, by choosing to follow God, we acquiesce to relinquish that freedom to choose the other. Conversely, renouncing this path may be to begin the disentanglement from cultural conditioning and truly exercise Free Will.

To illustrate the point being made, here is an allegory to try to help elucidate this difficult idea. Imagine you are in a single room, no larger than a single cell, with solid walls on all sides and a high ceiling. There is a single door to the room. You don’t know whether the door is locked or may be opened because you’ve never tried to leave. To use Free Will as per cultural conditioning is to ‘choose’ to remain in ignorance of whether you are a prisoner or are free to leave at any time. The paradox in choosing to stay is that you can never know whether you actually do have Free Will, or whether it is an illusion only. In this allegory, it would appear that the person in the room is a prisoner of the idea that they are free and only exercising Free Will can remove the state of ignorance. That is, only by choosing to try to leave can we attain the knowledge of our situation and understand that our fate is not determined under the illusion of Free Will.

If myths are the stories we tell ourselves to give meaning and purpose to life, the overarching narrative of our society has been that if Christianity. The entire corpus of our cultural conditioning is embodied within a worldview that finds its place in relation to the Christian myth. We find many folk tales which incorporate, by necessity, Christian elements because they are subject to the cultural model, or skeleton, upon which others rest. Rather than being purposefully Christianised, medieval myth rather retains its structure in this perspective and, therefore, the Devil of the witches is most assuredly that of Christian nature.

(In a brief interlude, I note with amusement that what has just been said will be taken as rank heresy to Neopagans and modern witches, further demonstrating that the cultural model exists today in new attire.)

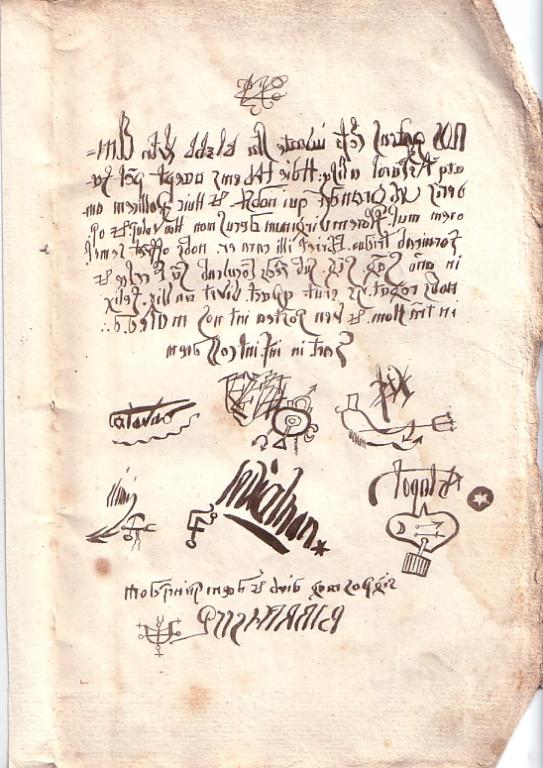

The role of the Devil in the early Medieval period incorporated mostly a capacity similar to, and reflecting, early Christian and late Jewish ideas of the ‘Adversary’. In Old Testament literature, Satan had been an active agent of God, most obviously in the Book of Job. Here, his function is to test the faith of Job as per God’s bidding. However, as the church matured and scholasticism increased, and a rich tradition of literature blossomed, demonology progressed and the Devil’s image shifted too. The grimoires similarly experienced a high at this time, incorporating the Goetic and Solomonic traditions, expanding out of Byzantium, Arabia, Classical & Neoplatonic theurgy and folk Necromancy. Within the prevailing worldview, the Devil became confirmed as having dominion over the Underworld, while the rumoured book of Enoch speculated as to His role in the rebellion against God with the Fallen Angels.

The medieval mind was aware that the Devil originates when people (or angels) exercise their god-given Free Will, with preference for that which is not of the Good (God). We have discussed previously Lucifer’s role as rebel, but it is worth reiterating here the function as champion of Free Will. The paradox of Free Will is that of Neo in The Matrix, who may choose one pill and experience, with knowing, the Matrix. The alternative is to continue never quite sure if it was ever really a choice at all! They say the greatest trick the devil pulled was to convince man of his nonexistence. If this is so, then surely God’s great trick is to convince man they have Free Will so long as it’s never exercised.

Heresy (n): “doctrine or opinion at variance with established standards”… from Greek hairesis “a taking or choosing for oneself, a choice, a means of taking; a deliberate plan, purpose. (Etymonline.com)

Paul Huson’s excellent Mastering Witchcraft contains in its beginning a rendition of the Lord’s Prayer written backwards. Together with the instructions to repeat the same, we see an act of moving away from the centuries of bondage to the machinations of the church structure, which has exerted its absolute power throughout Europe and coloured the cultural idioms which are the underbelly of our modern world. So ingrained is it that, at first, such an idea might feel physically abhorrent and frightening to the practitioner. If you can bring yourself to try it, however, you may find the choice to be a powerful spell to break the illusion. We are also told that this was one of the acts required in the initiation of the traditional medieval witch.

Endnote: Returning to The Parable of the Sheep and the Goats, Matthew 25:31, it is pertinent to observe that sheep are a metaphor for docile followers, content to be led even to their death. Meanwhile, the goat represents strong will and independent thought, inquisitive nature, even capriciousness (from the Latin Capricornus, meaning “horned like a goat”). The goat became the cultural icon of the Devil, therefore, while ‘sheep’ is colloquial for mindless following.

Postscript: I penned this piece several years long since, and it is not necessarily and entirely congruent with my current apprehension of the topic of free will. I share it here as a reflective piece upon an hoary (and thorny) subject which continues to perplex the best minds of today, although the arguments have barely advanced since early Greek philosophers tangled the subject. As witches within my tradition, the nature of Fate and the role of the devil is pertinent.